The Portland Museum of Art has received a collection of more than 600 photographs, including works by world-famous 20th-century photographers, that the museum believes will transform it into a destination for the art form.

The gift from photographer, philanthropist and collector Judy Glickman Lauder includes photographs by Berenice Abbott, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Margaret Bourke-White and Gordon Parks.

“This collection puts us at another level,” said Mark Bessire, museum director. “We’ve always done (photography), but this just leverages the work we are doing and lets us take off. This (collection) could have gone anywhere, but it’s coming here.”

Glickman Lauder, who could not be reached for an interview, has homes in Cape Elizabeth and on Great Diamond Island and a longstanding affiliation with Rockport’s Maine Media Workshops. She serves on the museum’s board of trustees and is a well-known photographer in her own right, with work hanging in prominent museums around the world, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

She is giving the PMA the collection, which includes some of her own work, as a “promised gift,” which means a pledged donation at some specified future date, although the museum already has the collection on site. The museum declined to say how much it is worth.

Libby Bischof, a history professor at the University of Southern Maine who specializes in the history of photography and has co-authored a book on Maine photography, was excited to learn about the donation last week.

“Six hundred photographs from artists of this caliber will be incredibly important not just to the museum but to the state,” said Bischof, who happened to be sitting in USM’s Glickman Family Library, named for a previous donation of more than $1 million from Glickman Lauder and her late husband, Albert Glickman. (Several years after Glickman died, she married Leonard Lauder, also a philanthropist and art collector.)

The fact that Glickman Lauder and others, like Maine art patrons Paula and Peter Lunder, chose “to situate their significant personal collections of deeply important and impactful work in a state that’s meant so much to them and so much to American art signals to other patrons, collectors and practitioners that Maine is a place where their work can also live,” said Bischof, who also serves as executive director of the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education at USM. “It really seeds that work and Maine’s continued importance in American photography.”

The museum sees the collection, along with an eventual expanded campus thanks to its purchase of the former Children’s Museum & Theatre of Maine, as key to its future growth.

“Glickman Lauder’s gift enables the museum to think broadly about the next chapter of PMA history, specifically about how we can create open experiences with art, grow and diversify our collection, and open new and dynamic community-centered spaces that welcome our myriad communities,” museum spokesman Graeme Kennedy wrote in an email.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER’S EYE

Museum visitors will have a chance to see a selection of the photographs in October, when the museum is scheduled to mount a major exhibition, “Presence: Photographs from the Judy Glickman Lauder Collection.” It previously showed some of these works about a dozen years ago, Bessire said, but since then the collection has “probably doubled in size, and it’s still growing.”

The exhibition will be curated by Anjuli Lebowitz, the museum’s newly hired, inaugural Judy Glickman Lauder Associate Curator of Photography.

Anjuli Lebowitz, the new Judy Glickman Lauder Associate Curator of Photography, shown at her home, says, “For a long time, the verdict was that photography was not art,” but Glickman Lauder wasn’t concerned with that debate. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Glickman Lauder began collecting photographs in the 1970s, Lebowitz said, a time when the market for photos was exploding as collectors endeavored to create a respected discipline.

“Matching photos to certain artistic movements was a major theme at the time because they were trying to justify photography as art. Because of its mechanical nature, with photography, there was always a huge hang-up about whether or not it could be art,” Lebowitz explained. “For a long time, the verdict was that photography was not art.”

One of the things Lebowitz finds so compelling about this collection is that Glickman Lauder wasn’t concerned with that debate. Many collectors at the time were looking only for the “best” pictures, Lebowitz said.

“Judy is also looking for ‘What are the best pictures?’ but she is also looking for pictures that move her. She is not looking to fill in gaps – ‘I need one picture from this artist and one picture from this movement’ – that’s not the concern. Still, she has amazing pictures that are part of the canon, but she included them because they move her, because she connects to them, and I think that’s a really unique approach to forming a large collection like this,” Lebowitz said.

Bessire underlined that point.

“One of the most exciting things for us is that she is a photographer herself,” he said about Glickman Lauder. “It’s interesting to see what someone behind the lens collects. A photographer brings to collecting a different eye and a different way of looking at photography. Her eye goes to images. She’s very democratic in her choices. Just because someone is not well known doesn’t mean it’s not a beautiful image.”

The collection encompasses works “by critical contributors to the medium’s history” whose names are less familiar to the general public, such as Graciela Iturbide, Lotte Jacobi, Alma Lavenson and Ben Shahn, the museum said in a news release.

Maine Media Workshops + College President Mark Mansfield described those and other photographers featured in the collection as “the canon of photographic history.”

THE COLLECTION’S SCOPE

Bessire said the collection centers on images shot by pioneering female photographers, images of American civil rights struggles, photographs of the fashion and celebrity worlds and photographs that depict the legacy of the Holocaust and of war. (Glickman Lauder is known for her own book, “Beyond the Shadows,” featuring photographs she shot over three decades of concentration camps, camp survivors and the Danes who risked their lives to save Danish Jews during World War II.)

