There is a growing stack of brain scans that shows what concussions and collisions can do to the cognitive function of professional football players.

But the harmful effects of repeated brain trauma are hardly reserved for the NFL, or even football in general.

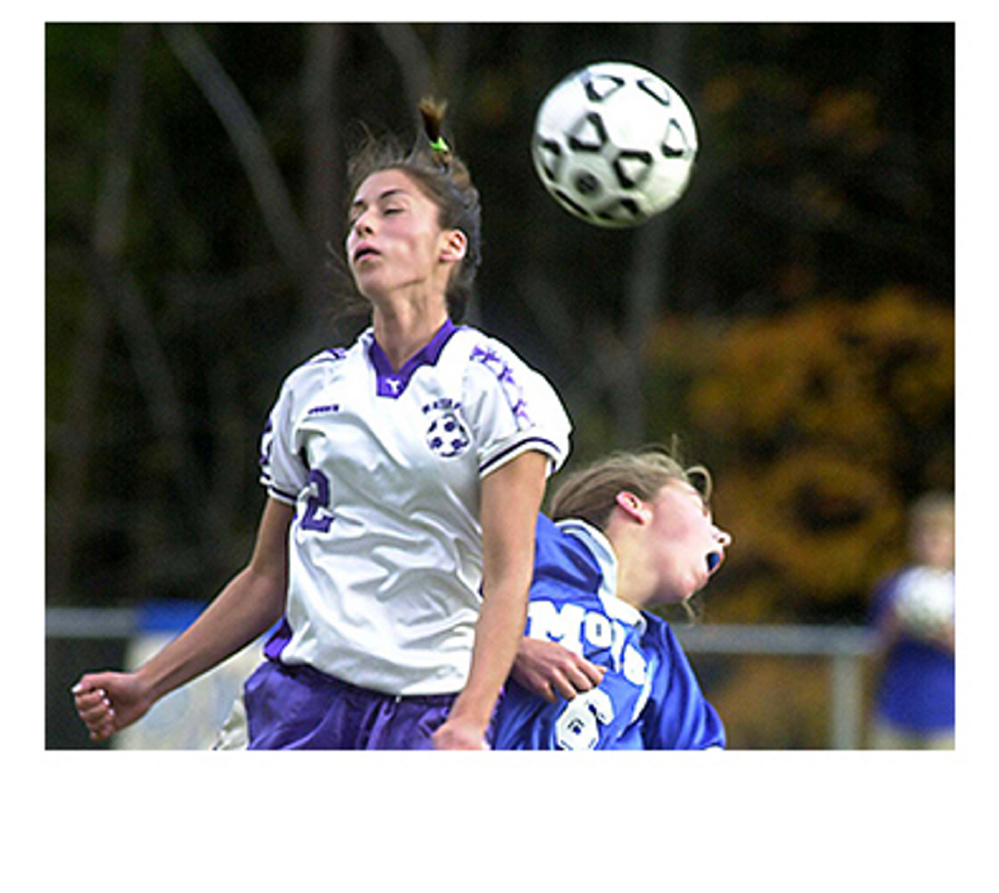

Concussions are an overlooked problem for high school athletes, and while football leads the way, soccer, lacrosse and hockey also pose a danger, and girls are particularly at risk.

The danger is not risky enough to keep kids from playing sports, but it is imperative everyone involved knows how to spot the symptoms of a concussion, and that player safety and well-being are the foremost concerns in youth and high school sports.

The numbers on concussions vary. One study puts the prevalence for high school football players at 11.2 per 10,000 “athletic exposures,” or the number of practice and games in which an athlete participates, and at 6.7 per 10,000 exposures for girls soccer. Another puts the rates at 6.4 and 4.5, respectively.

But because parents and coaches can miss the symptoms, and student-athletes often don’t want to pull themselves out of games or practice, concussions are underreported.

With so many students taking part in athletics — more than 375,000 nationwide in high school girls soccer alone — that leaves a lot of teenagers open to long-term damage.

That’s because concussions are traumatic brain injuries that require a slow recovery, with lots of rest and little physical or mental stress.

However, since so many go undiagnosed or unreported, and because there is often pressure to return to action, student-athletes can cut that recovery short, leaving them more susceptible to another concussion, and further damage on their still-growing brain.

Just how bad that damage can be is still largely unknown. There has not been much research on the long-term consequences of concussions on youth athletes, nor has there been sufficient nationwide tracking of concussions and the circumstances in which they occur.

Both would help improve diagnosis and recovery plans, and determine if actions like mandatory protective equipment or rule changes would help deter concussions.

But no further study is needed to know that student-athletes suspected of having a concussion should not play until they are cleared by a doctor, and those found to have suffered a concussion should not return to practice and games until all symptoms have cleared and they have a physician’s OK.

A Maine law passed in 2012 codified that policy for all high schools, an important step for raising awareness and changing a sports culture that sometimes makes returning from injury an issue of toughness, rather than health, particularly with an injury like a concussion, which can have no outward signs.

But tools used to immediately assess whether a player has suffered a concussion are imperfect, and athletic trainers who know what to look for can’t be at every game and practice.

That makes it necessary that coaches and athletic administrators foster an atmosphere in which players feel comfortable reporting a concussion.

And it leaves it up to coaches, officials and parents to make sure players are watched closely after a collision on the field, and not only in football.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story