To most casual observers, Beech Ridge Motor Speedway is a property in transition. Long a hub for racing enthusiasts all over southern Maine and beyond, the 55-acre site in Scarborough is being sold to developers who look beyond the oily pit area, the rubber-streaked asphalt and weather-worn grandstands and envision a sprawling new commerce center.

Not so for members of Save Beech Ridge Speedway. When they look out forlornly over their now-shuttered racetrack, they see dead people.

“There’s the turn four light post on the infield,” Denise Hamilton said. “There’s two locations under the grandstands where specific fans sat. And there’s one in the pits. There’s several in the infield of the track – that’s where a majority of them are.”

Apparitions? Not exactly.

We’re talking human ashes. Actual cremains of racers, track workers and fans so enamored with the 72-year-old speedway that they asked for and received permission to have small mounds of themselves buried there when they passed – a ticket, however symbolic, to the ear-splitting, earth-shaking action for all of eternity.

Or so they thought.

Emotions remain raw from the evening last September when track owner Andy Cusack let the air out of the end-of-season awards ceremony by announcing he was selling Beech Ridge and that almost three quarters of a century of racing there soon would come to an end.

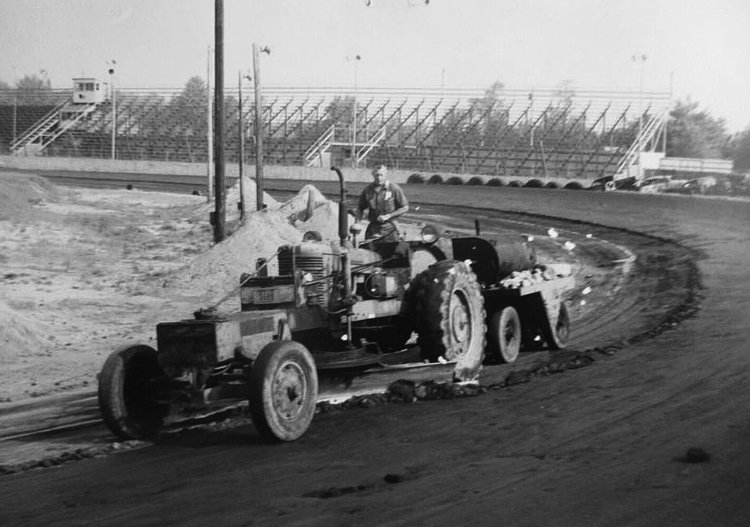

The news came as a gut punch to generations of racing families, all of whom knew the track was struggling financially. Still, they couldn’t imagine life without the place they’d long gathered on Thursday evenings and weekends to watch their local heroes circle the 1/3-mile oval bumper-to-bumper amid the screeching of tires and the guttural roar of finely tuned engines.

J.B. McConnell, who built Beech Ridge Motor Speedway back in 1949. His ashes were buried out by the track scoreboard after he died in 2008.

Hamilton, who organized Save Beech Ridge Speedway shortly after Cusack’s announcement, is one of those die-hards. She comes from a racing family and now lives adjacent to the track on Two Rod Road. Her husband, Warren Hamilton Jr., literally grew up at the track. His father, Warren “Wardie” Hamilton Sr., spent much of his life running the enterprise alongside Jim “J.B.” McConnell, Wardie’s father-in-law and Warren Jr.’s grandfather, who actually built the place way back in 1949 and owned it for more than two decades.

When J.B. died at age 96 in 2008, his ashes were buried out under the track scoreboard. When son-in-law Wardie died five years later, his ashes were interred right next to J.B.’s.

Then there’s longtime racer and track official Cliff Wescott, whose ashes are out by the scoreboard next to Wardie and J.B. There’s Leonard and Laura May, Cliff’s in-laws, who worked at the track for years and had their ashes buried under the grandstand near turn one. There’s longtime driver Sonny Butler, whose cremains lie under the main grandstand near turn four…

The list goes on. Hamilton, using a map of the property submitted to the town last month by a representative of the developers, has pinpointed 15 locations where ashes are known to have been buried. None of the cremains, as far as Hamilton knows, are in containers. And beyond her makeshift map, no spot is marked.

“From what we were told, it doesn’t matter if there’s a container or not,” Hamilton said. By law, she maintains, cremains cannot be disturbed.

Track owner Cusack’s family bought the place in 1981 from Calvin Reynolds, who’d bought it on a handshake from J.B. McConnell in 1973. Upon deciding last summer to pull the plug on the operation, Cusack put the property under contract with Scarborough Property LLC, an offshoot of Massachusetts-based Eastern Retail Properties.

Phone and email messages seeking more details from the company went unanswered last week, but an online listing produced by Eastern Retail Properties and obtained by the Hamiltons shows conceptual plans for what’s been dubbed the Scarborough Commerce Center – a 100,000-to-700,000-square-foot facility sited smack dab on top of what is now the track, grandstands and pit area.

In an interview Friday, Cusack confirmed that he gave permission for various families to bury ashes around the racetrack over the years and remains proud that Beech Ridge meant that much to them.

“I can appreciate everybody’s passion,” Cusack said. “And there’s really nobody more passionate about that place over the last 40 years or so that (his family) owned it than me.”

That said, Cusack noted, there was never any guarantee that the track – ashes included – “will always be there forever.”

Which brings us to Maine Revised Statutes Title 13, Chapter 83, Section 1371-A: “Limitations on construction and excavation near burial sites.” It states that “construction or excavation may not be conducted within 25 feet of a known burial site … whether or not the burial site…is properly recorded in the deed to the property.”

Warren Hamilton, Jr., and Denise Hamilton are leading an effort to save Beech Ridge Motor Speedway. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

The Hamiltons have hired Portland attorney Elliott Teel to see whether the planned development might run afoul of that law. Teel said he’s only begun researching the issue, but “from my look at the statute they have a reasonable claim and the developer is going to need to work around them.”

Maybe, maybe not. Under a subsection titled “Applications,” the statute also says, “This section applies only to burial sites…containing the bodies of humans.”

Underlying all of this, of course, is the grief still gripping the Hamiltons and the rest of the Beech Ridge Motor Speedway community over the loss not only of Maine’s only NASCAR-sanctioned racetrack but also a way of life that drew them together for decades and now, just like that, is gone.

“Unfortunately, greed is getting the better part of this,” Hamilton said, referring to track owner Cusack, with whom she’s so angry that she avoids mentioning him by name. “There is a buyer or two out there who wants to come in and keep this a racetrack.”

Cusack countered that he gave one such party until late October to present him with an offer, telling them “you can have a place in line if (the Scarborough Properties LLC deal) doesn’t work.”

“But guess what,” he said. “Nobody has shown up.”

It’s hard to say, as the developer’s plan winds its way through municipal and state regulatory processes, what will become of this tug-of-war between future and past. There’s talk of some kind of memorial on the site – something Cusack said he’d readily support – acknowledging not only that people once raced here, but some still rest here.

But that won’t bring the cars back. Or the fried dough. Or the blaring loudspeaker and the occasional crunch of metal on metal followed by cheers, boos and everything in between. Nor will a memorial lessen the trauma of seeing a gargantuan building atop so many places of final repose.

“If any of us knew it would not remain a racetrack, we would never have buried our loved ones’ ashes there knowing they’d be dug up and hauled away,” Hamilton said. “We do not want the ashes disturbed.”

And if they ultimately are?

Promised Hamilton, “J.B. will come haunt them for the rest of their life.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story