In the fall of every year, parents say goodbye to their newly adult children as they head off to college or travel overseas for “gap year” experiences. Scenes of heart-wrenching separations take place at airport terminals, bus stations and college campuses.

Or in the case of Sally Gardiner-Smith and her parents, on the fuel dock at DiMillo’s Marina on Portland’s waterfront.

The 18-year-old from Woolwich is spending her gap year sailing alone.

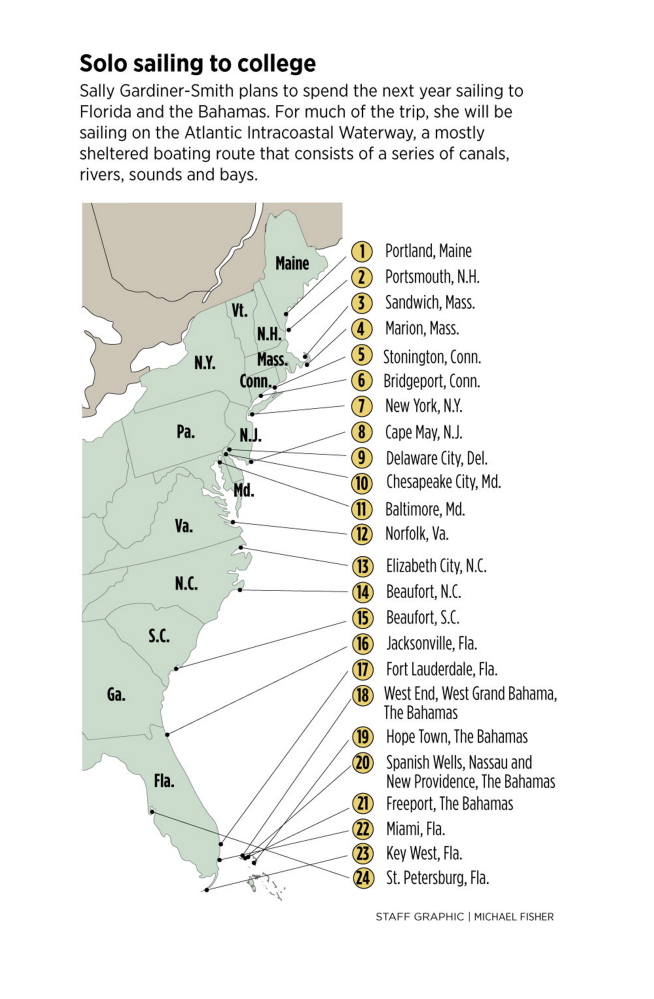

Her journey will take her down the Eastern Seaboard to Florida’s east coast, then east to the Bahamas, west to the Gulf of Mexico and on to Florida’s west coast. If all goes well, she will arrive at the docks of Eckerd College in St. Petersburg next September, in time for freshman orientation.

Sally left last Monday in a 29-foot boat, named Athena after the Greek goddess who embodies wisdom. That’s pretty much her reason for the trip, to embark on an adventure that helps her grow in confidence and maturity.

“I hope that this trip is an opportunity to solidify myself as a person through hardships and, hopefully, successes,” she wrote in her blog. “I decided to make this trip solo, not from lack of offers to accompany me as crew, but because of a desire to prove to myself that I can do what I want with my life.”

At DiMillo’s Marina, though, she seemed to have mixed feelings as she approached the time of her departure,

“I am so excited to start my own life and do my own thing,” she said. ” But I am really, really sad moving out of home. Mom won’t be there.”

Her mother, Maggie Gardiner, climbed aboard the boat and made her daughter’s bed, located in the bow, where Sally will sleep each night. Her father, Willy Ritch, spokesman for U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree, replaced a piece of the steering gear and brought a cable that will allow her iPad to be charged by the boat’s batteries.

He also gave her a USB flash drive that contains a memo to remind her to check her engine oil and coolant, and information on how to keep the battery charged and take proper care of the sails. The drive also contains photos of her when she was a child.

Not surprisingly, many of the photos were taken on the water. When Sally was born, the family was six months into a two-year sailing trip that would take them to the Bahamas and then on to the Yucatan in Mexico, Belize and Guatemala.

On the family’s second big trip, when she was between the ages of 4 and 6, they sailed across the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Sally and her older sister, Elin, went to a public school for about four months in Barcelona on that trip.

