HALLOWELL — In the middle of 1975, Hallowell’s mayor, Bob Stubbs, wrote about the Maine Department of Transportation’s plan to widen Water Street and called it a “perfect scheme to murder the city.”

The plan would’ve resulted in the department tearing down all the buildings on the river side of Water Street in order to construct a four-lane highway connecting Augusta and Gardiner.

State officials had wanted to reconstruct Water Street since the late 1950s. The upcoming project in Hallowell, while different than what the department presented more than 50 years ago, has been decades in the making.

The department, in 1958, recommended a four-lane highway be built through the city’s business district. The state purchased several dilapidated buildings in Hallowell and tore them down because they were thinking about expanding the road. The Augusta Gardiner Area Transportation Study, commissioned in 1975, included the recommendation, and construction of the new highway was scheduled to begin sometime after 1987.

A plan to improve the U.S. Route 201 corridor was estimated to cost between $9 million and $11.6 million, according to an official department document from 1975. The study said the “most immediate need for improvement existed in Hallowell between Milliken’s Crossing and Wilder Point Road.” The plan would’ve turned a 1.1-mile stretch of Water Street into a four-lane highway and would have required off-street parking to replace and add to what was available on Water Street at the time.

A state study in the 1970s said there hadn’t been any significant growth in traffic volumes on U.S. Route 201 between Augusta and Gardiner, accident rates on the stretch of road were less than the statewide average for similar-type highways and there was no anticipated traffic growth projected for the coming years. The summary said any improvements warranted in the corridor should be considered part of the Highway Commission’s normal construction programming activities.

“It came to a head in 1975 because of urban renewal,” said Sam Webber, a Hallowell historian, during an interview in his home. “It would have destroyed us.”

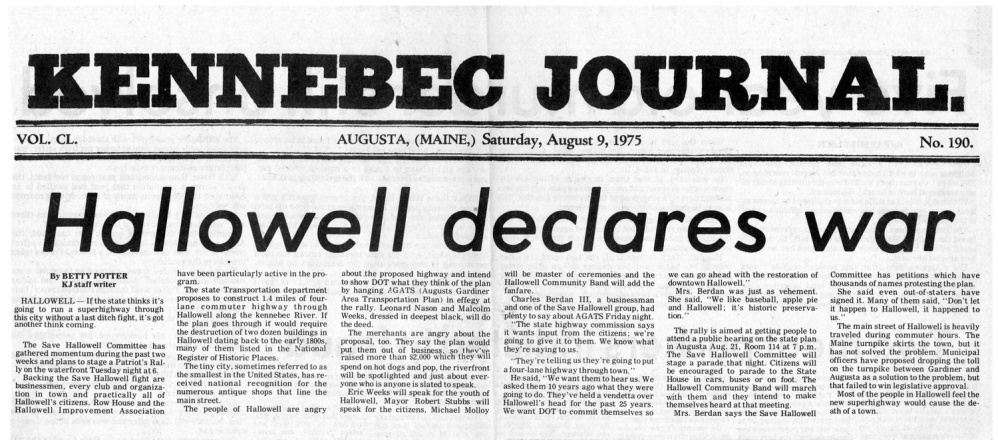

A group of concerned citizens including Linda Bean, the granddaughter of L.L. Bean’s founder, started a campaign to save the city’s downtown historic district. The mayor at the time, Robert Stubbs, distributed a press release in early August 1975 that called the state’s plan “the murder of a city.” He said the transportation department had devised a “perfect scheme to murder the city of Hallowell.”

