Halloween arrives this weekend, so let’s talk about something truly scary.

It haunts our kitchens, slithers into our conversations and lurks in the foods we eat. It has wormed its way deep inside our most trusted institutions, yet most of us can live our whole lives without noticing its spooky inconsistencies.

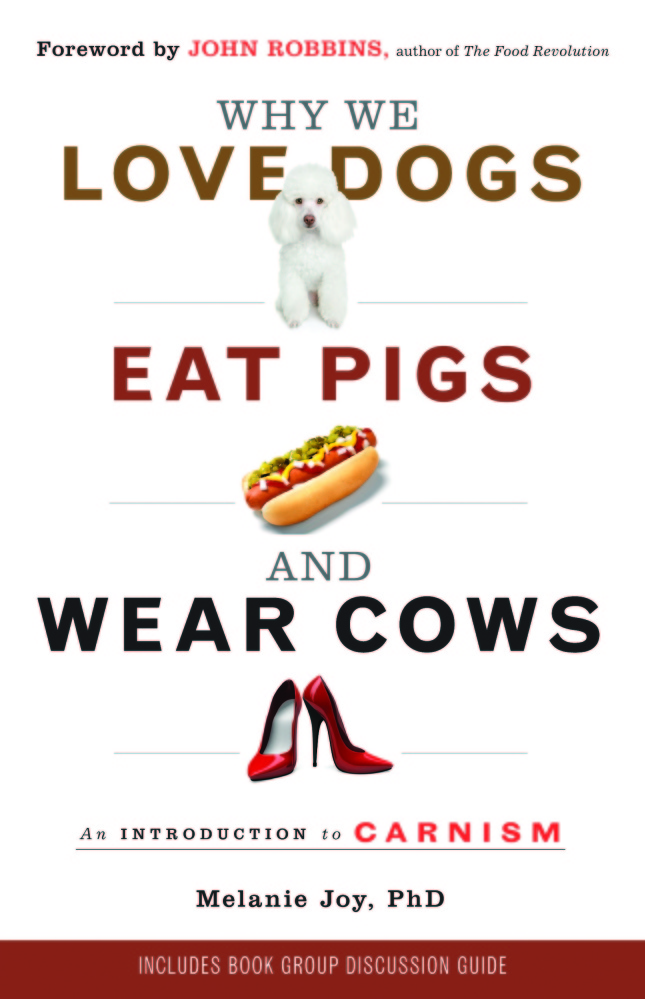

I’m talking about the ideology known as carnism. The term was coined in 2001 by Melanie Joy, a Harvard-educated psychologist who wrote the 2011 book “Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows” and founded Beyond Carnism.

Carnism, according to Joy, rests on the belief that eating meat is normal, natural and necessary, the three Ns, as Joy calls them.

Joy says carnism is similar to racism and sexism, in that all use psychological mechanisms to numb our instincts for equality, justice and empathy.

Carnism is related to the better known ideology of speciesism, which teaches us that human and nonhuman animals have different moral worths. The term’s roots stretch back to the early 1970s and the philosophers Richard Ryder and Peter Singer.

While it is unsettling to discover the ethical problem inherent in the belief that it’s OK to eat baby cows but not OK to eat baby horses, Joy says being a participating member of a culture dominated by carnism doesn’t make us all monsters.

“It’s important to recognize good people can participate in harmful behaviors, but that doesn’t make them bad people,” Joy told me via Skype from her office in Berlin, Germany, where she is based during a leave from her teaching position at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “Most people would not willingly harm animals. Carnism needs to use these defensive mechanisms that operate on a social and psychological level to numb our feelings. They are largely unconscious.”

Joy said the ideology of carnism holds fast even when the animals being eaten change.

“In meat-eating cultures all around the world, people learn to classify select animals as edible,” Joy said. “The animals classified as food change from culture to culture. I’ve spoken about carnism on five continents, and I’ve never seen an exception.”

Joy spoke at the Portland Public Library in 2011.

In “Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows,” Joy writes: “a Hindu might have the same response to beef as an American Christian would to dog meat.”

MEAT INTERRUPTED

Joy begun delving into these ideas after she experienced food poisoning from eating a contaminated hamburger. When she recovered, she said meat provoked a very negative, visceral reaction and she could no longer eat it. Joy said having this conditioned behavior – eating meat – interrupted “made me more open” to discovering the invisible ideology in which she had actively participated.

“I was shocked when I learned about what happens to the animals who become our food,” Joy said. “It is a horror beyond description. But everyone told me: ‘Don’t tell me that. You’ll ruin my dinner.’ That made me realize there was something going on psychologically. But I didn’t know what it was. I went looking for it.”

In pursuit of her doctorate, Joy interviewed vegetarians, vegans, meat eaters, butchers and farmers about their attitudes toward animals and meat.

“On one hand, people cared about animals, but on the other hand, they ate or butchered animals,” Joy said. “Even the vegetarians and vegans had exactly the same attitudes. These widespread contradictions don’t exist in a vacuum. There has to be a belief system. When people make exceptions to what they normally consider unethical, and it is happening on a massive scale, the only explanation for it is ideology.”

But before Joy documented the carnistic defense mechanisms that say meat-eating is normal, natural and necessary, she said she first had to break through carnism’s primary defense mechanism: Denial.

We build high walls around confined animal feeding operations and their related slaughterhouses for a reason. And whenever you hear someone grilling the vegetarian at the dinner table or bullying vegans online, you’re witnessing what Joy calls secondary carnistic defense mechanisms. People wall themselves off from the uncomfortable truth by trying to silence those who question meat-based diets.

BACON WITH CHEMO

Joy says health and nutrition advice from conventional medicine specialists is among the places carnism is most visible.

“This is a powerful bias that informs nutrition and medical institutions,” she said. “When you’re studying nutrition, you’re studying carnistic nutrition,” complete with the mythology that eating meat is normal, natural and necessary.

Having once worked in a hospital filled with brilliant minds, I’d always wondered why medical centers feed hamburgers to heart attack patients and bacon to children recovering from chemo. Now I understand.

Joy said a more recent manifestation of carnism is the concept of “humane meat.” The word humane is defined as having or displaying compassion for people, animals and the less fortunate, and when combined with the word “meat” it forms the mixed-up concept of compassionate slaughter.

“Most of us would consider it cruel to kill a 6-month-old happy, healthy golden retriever just because her thighs taste good,” Joy said. “We would never say, ‘The dog had a good life, so it’s OK to kill and eat her.’ ”

Yet good, well-meaning people buy “humanely raised” baby sheep every day. They call it lamb and serve it to loved ones.

“We internalize this distorted belief that food animals are things rather than living beings,” Joy explained, “and that animals belong in categories – some are eaten, some are loved. These defense mechanisms create psychological distance between us and the meat on our plates.”

But Joy hasn’t lost all hope. Humans, she said, have a track record of breaking free from oppression.

“Once we can see carnism,” Joy said, “it loses much of its power over us. Because carnistic defenses are illusions. They’re myths. When people of conscience become aware of injustice, they speak out and they stand up for what’s right and they often choose to be conscientious objectors. History shows us again and again: People demand change when they become aware of oppression.”

Avery Yale Kamila is a freelance food writer who lives in Portland. She can be reached at

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter: AveryYaleKamila

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story