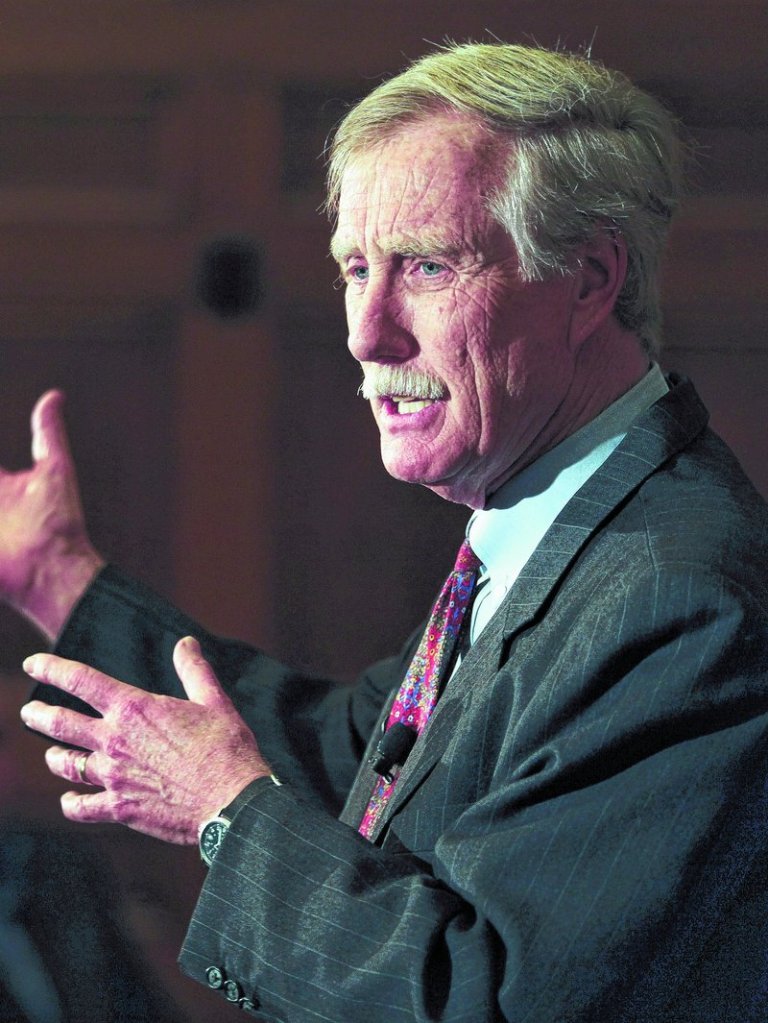

Former Gov. Angus King defended himself Tuesday against accusations that his involvement with a federally monitored Portland bank shows he has a history of fiscal mismanagement.

The Maine Republican Party issued a statement late Monday noting that King served on the board of directors of The Bank of Maine, which has operated under a federal compliance order since shortly after King’s departure this spring.

In an interview Tuesday, King said he was part of a turnaround effort by the bank before he stepped down from its board to run for the U.S. Senate.

“This was a Maine institution with 330 jobs that was about to go under,” said King, who is running as an independent.

King is the front-runner in the race for Maine’s open Senate seat, and Republicans hope to create an opening for the GOP nominee, Charlie Summers.

The party issued a second release late Tuesday, suggesting that King’s departure from the board of a Bermuda-based investment company in 2010 is another example of his poor financial record.

The Maine Republican Party’s latest criticism of King is intended to build on the message of a recent $400,000 television ad campaign by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that called him “the King of mismanagement” for his handling of the state budget as governor.

“He’s a nice guy, I’m sure. But he just has a real history of fiscal mismanagement, and Maine needs results, not another nice guy,” said David Sorenson, communications director for the Maine Republican Party.

King, who has defended his record of budget management as governor, spoke at length Tuesday about his time on the board of The Bank of Maine, from September 2010 to March 2012. He was paid $66,750 to serve as a director between January 2011 and the time he left the post in March, according to his financial disclosure report.

Federal regulators uncovered financial problems in 2009, when it was still called the Savings Bank of Maine. The bank was having difficulty covering loan losses because of poor loan decisions and the downturn in the economy, according to news reports at the time and the current CEO.

The federal Office of Thrift Supervision issued a cease-and-desist order, restricting the bank’s lending and setting deadlines for it to boost cash reserves to cover its problem loans. The order, which was amended in March 2010, said the bank could be forced to sell its assets if it didn’t increase cash holdings.

