WASHINGTON — For months, the White House made highly unusual releases of intelligence findings about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s plans to attack Ukraine. Hoping to preempt an invasion, it released details of Russian troop buildups and warned repeatedly that a major assault was imminent.

In the end, Putin attacked anyway.

Critics of U.S. intelligence — including Russian officials who dismissed invasion allegations as fantasy — had been pointing to past failures like the false identification of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. But Russia’s invasion so far has played out largely as the Biden administration said it would back in December, with nearly 200,000 troops striking from several sides of Ukraine.

Lawmakers from both political parties on Thursday said the accurate predictions were a credit to the often-criticized U.S. intelligence community.

But whether the White House’s unprecedented public campaign delayed or limited Putin’s plans could be debated for years. And some say both Washington and Kyiv could have done more with the information the two governments had beforehand.

Ukrainians are fighting a vastly more powerful Russian army all over their country, with deaths reported on both sides and explosions in several cities. There are fears Russia may try to depose Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, even as Putin claims — in the face of the U.S. intelligence — that Russia is only trying to protect residents of two separatist territories in eastern Ukraine.

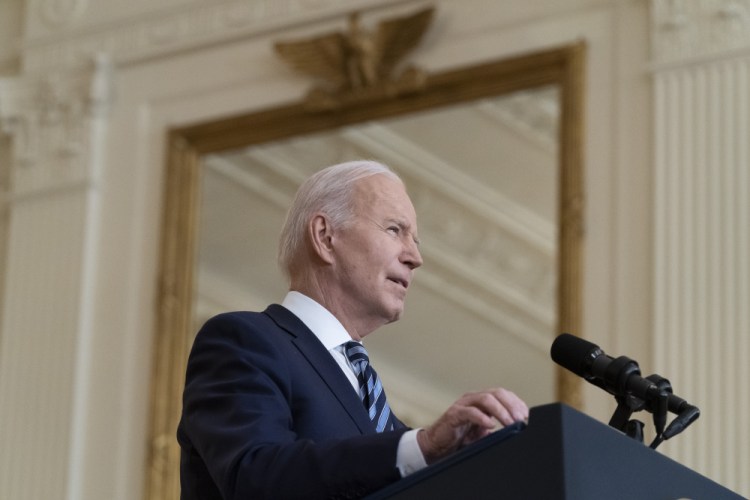

Announcing new sanctions on Thursday, President Biden cited his administration’s moves to warn of what it knew of Putin’s intentions.

“We shared declassified evidence about Russia’s plans and false pretext so that there could be no confusion or cover-up about what Putin’s doing,” he said. “Putin is the aggressor. Putin chose this war. And now he and his country will bear the consequences.”

Sen. Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat who chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee, noted several results of the public campaign: weakening any potential move by Putin to create a “false-flag” operation to justify war, undercutting any potential coup in Kyiv that might have appeared to be led by Ukrainians, and unifying allies who quickly denounced Putin’s aggression this week and backed tough sanctions.

“The intelligence community usually doesn’t like to share information; they want to hold it close,” Warner said in an interview. “What they’ve done is push the Russian timeline back. They’ve also, I think, allowed us to build this coalition that is virtually unprecedented.”

Ohio Rep. Mike Turner, the top Republican on the House Intelligence Committee, said the Biden administration’s declassifying of information was “incredibly important.”

“This has both impacted the international community’s view of Putin and has slowed his actions,” Turner said. “The goal in releasing intelligence is to permit Ukraine to plan, and any delay in Putin’s actions helped Ukraine in the planning to defend itself.”

But Turner said the White House should have provided more lethal weapons and air defense capability to Ukraine in advance. He also said that the White House was initially reluctant to provide some of its intelligence findings to Kyiv.

One U.S. official familiar with the intelligence gathering, who was not authorized to comment publicly by name, said the White House shared intelligence with Ukraine about Russia even before the troop buildup began last year and accelerated its sharing throughout the crisis. The official added that the administration reduced constraints to allow findings to be shared with the Ukrainians and more broadly with allies.

Still, Washington and Kyiv were often publicly and privately at odds about the nature of the Russian threat and what needed to be done.

Zelenskyy for months tried to publicly downplay American warnings of an imminent major outbreak, noting that Ukraine remained locked in an eight-year war over the eastern Donbas region fighting Russian-backed separatists. Zelenskyy did not call up military reservists until Wednesday, when he also announced a 30-day state of emergency.

“The one area that I wish we could have been more effective is convincing the Ukrainians themselves to further mobilize their troops, their reserves,” Warner said Thursday. “I’m not saying that would have stopped the Russian invasion. The Russian forces are so overwhelming. But it might have allowed a bit of a better fight.”

A Ukrainian government official who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence said Kyiv was convinced about two weeks ago that Russia would invade. But the government publicly tamped down concerns about an invasion to limit damage to Ukraine’s economy and panic in the country, the official said. Any mass mobilization of Ukrainian forces could have given additional pretext to Putin, who repeatedly and falsely claimed Ukraine was planning to attack separatist-held parts of the Donbas.

The official also noted that only on Wednesday did the U.S. sanction the company that built the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. Zelenskyy and lawmakers from both parties had long pushed for the sanctions on the pipeline, which would carry natural gas from Russia to Germany and bypass Ukraine.

“We wish it were a deterrence victory, not an intelligence victory,” the official said. “Unfortunately there was zero deterrence and now we have a humanitarian catastrophe.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story