In 1663, 122 years before legendary naturalist John Audubon was even born, Englishman John Josselyn sailed from London to Maine to stay with his brother in “Scarborow, or Black-Point.”

“The Country generally is Rocky and Mountainous, and extremely overgrown with wood,” Josselyn wrote of the territory that would become Maine and New Hampshire, “yet here and there beautified with large rich Valleys, wherein are Lakes ten, twenty, yea sixty miles in compass, out of which our great Rivers have their Beginnings.”

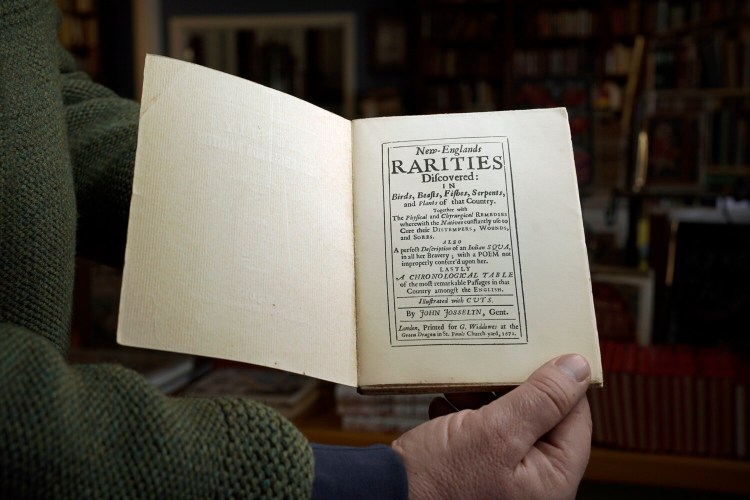

Josselyn lived in Scarborough for eight years, exploring New England to observe and catalogue native flora and fauna. An amateur naturalist, though highly enthusiastic, he compiled his findings in a slim, 114-page book, “New-Englands Rarities Discovered: in birds, beasts, fishes, serpents, and plants of that country,” published in 1672, complete with old-English typeface, woodcut illustrations of plants, and the charmingly random capitalization of the time.

“It’s the earliest description of New England’s plants and animals,” said Don Lindgren, owner of Rabelais: Fine Books on Food and Drink in Biddeford. “It’s a very rare book.”

Lindgren owns an edition published in the 1920s – not for sale – and his store has a 1972 facsimile published by the Massachusetts Historical Society selling for $35. An Oregon bookseller is offering a damaged first edition online for nearly $10,000. “I’ve seen non-defective copies selling for $18,000,” Lindgren said.

A list of marine life and sea birds compiled by John Josselyn in “New-Englands Rarities Discovered,” a compilation of observations Josselyn made during his two-year long walk throughout New England. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

But for non-collectors, the 350-year-old book’s appeal lies in Josselyn’s wondrous descriptions of nature in New England, practical advice gleaned from early settlers and Native Americans on best uses for animal meat and harvested plants, and the many natural remedies he peppered into the text. “New-England Rarities is a hymn of praise for American wonders, spiced by Josselyn’s delight in upsetting the applecart of the Old World with the unexpected New,” Maine historian Herbert Adams wrote in a 1984 issue of Habitat, the journal of the Maine Audubon Society.

Old-time remedies

Some of Josselyn’s suggested animal-based poultices and home remedies may seem fanciful or ill-advised today. Regarding cod, for instance, a fish he calls “a commodity” in early New England, Josselyn tells readers that “In the Head of this Fish is found a Stone, or rather a Bone, which being pulveriz’d and drank in any convenient liquor, will stop Womens overflowing Courses notably.”

As for osprey, Josselyn reports that “Their Beaks excell for the Tooth-ach, picking the Gums therewith till they bleed.”

Josselyn cautioned readers to beware the black bear “in rutting time,” when “they walk the Country twenty, thirty, forty in a company, making a hideous noise.” He reported that when bears invaded the “Mayne” town of Gorgiana, which is now York, settlers once killed “fourscore” of them. Beyond eating the meat, they used bear skins “for beds and coverlets,” and, like the Native Americans, applied the bear fat medicinally.

“Their Grease is very good for Aches and Cold Swellings, the Indians anoint themselves therewith from top to toe, which hardens them against the cold weather,” Josselyn wrote.

