On the surface, it seems like simple math: Maine’s 491 municipalities and 16 counties are just too many, and reducing both would make local government more efficient and less costly.

But an example to our north shows why it’s not that straightforward.

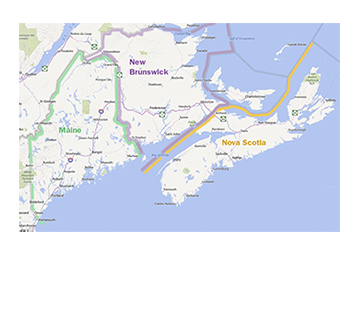

As reported in the Maine Sunday Telegram, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have been consolidating towns for decades, for the same reasons that make regionalization attractive here.

The results, however, have been mixed, and they offer some lessons on how Maine should proceed in order to change the delivery of government services for the better.

In both Nova Scotia — a province two-thirds the size of Maine where there are just 28 independent towns, plus the Halifax metro area — and New Brunswick, some small towns formed much larger units, either by joining together themselves, or by merging with nearby large cities.

What both provinces found, for the most part, is that when consolidation involved large numbers of residents, such as in the case of Halifax, which absorbed two of its neighboring cities, savings did not materialize, and in some cases services were diminished.

However, there was, it can be argued, a more fair distribution of costs, as the once-separate smaller towns were forced to picked up some of the burden for the regional services offered in the bigger cities.

That could have an application in Maine, particularly in the more rural areas where one large city, such as Waterville or Presque Isle, now pays for infrastructure and services enjoyed by many residents who live outside its borders.

There’s something to learn in the other, smaller mergers, too.

In New Brunswick, there were many small, rural towns that for years lost population, forcing them to partner up to survive.

Unlike the larger consolidations, these were mergers of necessity, entered into voluntarily and involving relatively small number of residents.

In those cases, it was possible to cut the number of employees and elected officials.

To one observer, that makes consolidation a question of finding the right number, where economies of scale can be reached, but residents still have a voice in how services are delivered.

“I can tell you that once you get over about 20,000 people, you lose control,” said David Corkum, a past president of the Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities, “but also that towns of less than — I hate to say it — 3,500 people probably shouldn’t exist.”

The experience in Canada, then, shows that consolidation is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

It will look different in the northern, western and central parts of the state than it does in the south and east. And it will look different in rural towns than it does in suburban and urban areas.

Those differences, in part, doomed the school consolidation effort in Maine, as did the top-down nature of that effort.

That’s where another lesson comes in. Towns must be able to join together based on their particular needs, and under their own particular terms, informed by the successes of other Maine municipalities that already are sharing and regionalizing services, and backed by state policies that encourage cooperation.

Down the line, as Maine’s demographics continue to shift, more dramatic changes may be needed.

But for now, we could do a lot worse than learning from Canada.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story