At first it sounds like an exercise in mechanics, perhaps yet another hagiography, a tome out of the writings of another Hollywood saint. Don’t we all, by this time, know enough about Marlon Brando, the “greatest actor of his generation”?

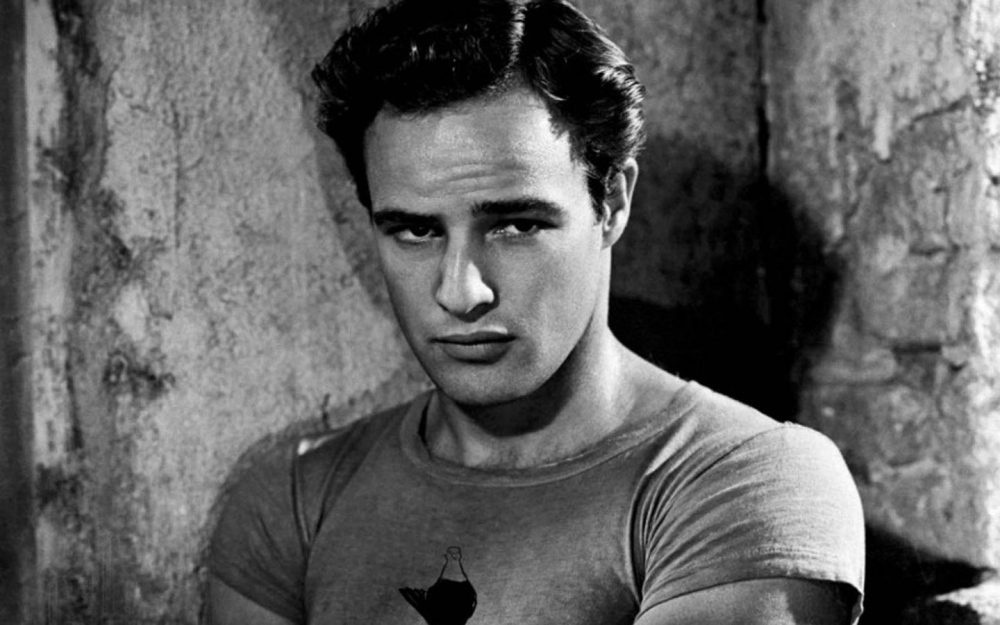

Most of us have seen all of his films, from “Streetcar Named Desire,” to “Apocalypse Now,” the stunning “On The Waterfront,” to his brilliant “The Godfather.” He was a star brightly shining, then falling to Earth and crashing, fueled by his physical weight and addictions.

But now comes something else, a documentary that is so much more. This week we receive a gift from British writer, director and editor Stevan Riley, a 102-minute journey through Brando’s life, full of great film clips, interviews, home movies and stories told by Brando in his own voice, drawn from thousands of self-hypnosis tapes.

The visual process itself, a unique 3-D image of Brando’s head, created by Brando himself, employing a software called Cyberware, makes it appear as though the actor is speaking from beyond the grave.

As Brando speaks, and we journey with him through various relationships, films, rehearsals and the court trials involving his wives and some of his 16 children, we find ourselves caught up in a final, beyond-the-grave movie, written by Brando himself. It’s haunting and exciting, mysterious and compelling, at once maddening and sad. It may be the finest, most original documentary ever made.

We see scenes from his films, the masterpieces and the trash, all narrated by Marlon, as though we stand beside him on the sidelines, watching history unfold. Imagine hearing Shakespeare explain Banquo’s ghost.

Even more ghostly are the scenes in Brando’s Mulholland home, overlooking the twinkling lights of Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley. Director Riley recreated the interiors from home movies and still shots. He fills the scene with foggy twilight and shadows as though it still existed, but the home was torn down years ago; another home with other rooms full of other voices stands there now.

One can imagine Marlon walking the halls, searching for clues.

Brando, with the magic of new technology, seems to rise from his sepulcher, teasing and flirting in old interviews, making fun of himself in Falstaffian bursts of laughter, and in heartbreaking newsreels, bursting into tears at his son Christian’s journey to prison, and his daughter Cheyenne’s funeral after her suicide.

He speaks of his alcoholic mother’s brilliance and nocturnal wanderings, his abusive drunk of a father, and all of his childhood that informed the rest of his life. All of this we’re witness to, as though we’re on a Disney ride through the sun and darkness, the emotional storms and Tahitian sunsets.

Writer Riley sits us behind the corpulent Brando on his patio and darkened living room, as he shows us his virile, sensual young self, dancing with Sinatra, fighting to the death on the waterfront, making love to Vivian Leigh and Tahitian princesses, bringing Emanuel Zapata and Christian Fletcher to life, to making us gasp at his transformation into Don Corleone.

We get the full Brando, whom one critic once described as “intellectual, prankish, evasive and brutally frank.” He was all of those things and brilliant and tender as well. His name was spoken and printed as either “Brando” or “Marlon” — it didn’t matter — and both instantly evoked the image of a larger-than-life demigod.

He was Brando, a man Shakespeare might have described as he did Othello, “one that loved not wisely but too well.”

J.P. Devine is a former stage and screen actor.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story