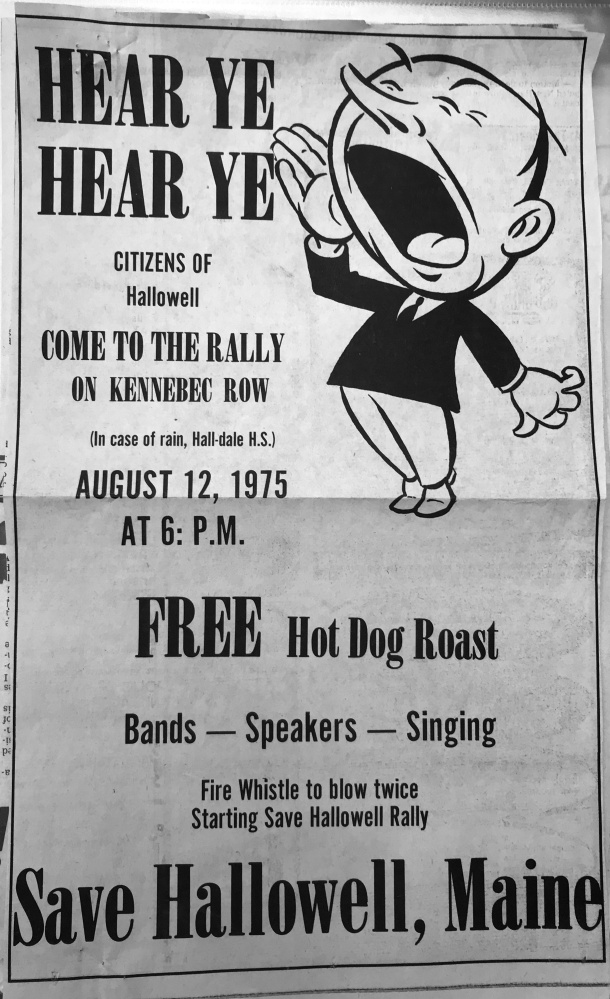

August 1975 coverage of Hallowell protest.

Webber said one of the mayors before Stubbs thought the federal money would be great for Hallowell and the city would get all the work done at no cost. Stubbs and others started the campaign to save the city that culminated in a march on the State House at the end of August 1975.

“(The plan) stirred up the hearts of the local Hallowell folks,” Bean said. “Thankfully, it didn’t happen.”

The transportation department is making final preparations to reconstruct a 2,000-foot stretch of Water Street in downtown Hallowell beginning in April. The project, which is expected to cost more than $4 million, will run until at least October and right through the downtown business districts busiest summer months. There is a crown in the road that will be repaired, there will be new sidewalks and reconfigured parking spaces, and several other below-the-surface improvements are expected.

The state study in 1975 said there had been no significant growth in traffic on U.S. Route 201 between Augusta and Gardiner — which included Water Street in Hallowell. The study said traffic accidents are less than the statewide average and the study didn’t anticipate any substantial increases for the corridor in the future. The department, however, went forth with the plan to turn Water Street into a highway.

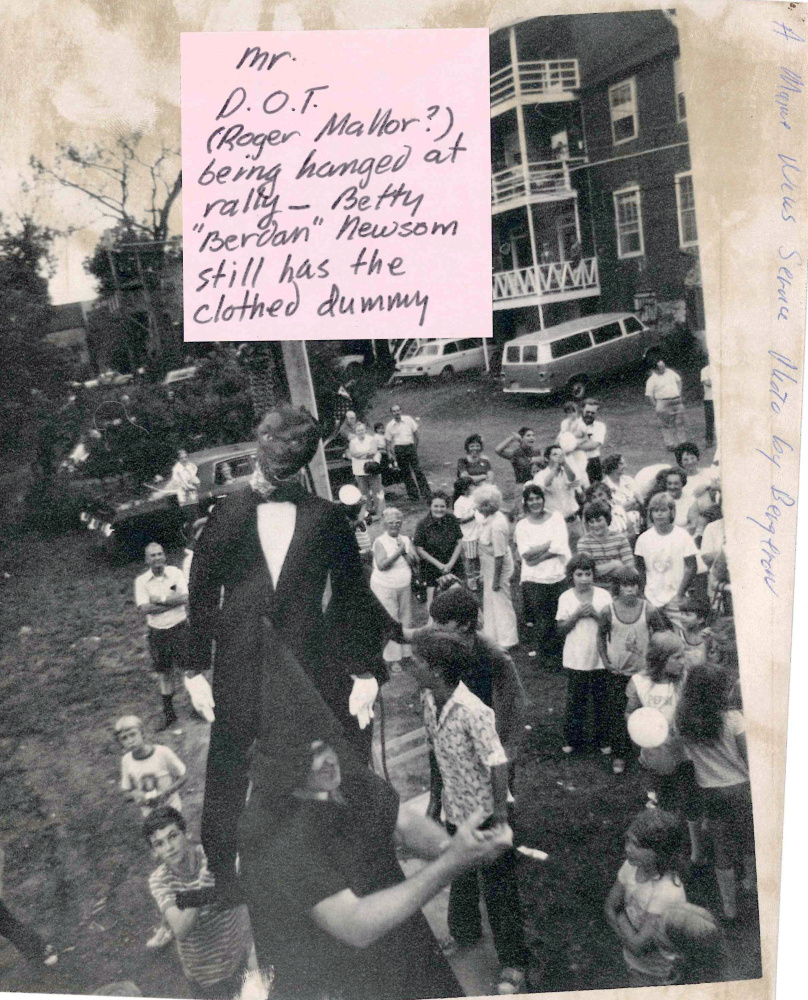

“There was going to be a hearing with DOT leader Roger Mallar,” Webber said. “Mr. DOT, as we called him, canceled the meeting because it was a circus-like atmosphere.”

Mallar died in October last year, but his son Mike, who lives in Augusta and owns Mallar Decoys, said his father wasn’t bothered by the criticism he received from people in Hallowell and continued to patronize Hallowell businesses the rest of his life.

