Michael Pelillo, the chef at Pen Bay Medical Center, has heard all of the stale jokes about bad hospital food. He spent most of his 45-year culinary career working in hospitals and rehab centers, and he has seen everything – the lime gelatin, the mystery meat, the mixed vegetables that look as if they were harvested during the Eisenhower presidency.

“I’ve seen things that would scare people,” he joked.

Now Pelillo is working at a hospital that has, at least for the past few years, dedicated itself to serving as much local food as possible. Instead of frozen fish sticks, patients and staff are served picked crab, haddock, redfish, monkfish and even shark that the hospital buys weekly from Port Clyde Fresh Catch.

In the summer and fall, the hospital buys produce from Hatchet Cove Farm, an organic farm in Warren, and advertises that fact to patients. Pelillo estimates the hospital spends 15 percent of its food budget on local foods. “We were looking at bringing in food for the patients, giving them a nice quality product, plus we also wanted to support the local vendors,” Pelillo said. “There’s an opportunity right here in front of us, so why not use it?”

Pen Bay is one of at least 10 Maine hospitals trying to purchase ingredients from Maine farms and fishermen. These hospitals are part of a national movement aimed at improving sustainability, nutrition and community engagement by changing the way hospitals and other institutions source their food. They are following in the footsteps of schools and universities, many of which have already embraced local foods.

“I think they’re learning from the school food movement, and in some cases are enhancing what the school food environment has done,” said Jennifer Obadia, New England coordinator for Health Care Without Harm, a group that is working with an organization called Farm to Institution to increase the amount of New England-grown food in schools, hospitals and colleges. “Some people see it as an opportunity to do something bigger and rebuild the healthy and sustainable regional food system.”

Hospitals are acknowledging their position as public health role models and – in competitive markets – are looking to attract patients through better food. They’re tossing out fryolaters and banning sugary drinks in hospital cafeterias. But as they try to increase their proportion of local foods, they face two big obstacles: the higher price of local food and the lack of infrastructure to get it to hospitals in a convenient form.

Unlike restaurants, hospitals can’t just buy produce from any farmer who comes to their back door. They have to think about patients who are ill and have compromised immune systems, so any farm that works with them must be ready to provide proof they are insured and use good agricultural practices.

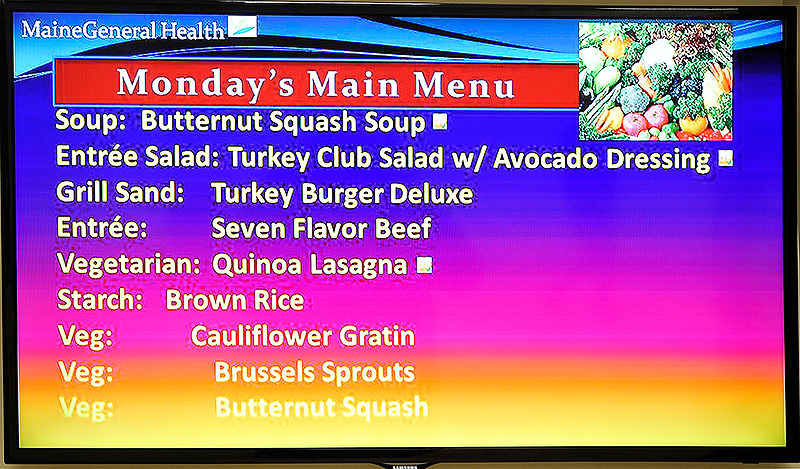

When MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta started pursuing local foods in 2010, it partnered with Barrels Community Market in Waterville, which acted as the hospital’s local foods distributor for the first couple of years. When the program outgrew Barrels, The Pickup in Skowhegan took over. The hospital now also works with Crown of Maine and Northern Girl, which cuts local carrots for patient meals and the cafeteria.

Although the amount of local foods it purchases is still small, MaineGeneral is now considered a leader in the farm-to-institution movement in Maine, at least in the hospital category. Last year, the healthcare facility spent $30,000 on 19,000 pounds of produce grown on 20 Maine farms. The first year the tab was just $10,000.

“Thirty thousand dollars is a great start,” said food services director Conrad Olin. “It sets an example for what you can do.”

Total spending on local foods at MaineGeneral last year was a more impressive $178,000 – that includes all locally sourced products, such as Poland Spring water, Grandy Oats Granola, and grass-fed beef from Sunset Meadows Farm in Vassalboro. “We also switched from buying the national brand of oatmeal to a locally grown oatmeal right out of The County,” Olin said.

Still, he points out that it remains a tiny portion of the hospital’s total $2 million food budget.

SMALLER HOSPITALS, BIG GAINS

Smaller hospitals in Maine are also paying more attention to local foods, although “It’s a little more work, especially at first, for your kitchen,” said Sheila Costello, nutrition manager at Waldo County General Hospital in Belfast, a 25-bed hospital that serves 200 lunches a day.

Farmers don’t have the time to process vegetables for hospitals, so it’s up to Costello’s 25 employees to wash the lettuce, peel the carrots and chop the potatoes.

“You’re not opening a can,” Costello said. “You’re de-stemming the green beans. You’re cutting the squash in half.”

Costello started by going out and meeting local farmers, telling them that she would commit to buying 40 pounds of vegetables from them every week, “and we can play it by ear what they are.” She even developed her own checklist to ensure that the farmers were using safe practices.

