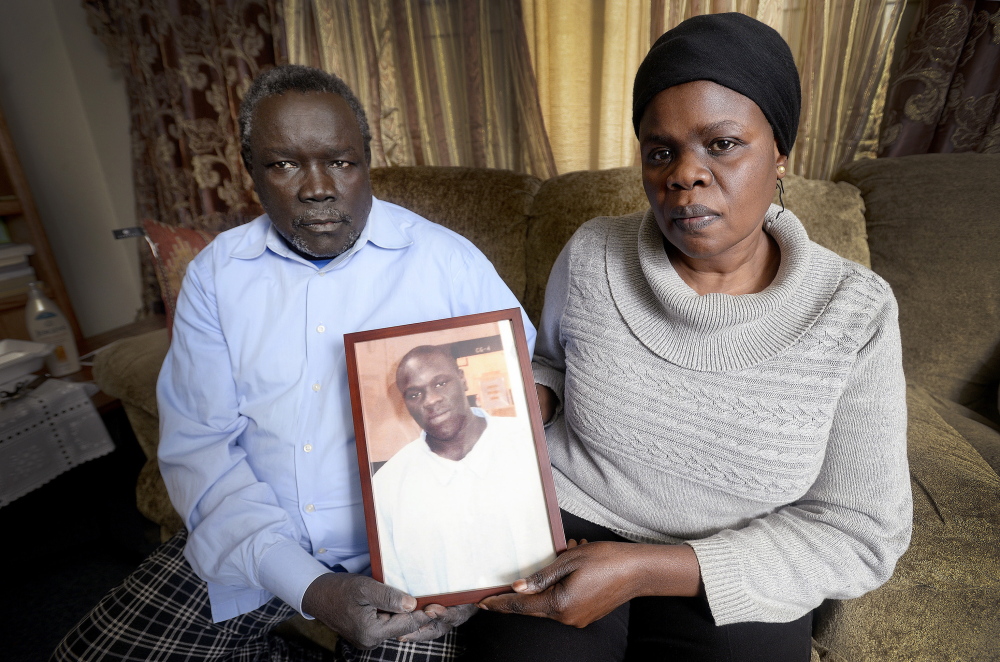

Richard Lobor’s parents came to Maine from Sudan because they wanted a better life for their children. But after 11 years in the U.S. — five of which he spent in the Maine State Prison for armed robbery — Lobor was shot and killed on Nov. 21. At the time of his death, he was just 23.

As a child in a war-torn country, Lobor was exposed early to a level of violence that can derail a young person’s development for years to come. Indeed, hundreds of thousands of other refugee children in the U.S. likely have had similar experiences. And there will be a negative impact on all of us — children, families and communities — until we as a society commit to recognizing and mitigating the impact of trauma on its young refugee victims.

The fallout from early trauma is evident in the all-too-short life story of Lobor, who came here at 12 with his family from a nation plagued by factional strife. There were clashes between Sudanese rebels and government forces; people were executed if their allegiances were in doubt.

Research has shown that refugee children come here with a lot of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder: anxiety, depression, flashbacks and an inability to concentrate. Early traumatic experiences also have been linked to school failure, drug abuse, anti-social behavior and a tendency to isolate oneself.

Lobor excelled as a student and an athlete during his early years in Maine but was a troubled teenager. And the graver consequences of childhood trauma victimization are evident from Lobor’s criminal record — his history of juvenile offenses along with the armed robbery charge on which he was tried as an adult. Youths who witness violence are more likely than others to behave aggressively, studies show. In fact, at least 75 percent of the children in the juvenile justice system have been exposed to trauma.

Intervention can and must take place before traumatized refugee children act out — though cultural and language barriers can make this difficult. Lewiston’s public schools have adopted one promising approach: Project SHIFA, which emphasizes family and refugee community involvement in the treatment of refugee children.

Under this model, refugee community agencies reach out to parents before any problems emerge, holding social events — such as a Ramadan tea — where families can hear about the importance of children’s emotional health to their success in school.

School-based youth groups allow refugee children a place to talk about what’s on their minds; because all English Language Learners are invited, no one refugee child is singled out as having “special needs.” A parent advisory council meets regularly to review the program and assess whether it’s helping their kids.

Refugee children have survived a lot in their young lives. The traumas in their past will cloud their future unless the community helps these newcomers to Maine get the services they need to build a happy, productive life here.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story