“He thought it comical that a bunch of ‘junk shops,’ as he put it, thought that widening the road and taking out the hump would have some sort of negative impact,” Mike Maller said. “The road still hasn’t been repaired, and it sure is a lot of fun to get your door stuck on the curb and damaged because of a short-sighted minority.”

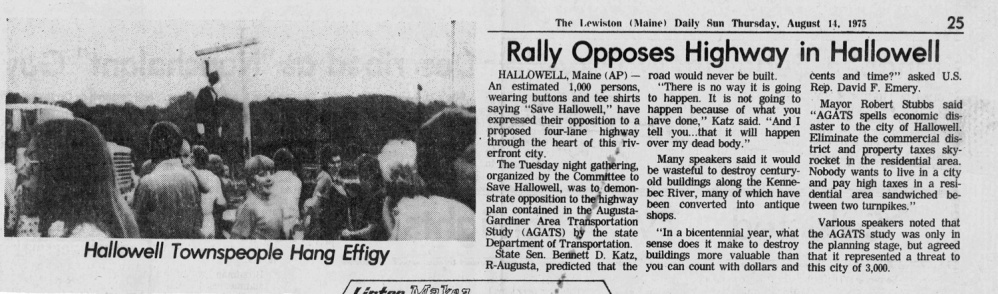

The first rally opposing the plan was held Aug. 12 on Front Street in Hallowell. The rally was a unifying moment for the people of Hallowell, who were almost unanimous in disapproving of the department’s plan to turn a stretch of Water Street into a multi-lane highway.

“We had to stay vigilant,” Webber said.

The transportation study called for the demolishing some, if not all, of the historic buildings on the east side of the Water Street business district, which were in the 207-acre national historic district designated in 1970 after Bean and others from a preservation group called for a federal review.

Bean was part of an eight-person group that walked around Hallowell informally studying the architecture of Hallowell. They walked around once a week, taking pictures of each house and learning facts about the house.

“We learned a lot, and we decided we had to find out how we could stop (the DOT plan),” Bean said. “It was a nice study group.”

The project would have eliminated several businesses and residences on Water Street, and Bean said it would’ve been a speedway through Hallowell.

Sun Journal Aug. 15, 1975, coverage of Hallowell protest.

Following the rally in early August, Mallar planned to hold a public hearing at the State House. Residents of Hallowell planned to march to the State House to protest the DOT plan, but instead, Mallar canceled the hearing — citing a “carnival-like” atmosphere — two days before it was scheduled.

Mallar acknowledged that the public’s concerns and message had been heard, and he offered to meet with Hallowell citizens to discuss alternatives to the DOT plan. Rather than agree to the meeting, about 400 “Save Hallowell” supporters marched to an empty State House the night of the canceled meeting, Webber said.

They gathered around a scaffold-adorned flatbed trailer and listened to speeches supporting the preservation of downtown Hallowell’s historic business district. The rally ended with Mallar hanging in effigy.

Mike Maller said his dad didn’t regret anything because his job as the commissioner of the department was to propose and make changes that people sometimes found difficult.

“He simply proposed something that would have served well the patrons of the shop owners in Hallowell over time, rather than a few nuts in Hallowell who had nothing better to do than burn my father in effigy,” he said. “He used to say that everyone wanted to be in charged but few were OK with the responsibility that go with it.

“He also said do not ever get into a fight with a skunk,” Maller said.

State historian Earle Shettleworth said he remembers people being thankful the project didn’t happen because of what an important part of the commercial and civic life of the community downtown Hallowell has been for more than a century. He compared it favorably to the Old Port in Portland because of the presence of vital activities happening during the day and the evening.

“There is a very distinctive historic fabric along Water Street that really defines the character of the area,” Shuttleworth said. “It’s a very powerful force.”

Shuttleworth said Water Street in Hallowell was developed in the early 1800s as a traditional commercial street in a Maine downtown. Hallowell suffered an economic downtown after World War II, Shuttleworth said, and the downtown was economically stressed; by the 1950s, there were a lot of empty shops on Water Street.

“Hallowell was very lucky that those shops attracted antique dealers who like big buildings and low rents,” he said. “It was the antique shops that really saved Water Street.”

The antique shops saved the economy of Water Street in the middle of the 20th century, and a group of concerned citizens helped save the street itself. Shuttleworth said Hallowell is preserved and desirable because of its citizens and their desire to protect their city. He said they’ve always rallied to protect their community.

“This kind of spirit that emerged in Hallowell at the time over (the DOT plan) is characteristic of Hallowell, where people take a deep interest and pride in the character and fabric of the community,” Shuttleworth said. “The results speak for themselves.”

Jason Pafundi — 621-5663

Twitter: @jasonpafundiKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story