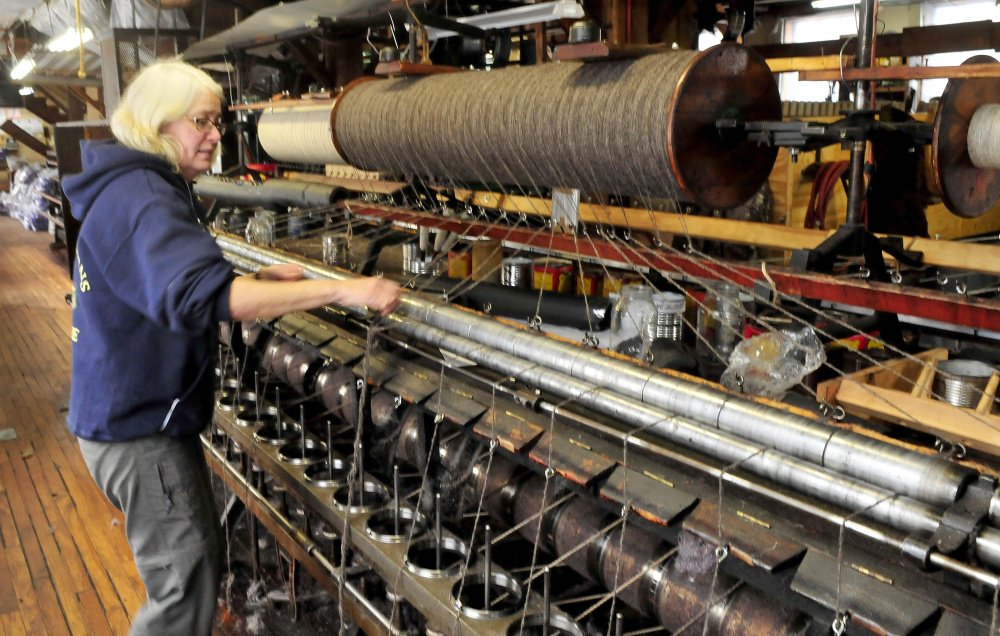

HARMONY — A 150-foot-long spinning mule races back and forth on steel wheels and thin rails like a small railroad train at Bartlettyarns woolen mill in Harmony.

Built in 1948, the mule is spinning 240 bobbins of wool into yarn and it’s the last of its kind in the United States, said Lindsey Rice, who with his wife, Susan, owns and operates the three-story woolen mill on the banks of Higgins Stream.

The textile mill has been in operation on the same spot since 1821, powered first by a water wheel that was replaced by a water turbine and then finally converted to electricity.

“In 1920, the original building burned and was replaced with the building that you see today in 1921,” Rice said. “For its day, it was very modern — a lot of windows, metal clad siding, metal roof making it fire resistant.”

One of the machines inside the mill — a round rover — dates back to the 1880s, and most of the iron and wood equipment has been in use since the early 1900s. The Rice family bought the place in 2007 from Russell Pierce, who had owned it for 24 years.

The wooden floors are shiny and bright from decades of lanolin from the wool and machine oil from the equipment, like a working museum. Stairs, beams, spools, even a bobbin holder all are made of wood.

But some upgrading is in the works.

Known for its wool yarn, wool roving, knitwear, weaving, rug yarns, supplies and gifts, Bartlettyarns this month was named one of eight finalists to be a recipient of a Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry grants totaling $250,000.

The Rices would use the grant money to upgrade their operation with a commercial wool baler if they received the grant.

“Bartlettyarns is pleased to have been selected by the state to receive this grant,” Rice said. “We currently pack our wool manually, which is the traditional method, but the new equipment we are hoping to acquire will greatly increase the density of our packed wool.”

The company ships the raw wool from farmers to be washed. A typical tractor-trailer holds about 20,000 pounds of wool because of how the wool is packed, he said. With the new equipment they will be able to increase that weight to more than 45,000 pounds per load. The bales will be more uniform in size and shape, which will make handling easier, he said.

The baler will come from Australia because balers of that type are not made in the U.S.

Seven people are employed inside the old factory and one more at the reception desk in the main office and retail shop across the street from the mill.

Rice said raw wool is bought from sheep farmers all over the Northeast, including North Star Sheep Farm, which has 3,500 sheep in Windham.

The wool is delivered to the mill receiving shed on Water Street in Harmony and shipped off to South Carolina to be commercially washed, then dyed in Philadelphia and returned to Maine to be made into yarn.

“They do the shearing and sell us the raw wool, and we’re taking that raw wool and making it into the yarn and it becomes a Christmas stocking or a wool sweater or goes to a shop,” he said.

The process of making the yarn begins in the basement of the mill, an area which was used as a set for the Stephen King movie “Graveyard Shift,” filmed on location in 1990.

Old machinery, one piece called a duster installed in 1935, which tumbles the wool to loosen it up, and another called a picker, which teases and opens up the fiber, sit in the basement and are the first stops on the way to making yarn. The loosened wool is then blown into a holding room, also in the basement, where 30-year-old graffiti decorates the wall.

A recent visit found wool already dyed bright red cranberry for Christmas stockings that Rice said a company in Wisconsin knitted.

The upper two floors hold a gaggle of perfectly working antique machinery, including a “carding” machine made in Boston in 1919 and a 1928 twister. Some of the equipment still uses leather belts to run the machines with steel cog wheels and ancient metal weights.

But the main attraction at Bartlettyarns is the spinning mule running back and forth on the railroad tracks, which twists the thin yarn fiber into stronger thicker yarn.

“The principle of the mule is to duplicate the motion of a hand spinner,” according to the company’s website. “In hand spinning, the spinner’s hand moves to and from the tip of a spinning bobbin. Raw wool fibers are snagged onto the end of the bobbin and are drawn and spun between the tip of the bobbin and the spinner’s fingertips.

“In mule spinning, a carriage contains a row of bobbins, moves back and forth, simultaneously drawing and spinning a six-foot length of carded roving attached to each bobbin.”

There still are four textile mills in Maine, including one in Etna, which has state of the art machinery, Rice said.

“We specialize in making knitting yarn,” Rice said. “We don’t deal with any big box stores. Everything that we do goes to local yarn shops where they’re working with that local hand knitter. We’re still working directly with the consumer and the farmer.”

One of the local shops that uses Bartlettyarns products is Happy Knits, a shop inside the Somerset Grist Mill complex at the former county jail in downtown Skowhegan.

Rice said it can take six months to a year to learn all the jobs at Bartlettyarns.

Rice said the company’s inventory includes 65 different colors of finished yarn in five different weights and thicknesses. He said some of the yarn is knitted into sweaters at a mill in Fall River, Massachusetts. The sweaters and knitted hats are sold in the Bartlettyarns shop and other locations in Maine as well as a store in Japan. Other items at the Harmony shop are knitted locally as piece work with materials provided by the company, Rice said.

The Harmony woolen mill is one of a dying breed of Made In America textile outlets, Rice said.

“The spinning mule on the third floor, that’s the last commercial operating one in the United States,” he said. “There are other mills nationwide. Maybe two dozen of us left.

“We’re not a museum — we’re a production mill.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story