John Everets, the current chairman and CEO, led a recapitalization in May 2010, investing $60 million and keeping the bank in business.

Everets and partners brought in a new management team and a new board of directors that included top executives in finance and some Maine business experts. Everets said he recruited King, who built and sold an energy business before becoming governor, because of his knowledge of the state and his business relationships.

“He brought a lot of business savvy to the bank. We miss him,” Everets said.

The recapitalization and efforts to shed problem loans eased the concerns of federal regulators, who lifted the bank’s business restrictions in January 2011. The bank began building a new loan portfolio, while gradually removing problem assets, Everets said.

The bank got another regulatory review in the summer of 2011, by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which has been imposing a new regime of banking rules as part of the so-called Dodd-Frank Wall Street reforms.

Regulators identified problem loans remaining on the bank’s books, and the need for new compliance controls. The concerns were discussed by Everets and board members, including King, last summer and fall. King and Everets said the bank moved quickly to address the regulators’ concerns.

“It was mostly things that everybody knew,” King said Tuesday. “I think the assumption was the turnaround would be faster.”

King resigned from the board in March, soon after announcing he would run for the Senate. He said he did not want to give the appearance of a conflict of interest if someone who got a loan from the bank then donated to his campaign.

In May, the company’s remaining directors signed a Formal Agreement based on the 2011 exam and set new deadlines for the bank to implement a list of new compliance measures, such as forming a compliance committee and a risk reduction plan.

The Formal Agreement says “the Comptroller has found unsafe and unsound banking practices and regulatory violations,” and the bank was being designated in “troubled condition.”

Sorenson, with the Maine Republican Party, said the order shows that King’s efforts on the board didn’t help.

“I think it’s clear the problems at the bank were not cleared up during Angus’ time there, and this is another example in a clear pattern of mismanagement,” he said Tuesday.

King, meanwhile, said the company is still in the midst of a turnaround and he’s glad to have contributed in a small way.

“The problems with the bank predate the current management, and what they’ve been doing for two years is righting the ship,” he said. “This was a case of stepping in to save 300-plus Maine jobs, and it looks good.”

Everets said the bank is still gradually removing old problem loans and has built a new $200 million loan portfolio that is solid. The bank now has $80 million in cash reserves and $120 million in other liquidity, he said.

A review of balance sheets shows the bank’s assets have shrunk from $890 million in 2008 to $775 million this year, and that cash reserves have increased dramatically. “It’s a great balance sheet now,” Everets said.

He said the transition to new federal regulations under Dodd-Frank means compliance agreements are becoming more common.

Formal Agreements are the most common form of compliance orders, and are much less severe than cease-and-desist orders. Eighty-five banks nationwide have been issued Formal Agreements this year, including one other bank in Maine, Auburn Savings Bank.

The existence of a Formal Agreement means regulators have compliance concerns, but it doesn’t necessarily signify financial mismanagement or risk of a bank failure, said Gretchen Jones, a lawyer who represents banks but has no connection to The Bank of Maine.

“In 20-something years, I think I can fairly say I have never seen an examination that doesn’t result in a (signed memorandum or letter),” she said. “Generally, the regulators will come in and they will manage to find something that isn’t done to their satisfaction.”

Jones said descriptions like “unsound” or “troubled condition” are routine legal terms that allow regulators to set compliance deadlines. “That’s how they wield the hammer,” she said.

The King campaign responded late Tuesday to the latest criticism from the Maine Republican Party, about his departure in 2010 from the board of W.P. Stewart & Co. Ltd., a Bermuda-based investment company.

The GOP said it didn’t have details about King’s role there, but that King left after the stock slid and during a takeover that led to a corporate turnaround.

King said through a spokeswoman that he simply left the board when a new owner came in and brought in his own board members.

King also said Tuesday that it doesn’t make sense to hold board members responsible for every up or down in the business world.

“I’m also on the board of Lee Auto, and they had one of the best years in their history last year,” King said. “Does that make me a financial genius?”

Charlie Summers’ campaign manager, Lance Dutson, said Tuesday that he didn’t know enough details about King’s corporate board activities to comment on the GOP’s criticisms.

“The one thing that we are very familiar with is his financial mismanagement of state government,” Dutson said.

Staff Writer John Richardson can be contacted at 791-6324 or at:

jrichardson@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story