This year marks the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s speech announcing plans to send Americans to the moon — and marks the end of the space shuttle program.

Today, many Americans have no memory of the moon landing, and NASA isn’t a source of pride but a budget line that needs to be cut. Why spend billions exploring an uninhabitable environment when many Americans don’t have health care? To understand the importance of our space program, it’s first necessary to debunk some misconceptions about what NASA is and how it operates.

1. NASA’s purpose is to colonize space.

Founded in 1958, a year after the Soviet Union put Sputnik in orbit, NASA was never intended to open space to settlement in the same way the Transcontinental Railroad had helped open the American West to pioneers. U.S. foreign policy, not science fiction dreams of cities on the moon, drove the agency.

In contrast to the Soviets’ militarized efforts, President Dwight Eisenhower wanted a peaceful space program that would demonstrate American moral superiority. This civilian agency would be a key part of America’s Cold War strategy. When Kennedy set his eyes on the moon 50 years ago, he asked his science advisers for an initiative “in which we could win.” When Ronald Reagan kicked off the space station program in 1984, his motivations weren’t much different. “We are first; we are the best; and we are so because we’re free,” he said.

Even after the Cold War, the Clinton administration recast human spaceflight as a means of turning Russia’s aerospace industry toward peaceful purposes and validating Russia’s entry into the community of Western dem-ocracies. The idea that the U.S. government would spend billions colonizing the solar system reflects the cultural impact of “Star Trek,” not reality.

2. NASA is extraordinarily expensive.

At the height of the Apollo program, NASA consumed more than 4 percent of the federal budget. In the 1960s, that was a lot of money. Today, it’s a rounding error. NASA’s budget for fiscal year 2011 is roughly $18.5 billion — 0.5 percent of a $3.7 trillion federal budget. In 2010, Americans spent about as much on pet food.

And those who complain that it is a waste to spend money in space forget that NASA creates jobs. According to the agency, it employs roughly 19,000 civil servants and 40,000 contractors in and around its 10 centers. In the San Francisco Bay area alone, the agency says it created 5,300 jobs and $877 million worth of economic activity in 2009. Ohio, a state hard-hit by the Great Recession that is home to NASA’s Plum Brook Research Station and Glenn Research Center, can’t lose nearly 7,000 jobs threatened by NASA cuts.

Even more people have space-related jobs outside the agency. According to the Colorado Space Coalition, for example, more than 163,000 Coloradans work in the space industry. Though some build rockets for NASA, none shows up in the agency’s job data.

3. NASA’s research is useful only in space.

Had a breast exam lately? Algorithms developed for the Hubble Space Telescope improved image processing in mammography. Been caught in a natural disaster? NASA advances in deployable radio antennae helped secure emergency communications after Hurricane Katrina and the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Fighting the war on terror? Miniaturized sensors that sniff the air for traces of life on other planets led to the development of easy-to-use, hand-held devices to detect explosives and chemical agents on this one. NASA technology often finds a way back to Earth.

But high-tech spinoffs are not the primary reason to explore space. NASA advances human knowledge.

Its Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, recently affixed to the space station, will help answer questions about the total of all matter and offer new insights into the origins and nature of the universe. Hubble has already furthered our understanding of the big bang, black holes, neutrinos and dark energy — issues at the heart of physics and mathematics.

Since space missions rely heavily on solar power, NASA is always searching for ways to improve solar cells and batteries and may one day help cure America of its oil addiction. These developments would not appear on NASA’s cost-benefit balance sheet, but they are no less valuable to society.

4. NASA is an obstacle to private enterprise in space.

In a recent debate, GOP presidential candidate Newt Gingrich said that “NASA ought to be getting out of the way and encouraging the private sector.” In truth, NASA is not an obstacle to the free market. The agency does not prohibit space entrepreneurs from starting businesses. Where a demand for goods and services exists in the space industry — principally in telecommunications, but perhaps soon in suborbital human spaceflight — firms such as the space-transport company Virgin Galactic are trying to provide them.