The book devotes 10 pages to listing more than 180 kinds of fish and shellfish he’d identified in New England waters. Lobster gets no special attention in Josselyn’s taxonomy, but he does introduce readers briefly to the “Clam, or Clamp, a kind of Shell Fish, a white Muscle.”

Illustrations from an original copy of John Josselyn’s “New-Englands Rarities Discovered.” Photo courtesy of Philip J. Pirages Fine Books & Manuscripts

Multi-purpose plants

But Josselyn seemed most impressed by plant life in the New World, which, he wrote, “for variety, number, beauty and virtues may stand in competition with the plants of any Country in Europe.”

“Some modern experts dismiss Josselyn as merely an eager herbalist, but the lone zealot – armed only with his ancient botanies and boundless delight – sought out dozens of new species unknown to science since Linneaus,” Adams wrote. “Likely no man living knew more about New England plants nor loved them more.”

Of Maine’s spruce trees, Josselyn stated, “It is generally conceived by those that have skill in Building of Ships, that here is absolutely the best Trees in the World, many of them being three Fathom about, and of great length.”

The book includes plenty of culinary tips, too. Josselyn cautions against eating New England hare in the winter, while their coats are white and they’ve been feeding on spruce bark, because it makes the meat taste bitter.

Regarding cranberries, which he also called bear berries because they ate so many, Josselyn said, “The Indians and English use them much, boyling them with Sugar for Sauce to eat with their Meat; and it is a delicate Sauce, especially for roasted Mutton: Some make Tarts with them as with Goose Berries.”

Lindgren said he believes the book refers to Maine’s native blueberries as “bill berries,” a similar fruit with which Josselyn was familiar. “They usually eat of them put into a Bason, with Milk, and sweetened a little more with Sugar and Spice,” Josselyn stated of the “sky-colored” berries, adding, “They are very good to allay the burning heat of Feavers, and hot Agues, either in Syrup or Conserve.”

“Plants did a lot of work for people then,” said Christine Buckley, the Florida-based author of “Plant Magic.” “Fiber, food, medicine, it was everything.”

Packed with herbal wisdom

Josselyn’s book features many home-remedy uses for New England’s elder, alder, wood sorrel, St. John’s wort and catnip. “These are all plants that people practicing herbalism still use today,” Buckley said.

Because Josselyn includes so much herbalist information, “some people think of this as a medical book,” Lindgren said.

Buckley explained that in the 17th century, “herbal medicine was being democratized, and recipes were being shared.” She noted that the landmark tome, “Culpeper’s Complete Herbal,” describing home remedy uses for plants in England, had been published almost 20 years earlier than Josselyn’s book.

“The Native Americans had their healing systems, and everyone who came (to the New World) did as well. They were all prepared to do healing work in their homes. The confluence of healing systems resulted in a rich pharmacopeia,” Buckley said.

“In those days, you were raised with this (plant medicine) knowledge. And if you didn’t have it, you probably wouldn’t live too long,” said J. J. Pursell, a naturopathic physician in Oregon, who recently authored an update to Culpeper’s book. “Every wound turned into a festering, pus-filled disease. Things were just not very clean.”

Colonial roadmap

While Josselyn’s book has obvious merits, Lindgren cautioned that when considered in full historical context, an early guidebook like this has a darker side as well. “It’s a really interesting personal project, but there’s an element of exploitation, conscious or not. It’s a roadmap for colonial exploitation,” he said, adding that he doesn’t think that was the author’s intent.

In another affront to modern sensibilities, Josselyn ends his travelogue with cringey descriptions of Native American women, whom he finds attractive and “plump as partridges.”

“Many of them have very good Features; seldome without a Come to me, or Cos Amoris, in their Countenance,” Josselyn wrote.

Still, the author at least partly offset these gaffes by helping a Native American man “whose Thumb was swell’d, and very much inflamed, and full of pain, increasing and creeping along to the wrist, with little black spots under the Thumb against the Nail.” Josselyn wrote that he whipped up a navelwort poultice, claiming, “I Cured it with this Umbellicus veneris Root and all, the Yolk of an Egg, and Wheat flower.”

Sure beats an osprey beak to the gums.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story