Although being alone will be the biggest challenge during her latest trip, Sally said, she remembers conquering loneliness when at age 16 she left her family in Maine and traveled to Thailand, where she studied for a year and lived with local families.

Although she plans to be alone for most of her journey, friends and family will join her from time-to-time on land near one of her anchorage stops or in the water on a leg of her journey. She also plans to make friends with sailors heading south on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, a largely sheltered boating route from Massachusetts to Florida that consists of a series of canals, rivers, sounds and bays.

Both parents said they support their daughter’s trip because she’s an experienced sailor and sensible young woman. Last summer they bought her a boat – a 43-year-old fiberglass sailing yacht called an Ericson – for $7,000, chosen for its basic design and because they figured it’s the largest boat a person could operate alone.

Sally spent the summer working at Robinhood Marine Center in Georgetown and put $1,000 in the bank. That’s the money she has available to live on for the next year.

Her plan is to pick up odd jobs among the sailing community along the way, such as babysitting and cleaning boats. To save money, she’ll anchor in harbors rather than pay to dock at a marina.

Her boat is essentially a floating cottage that will give her free access to ports all along the coast, said Alex Agnew of Falmouth, who publishes Ocean Navigator magazine for recreational sailors.

Agnew said it’s highly unusual for an 18-year-old to embark on a sailing trip alone for this long. He said he has two college-age daughters, and he would have been alarmed if one of them embarked on such a journey.

“If they had said, ‘I’d like to do that,’ I would have fallen off my chair,” Agnew said.

He said Sally can expect a fair amount of loneliness, boredom and occasional moments of terror.

“She must have a sense of freedom most kids never experience,” Agnew said.

Her course along the coast is more dangerous than sailing in the open ocean because she could run aground or collide with other vessels in the busy coastal waters, said Pete Passano of Woolwich, who sailed alone in the mid-1990s from New Zealand to Brazil. He said he never became worried when sailing until he came within 100 miles of land.

Sally’s on-board security system is her first mate, a black cockapoo named Elli, who has her own yellow life jacket. Sally has a net to fetch her out of the water if Elli falls overboard.

“I’ll be a weird dog person by the end of the trip,” she said with a laugh.

Sally has several navigation charts on her iPad, and a radio beacon that is used to alert search and rescue services in the event of an emergency. She wears a life jacket that will inflate automatically if she falls into the water.

She’ll be able to get back on the boat by climbing on the dinghy she tows behind the boat, her father said shortly before Sally departed on her trip. “If she can catch up to it,” her mother said nervously.

For her parents’ peace of mind, Sally has a DeLorme- made satellite communication device that updates her position on a website they can check. And her cellphone will work until she gets to the Bahamas.

Sally said she sometimes gets nervous about her trip, but she tries to think about it in small segments so it seems less daunting.

“I know I can pull up the anchor and sail for the day and put the anchor down again,” she said. “I know I can do that every day. I know I can do it.”

On that morning at DiMillo’s, her two aunts, Claudia and Jenny Ritch-Smith, joined Sally’s parents to see her off. As the boat moved away from the dock, Jenny Ritch-Smith shouted, “It’s OK to go …”

“If you promise to come home,” Sally shouted back, finishing the phrase, the family’s traditional saying as a member embarks on an adventure.

Everyone watched the Athena as it sailed past an oil tanker and then Fort Gorges. The boat disappeared as it rounded Spring Point and headed toward the open ocean.

“She’s gone,” her mother said.

By Sunday, Sally had made it safely to Gloucester, Massachusetts. But she had already experienced a bit of terror in Maine.

Upon entering York Harbor, she had backed over her dinghy line while trying to grab a mooring, causing the engine to stop when the line became tangled in the propeller. She said she panicked for a moment as she wondered how to keep her powerless boat from smashing into the rocks on shore, but then remembered she had an anchor and threw it overboard to prevent a grounding.

After tying up the boat at a dock, she dove into the cold water with a knife to cut the line free from the propeller.

Later, as she sat shivering in all her blankets, she remembered that her father had warned her of cascading failures – when a small problem leads to other problems and eventually disaster.

“It was a mistake, definitely, but more so it was a learning experience,” she wrote in her blog that night. “There will be many, many more learning experiences before I reach the crystal-clear waters of the Bahamas. And probably some there as well.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story