OAKLAND — The Friends of Messalonskee are doubling down on their battle with invasive milfoil, which is threatening to choke up parts of the 10-mile-long lake.

The lake association last year launched a pontoon boat retrofitted as a DASH, or diver-assisted suction harvester, to tackle the virulent weed, which has crept into coves along the Messalonskee Lake shore. A second DASH boat was unleashed this summer.

Although they probably never will get rid of the weeds entirely, the Friends think they have a handle on the problem and have mapped out the areas of greatest concern.

“It doesn’t feel like it’s out of control,” said Mike Willey, a Friends of Messalonskee board member. “There are certainly places where there is heavy milfoil, but we think we have a plan to deal with it.”

With the two teams working all summer, organizers hope that they can make serious headway against the milfoil infestation.

“We’ve made great progress, but to really attack it quickly, we just thought that having another set of divers and another boat would help,” said Anne Hammond, treasurer of the Friends of Messalonskee.

Even with new resources, it could take years to address the problem, especially on Belgrade Stream, where an intense infestation threatens to smother the waterway.

On Wednesday, nearly 30 divers, three DASH boats and more than a dozen kayaks were in the water near the Oakland public boat launch for an annual training put on by the Department of Environmental Protection. This is the first year that DEP has required the training for dive crews, using funding from the department, and included instruction on plant identification and harvesting.

Hammond observed the practice from the deck of a pontoon boat captained by Willey.

The dive teams will work in 16 Maine lakes and rivers this year, slowly turning back the tide of the invasive plants.

Variable-leaf milfoil is an aggressive aquatic weed that spreads quickly and is notoriously difficult to remove. The plant grows in shallow water and forms thick, impenetrable mats that can crowd out native plants and wildlife and ruin the shoreline for recreation.

Milfoil fragments can take root and quickly grow entirely new colonies. The plant has hitched rides on traveling motorboats, spreading to more than two dozen lakes, ponds and rivers in central and western Maine. The state now imposes tough fines for those found to be transporting milfoil and requires owners of motorized boats to buy an annual milfoil sticker to help fund eradication and prevention efforts. Courtesy boat inspectors are a normal presence at public boat ramps, where they check propellers, hulls and other parts of boats for unwanted hangers-on.

Prevention is key, because once milfoil takes root, removing it is a struggle.

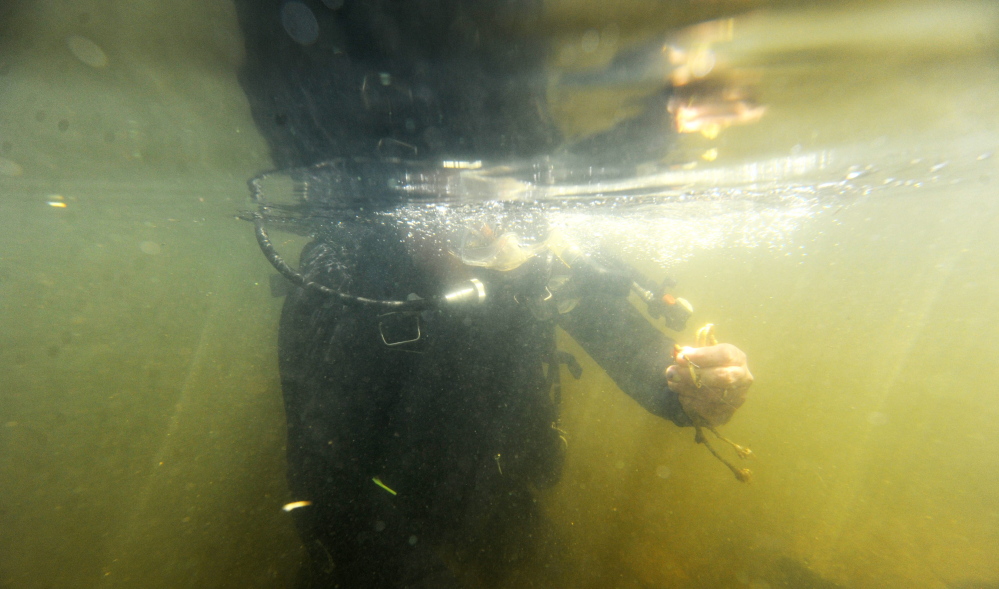

An effective but time-consuming method is employing teams of divers to hand-harvest milfoil one plant at a time. Teams also put down heavy plastic tarps, or benthic barriers, to deprive young milfoil plants of sunlight.

