SKOWHEGAN — All that Twitters is not gold.

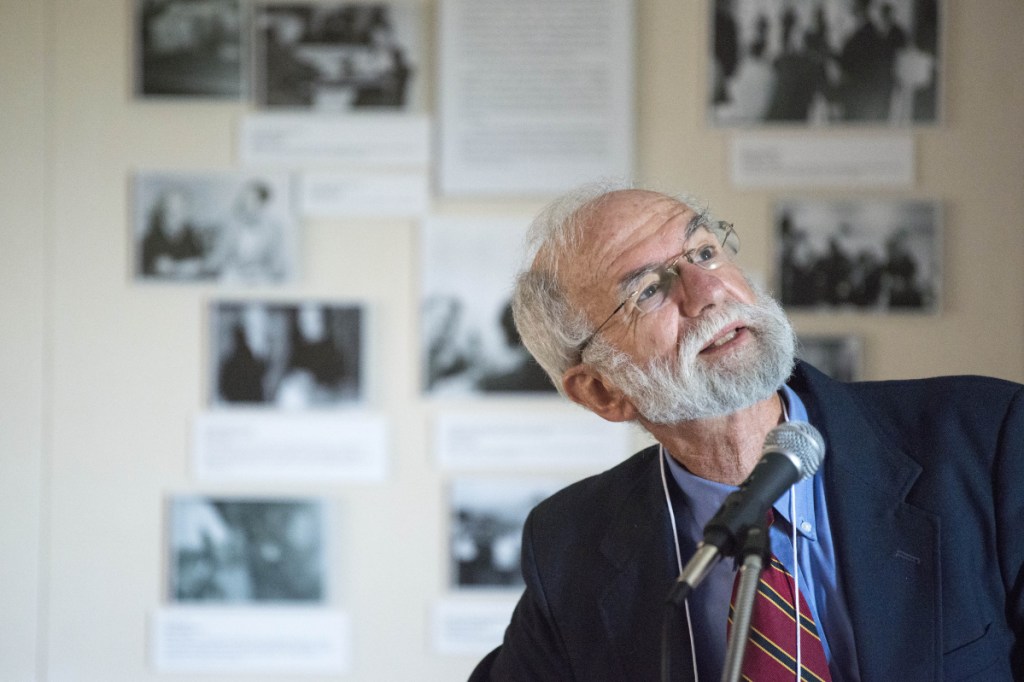

That quote from former journalist and senior federal official Chet Lunner was part of the tone Thursday during the 29th annual Maine Town Meeting at the Margaret Chase Smith Library. The theme of the two-part program was “fake news” and the evolving role of media in American society.

In introducing Lunner and Robert Brent Toplin, an emeritus professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and adjunct professor at the University of Virgina, Charles Cragin, president of the Margaret Chase Smith Foundation, noted that Tuesday was the 23rd anniversary of the death of the U.S. senator from Skowhegan and one day short of the 38th anniversary of Smith’s now famous “Declaration of Conscience” speech to Congress on June 1, 1950.

In his address, titled “Fake News from the Jefferson Administration to 2016,” Toplin quoted 17th and 18th century satirist Jonathan Swift, saying “Falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after it,” noting that fake news travels faster than the truth.

Now, with the internet and social media — the age of post-truth, he said, — information can be stretched to the point of being false, but it’s nothing new.

He said fake news dates as far back as the 1800 presidential election when Thomas Jefferson squared off against the incumbent U.S. president, John Adams. Jefferson won, but it was a “nasty, bitter campaign,” Toplin said, one filled with lies, partisan press and disinformation

“How far we’ve come since then,” he said to a round of laughter from the audience.

Adams was called a fool by the Jefferson camp and a man who wanted to become the American king.

“Thomas Jefferson — if you elect him, what would we have in America? ‘Murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest would be openly taught and practiced.'”

It was “the roots of fake news,” Toplin said.

So why does false news appeal to people, he asked rhetorically? Why do we fall for this stuff?

He said language and words are used as a kind of shorthand that stirs the emotions, but do not register as the truth, causing “cognitive dissonance,” which happens when our beliefs do not match up with our behaviors.

He said humans are tribal and side with others to make teams and political parties of like-minded people. The truth just gets in the way sometimes.

“People fall for this stuff because it simplifies the complex — a villain can be pointed to,” Toplin said. “A lot of this fake news touches on our fears.”

He said Americans will “find ways” to seek real news from responsible journalists “as we have in the past. We’ve been through this before.”

For Lunner, who was editor at the Kennebec Journal in the early 1980s, the idea of a fact checker on news items — an editor like the old days in newspapers — is one solution to kicking fake news off the internet. He said European countries have adopted GDPR — General Data Protection Regulation — to police social media and separate truth from misinformation within the European Union.

“I hate the term fake news,” Lunner said. “Technically, there’s no such thing, and the term itself is a great example of how sloppy our communication skills have become in our society. There is news — then there is propaganda, rumor, satire, lies, slander, gossip, talk radio, innuendo, hoaxes, unconfirmed reports, opinion, hearsay, commentary, rhetoric, comedy, hyperbole, before midnight infomercials, supermarket tabloid headlines, political speech and misinformation. It’s not news. Oh, and tweets.”

Lunner said as a former journalist he resents how easily all of those words have become interchangeable. He said he was taught accountability as a young reporter and the importance of what he called “gatekeepers,” real newsmen and women. He said fake stories are “corrosive and eat away at our democracy,” but, sadly, phony stories get more “clicks” than real news on social media.

Fake news posts on social media reached an estimated 146 million Americans during the 2016 presidential race, he said.

He said real people should replace the “algorithms” and robots that produce some of the news on the internet, but there still is some good news on the horizon.

Last year, Lunner said, the New York Times had its best quarter of subscriber growth in history, with 328,000 paid digital subscribers more than the previous quarter for a new total of 3.2 million print and on-line subscribers.

“That’s a heartening reversal of everybody getting all their news on social media,” he said. “We survived a civil war … we can get through this. I think the answer to our current fake news problem is a return to good old fashion, corny American values. We all need to get back to the basics: Practice mutual respect. Reach out to others who care. Slow down and think before you tweet.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story