Soon she had a contract with True North Farms in Montville, and it wasn’t all tomatoes and potatoes, either.

“They grew these really small snacking peppers,” Costello said. “You didn’t have to do anything to them. You could roast them whole and they were so tender that you could just put them on the salad bar. People loved them. It was something really easy for my kitchen.”

Today Costello also gets fresh vegetables into the fall from Cross Patch Farms in Morrill. In the winter, she buys storage crops such as apples, beets, squash and potatoes from Crown of Maine. Borealis Breads makes a weekly delivery. She gets ground beef and stew beef from Goose River Farm in Swanville. Grandy Oats granola is served in the cafeteria and on the patient menu. All in all, 20 percent of the hospital’s fresh fruit and vegetables are now local.

COST-CUTTING TRICKS

“Price point is still a challenge right now,” said Obadia of Health Care Without Harm. Small local farms, she said, lack the advantages of scale of huge food service companies.

Costello has learned some things along the way about cutting costs. She tells her farmer to save the fancy greens for restaurants – she’ll take straight-up romaine, thank you very much. And when Costello instructed a farm to throw the hospital’s cherry tomatoes into a crate instead of packaging them into little boxes, the farmer gave her a price break. When it comes to regular tomatoes, she takes the seconds and turns them into soup. Olin does the same.

“When it first started, I had sticker shock,” he said. “When I can buy a case of tomatoes for $20, and then you’re buying that same case (from the farmer) for $60, I had sticker shock.”

Sometimes, he said, he’ll spend a little more on good tomatoes, knowing that the carrots he’s buying are “reasonably cheap.”

“The number I always hear is that people are willing to pay 10 to 15 percent more,” Obadia said. “If you can keep the margin within that, most institutions can work within that and feel that’s still reasonable. Above that, the budget just can’t handle it.”

The cost of buying local is highly variable from hospital to hospital, said Deborah Deatrick, senior vice president for community health at MaineHealth. In some cases, the food services director is expected to find economies of scale, as Costello has done at her hospital. In other cases, upper management might make a well-timed call to a hospital’s CEO or CFO, reminding them that although it costs more in the short term to buy local, in the end it serves the hospital’s larger mission.

Lack of infrastructure also prevents more local food from reaching Maine hospitals. Infrastructure needs range from simply peeling and cutting the tops off of carrots – more processing than most farmers or hospitals can do – to consistently supplying larger hospitals with enough food. And juggling contracts with many small farms is a lot more work for a hospital food service director than sitting at the computer and ordering everything from a single web portal. “Those sort of efficiencies we’re still trying to figure out,” Obadia said.

Maine Medical Center, which has increased its use of local foods by at least 10 percent in the past two years, would like to follow in Pen Bay’s footsteps and offer seafood from local purveyors. But food services director Kevin O’Connor isn’t sure it will be economically feasible, or practical, to do so.

Beyond the higher price of local, fish from large distributors is typically frozen and portioned, he explains, making it much easier on hospital cooks. “I think it would be very difficult to try and match that.”

As with other large institutions that have tried to switch to local buying, it gets trickier if a hospital has a relationship with a food service management company. Such arrangements typically allow hospitals to order 10 to 20 percent of their food from other sources, but any more than that, and they may be breaking their contract.

Cape Elizabeth resident Kurt Shisler is working on building a “pipeline” that will make it easier for farmers, distributors and hospitals to work together providing a more convenient and consistent supply of local food. When Shisler started his “Mainstreaming Project,” which is supported by the John Merck Fund, he spoke with 35 institutions all of which told him they’d like to be able to get local produce from a single large distributor. Last year, he selected six pilot products to start with – bulk and peeled carrots, bulk and peeled butternut squash, kale, and broccoli.

For this kind of system to work, he has learned, large distributors are going to have to “evolve their business practices,” including improving communication with farmers. “You’re not going to have farmers plants a lot of carrots unless they know they can sell them,” he said.

At the end of this pipleline are, of course, the patients and the hospital staff who eat the food. Making patients happy is good business, Deatrick said.

“Hospitals are increasingly using (food) as a way to increase their satisfaction of patients who are coming into the facility and demonstrating their commitment to good health,” she said. “They’re interested in the health of the community, as well as the local economy. For many hospitals, this has become a business strategy in addition to it being a health-promoting strategy.”

PLEASED PATIENTS

Costello says her patient satisfaction scores at Waldo General have gone up since she started serving more local food. A more tangible sign that patients are on board: the salad bar now gets refilled five times a day instead of just once.

At MaineGeneral, Conrad Olin says the increased attention to food, including adding more local food and offering room service-style meals, has lifted “mediocre” patient satisfaction scores from 65 to 70 percent into the 90th percentile nationally.

Last week, Paul Burd of Hallowell, a retired CMP employee recovering from a lung problem, ordered a chicken stir-fry that included local carrots for lunch. Burd has been in rehab for three weeks and had become known among the staff for his enthusiasm about the hospital’s food. “This is the best place in the world to eat,” he said.

But he had no idea that the oats in the oatmeal he likes for breakfast were grown in Maine, or that anything in his lunch came from a local farm.

“I’m tickled to death to hear that,” he said. “Any way an institution the size of this (one) can use local farmers, I’m all for it. Farming’s a tough business.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story