The bulk of NASA’s missions are not commercially viable and are unlikely ever to be. There is not enough demand for robotic missions to Mars, Hubble Space Telescopes and Alpha Magnetic Spectrometers to justify private investment. If NASA worked the way policymakers such as Gingrich want it to — paradoxically “getting out of the way” while providing venture capitalists government money to start space businesses — the agency could actually hurt private enterprise in space. NASA would not be better at picking commercial winners and losers than the rest of the government. By making poor or even politically motivated choices, it could spoil a free market.

5. The American space program still leads the world.

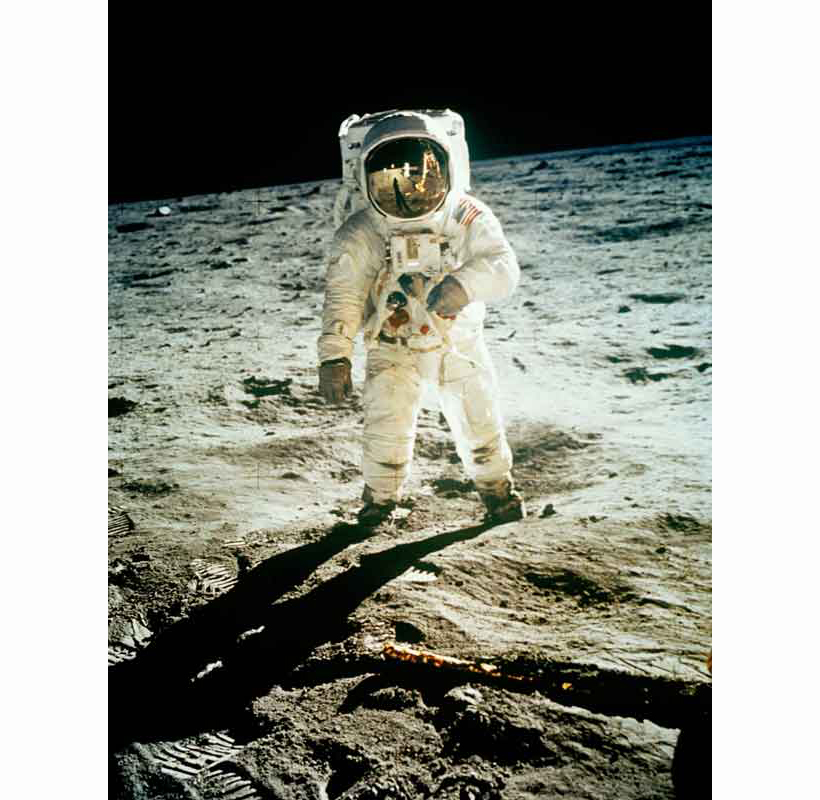

For most of the Cold War, NASA sought and secured partnerships with foreign space powers. Still, the United States — the only country to put a man on the moon — was first among equals because of its size and experience. NASA set the pace for humanity’s exploration of space.

Those days are over. Nine countries, including India, Israel and Iran, have placed payloads in orbit. More than 50 nations design, deploy, own or operate satellites without U.S. involvement. China and Brazil, for example, have been co-developing Earth observation satellites for years. Japan and China have mapped the moon in considerable detail. India launched its own robotic moon mission in 2008, with a planned follow-up mission in cooperation with Russia. The United States may still have the largest, most ambitious civil program in the world, but it no longer solely charts the world’s future in space.

NASA is in the midst of considerable turmoil. Congress and the agency do not agree on the feasibility of its flagship human spaceflight program, and the president’s direction is vague and under-resourced. Will we go to Mars? Return to the moon? Visit an asteroid? Policymakers haven’t definitively answered any of these questions. To get ahead of the pack, mission control in Washington will need a clearer sense of its mission.

Eric Sterner is a fellow at the George C. Marshall Institute in Arlington, Va., and NASA’s former associate deputy administrator for policy and planning. This column was distributed by The Washington Post, where it first appeared.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story