If you have a clear view of the western horizon, you might be able to catch a glimpse of Jupiter shining bright in the evening these days.

Using binoculars in a clear, dark sky after sunset, you might be able to pick out two or three or all four of its biggest moons, which will look like tiny pinpricks of light.

They astonished Galileo when he aimed one of the first telescopes at the sky about 400 years ago and spotted them.

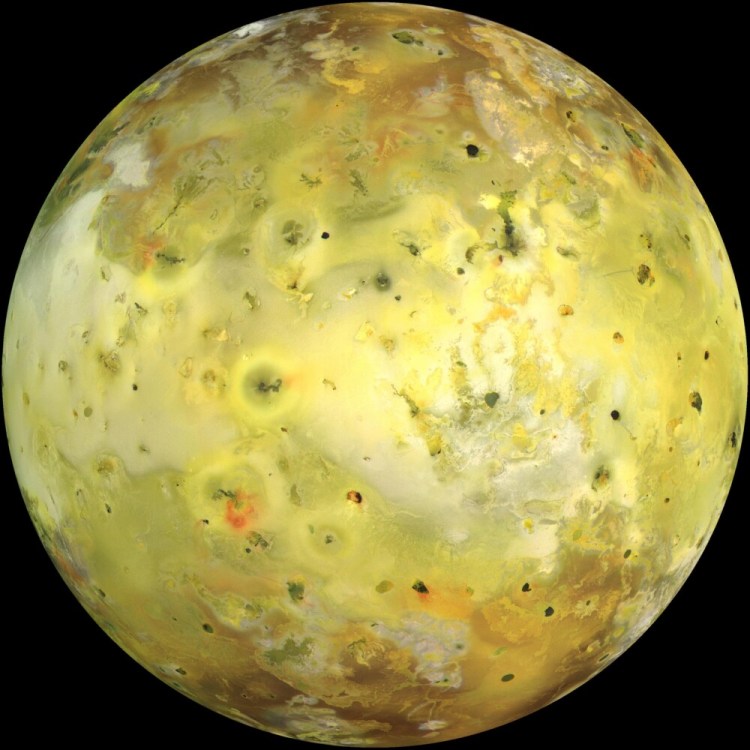

Astronomers debated for centuries what goes on among them, until robots got there in recent decades to sort things out. All four of Jupiter’s large moons are kind of weird, from a terrestrial perspective. But looking with a certain kind of eye at images of one of them, Io, can make you cringe.

It is a seething waste land. Sulfurous, flaky yellow sands stretch across distances cracked by miles-wide gouges, while 10,000-foot mountains jut up like inverted chasms, and pools of lava heave from gashes in the surface like massive boils. Volcanoes shoot ash and gas hundreds of feet into emptiness.

If somehow you could stand on Io’s disturbed surface, you would see Jupiter crawling like a gargantua across the sky, a bright, vast, streaked disk eating the blackness of space, obliterating stars, and so huge it seems intent on crushing everything under it. It overwhelms the sky and could outright terrify you, like the man who was fool enough to demand to see an angel’s real face.

But worse than what you can see, is what you cannot see. Except for these glimpses snatched by robot cameras of blistered yellow-orange flatness, reddish lava, puking volcanoes and fang-shaped mountains, most of what happens on Io is invisible to your eyes.

Io is twisting and writhing. Every 42 hours — the period of one Ioic day — it whips around Jupiter inside the orbits of its sister moons Europa and Callisto and brother Ganymede, which is larger than Mercury.

The tugging and jostling of their gravitation and motion, and Jupiter’s stupendous gravity twisting on Io’s elliptical orbit, and its own frantic tear around the giant planet, all wobble and squeeze Io out of round by as much as 300 feet.

The surface stretches and buckles like a crushed lemon. Inside, the warping generates heat that liquefies rock. We see only the fissures that burst open like running sores.

We see Io’s volcanoes throw up gases, but we do not see them intermingle with Jupiter’s magnetosphere, a plasma of atomic particles formed from the interaction of the planet’s magnetic field with gusts of particles flowing from the sun.

The plasma corotates with Jupiter and sets up an electric current. If Io’s inside spins the way astronomers think it does, then it too has a magnetic field that interacts with Jupiter’s, and the two planetary dynamos generate perpetual electrocution. A torus of intense radiation swarms the general vicinity of Jupiter, and Io bakes in fire unknown to human flesh.

Most of this is invisible to the cameras, and yet real enough to astronomers, who attach numbers to what little the spacecraft detects. In fact, 96% of the material in the universe is beyond our perception, but we know it is there by the numbers.

The numbers themselves are never seen. They exist only in the mind, and only their expressions are actually visible. Those magnetic fields half-a-billion miles away are known to exist by equations built from measurements.

It seems almost impossible to look at pictures of Io and not see, in your mind’s eye, hell. This is an expression of an ancient psychology: What is seen, combined with what is imagined, is an equation for what is real.

No scientist or anyone I know believes Io is literally hell. But still there exists a deep intuition of suffering so intense it is barely separable from terror, as expressed in images from Dante’s Inferno, or Buddhism’s Avici hell, or Islam’s Jahannam. Io’s pits for all the world resemble those undiscovered countries, and they are disturbing.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. You can contact him at naturalist1@dwildepress.net. His book “Winter: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods” is available from North Country Press. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story