Irving Bennett Ellis, father of philanthropist and collector Judy Glickman Lauder, made this 9- by-7-inch, double-exposure gelatin silver print of Glickman Lauder’s mother, Louise Ellis, circa 1936. It is part of the Judy Glickman Lauder Collection. Image courtesy of Luc Demers

In a release announcing the gift, the museum included several photos that “really demonstrate the strength of the collection,” Lebowitz said. One shows a double exposure of Glickman Lauder’s mother, Louise Ellis, that was shot by her father, Irving Bennett Ellis, a doctor and a famous photographer himself. Lebowitz described it as an “incredible composite portrait showing different psychological states of Louise Ellis.”

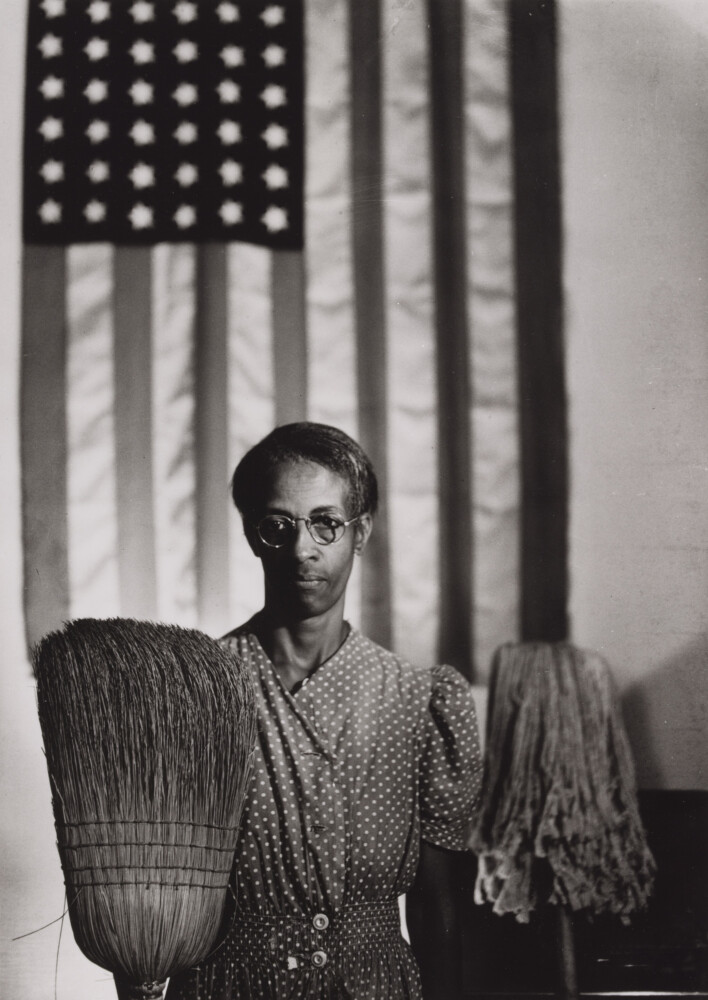

Another is “American Gothic,” a photograph by the celebrated African American photographer and film director Gordon Parks. It depicts Ella Watson, a charwoman at the federal Farm Security Administration office where Parks was working at the time, in a pose modeled after the Grant Wood painting of the same name. Instead of a pitchfork, Watson is shown with a mop and a broom; instead of a farmhouse in the background, there is an American flag.

“Judy has a very strong social justice streak, and that picture is so famous and so incredible and by one of the most important photographers of the 20th century, but I also love that it was a collaboration with the subject, Ella Watson,” Lebowitz said. It’s one of a series of nearly 100 prints that Parks made with Watson. “And it so succinctly makes the point that we as a country can do better. It shows both love of country and a rightful criticism as well,” she said.

Photographed by Richard Avedon, Audrey Hepburn and Art Buchwald, with Simone D’Aillencourt, Frederick Eberstadt, Barbara Mullen and Dr. Reginald Kernan, at Maxim’s in Paris in August 1959. A gelatin silver print, 19½ by 29 inches. “Talk about a photograph with wow power,” said Portland Museum of Art Director Mark Bessire. Richard Avedon

A third, by fashion photographer Richard Avedon, is shot at Maxim’s in Paris and shows actress Audrey Hepburn and humorist Art Buchwald.

“I think it really captures the spirit of the collector, as (Glickman Lauder) is pretty exuberant and fun as well,” Lebowitz said. “The presence of joy and wonder is really why the collection is so special, and why I’m so happy it’s here and that I’ve come to Portland to work with it.”

Lebowitz has worked in such big city museums as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. A collection like that of Glickman Lauder has a much bigger impact on a smaller institution, she said.

“Even 600 photographs can be swallowed up when you are talking about a larger place that has 50,000 photos. Here it can have pride of place,” she said. “It really is the star of the show.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story