Milfoil was discovered in Messalonskee Lake in the late 1990s. It also has been identified in Great Pond, Great Meadow Stream and Belgrade Stream. In 2007, the Friends started the first eradication efforts.

In its 2009 milfoil management plan, the Friends identified major infestations in the wetlands on the south end of the lake around the outlet from Belgrade Stream, a cove near Juniper Lane on the southeast side, a cove on the northwest shore near the Willey Point causeway and in and around the Oakland boat launch.

The plan is to attack high traffic areas, such as the boat launch, that pose a risk of transmitting the weed to other parts of the lake or other water bodies, Willey said. After that, the group will take on areas where milfoil is just setting in before tackling locations with serious infestations.

The Friends first contracted with a DASH boat operation, but the thousands of dollars for that service meant that they could afford the private operators for only a few weeks.

Last year, with help from Hamlin Marine, of Waterville, the organization launched its own DASH boat, a pontoon barge retrofitted with a suction engine and vacuum tubing. Flying red and white diving flags, the boat floats above the extraction site, assisting the divers digging up the plants under the surface. The dead plants are sucked up with the tube and deposited in mesh onion bags on the boat.

In the first summer, dive teams pulled 50,000 pounds of milfoil from a cove opposite the Oakland boat launch, Hammond said. This year, there were 2,000 juvenile plants sprouting in the same area.

The fighters at Messalonskee Lake and elsewhere take comfort from the example set by the Lakes Environmental Association in its own struggle against a notorious infestation on the Songo River and Brandy Pond, the waterway connecting Sebago and Long lakes in western Maine.

That association put a DASH boat in the water in 2007 and began an aggressive anti-milfoil operation with teams of six to eight divers working 40 hours week. It started at the mouth of the river and gradually moved into the heavily-infested center.

Seven years later, the group declared a guarded victory, reporting that most of the water was clear. The association continues monitoring, but the waterway is largely back to its natural state.

“The message we try to convey to other groups is that if you make an efficient plan and you are able to do it steadily, it’s possible,” said Adam Perron, Lakes Environmental Association’s invasive plant coordinator. “We’re not the only success story.”

Milfoil also is being beaten back in other parts of the Belgrade Lakes watershed.

Salmon Lake, in Belgrade, was taken off the state’s list of infested lakes last year after a patch of superinvasive Eurasian milfoil was destroyed with an herbicide treatment in 2010. It is one of four lakes that have been de-listed by the state.

The Belgrade Regional Conservation Alliance acquired a DASH boat last year for an eradication program on Great Pond and used contractors to extend its harvesting season through September, said Charlie Baeder, that group’s executive director. Those tactics knocked milfoil in the lake down 80 percent, he estimated.

“We expect to have to continue to go back there and keep pulling plants,” Baeder said. “It’s an ongoing effort. We’re out there again this year.”

More lake and conservation associations are acquiring the equipment to start tackling milfoil invasions, said Roberta Hill, an aquatic ecologist who works for the Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program, a statewide lake conservation organization.

A few years ago, federal grant money was freed up to help local groups buy DASH boats and equipment, and Maine DEP has modified how it distributes revenue from the milfoil stickers to emphasize eradication efforts, Hill said. Groups can’t expect to clear milfoil with eradication exclusively; they need to pair it with a long-term plan emphasizing monitoring and prevention, she added.

Moreover, all the federal and state funding won’t help without the efforts of local groups that are on the front lines raising money, organizing and putting in the hours to fight back and control milfoil and other invasive species, Hill said.

“They’re the ones who are really stepping up to the plate,” she said.

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Twitter: PeteL_McGuire

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story