As a genetic researcher, Ryan Tewhey is used to waiting a decade or more before learning if his work has any practical application.

That timeline has been sped up a bit lately.

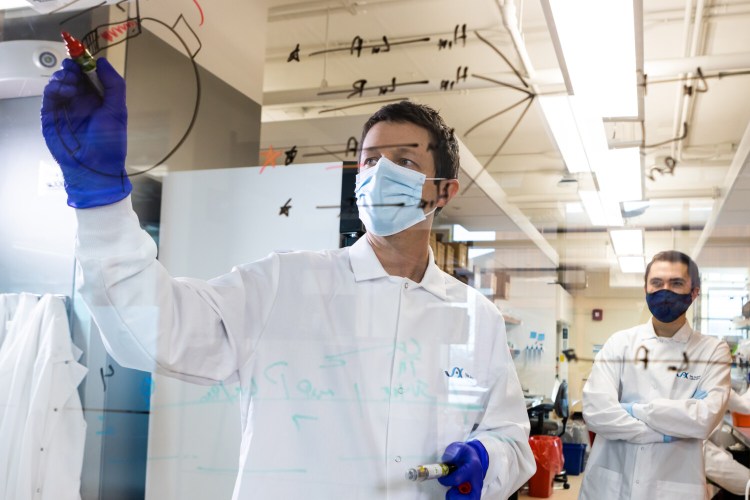

For the better part of a year, Tewhey has been leading a team of eight scientists at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor that has been conducting the bulk of variant testing on positive COVID-19 tests in Maine.

When the delta variant that is responsible for the current dispiriting surge first arrived and then became the dominant strain almost overnight, he was among the first to know. And he’ll likely be first if or when the next variant emerges as well.

“The virus is always evolving. That’s a natural part of evolution, acquiring mutations,” Tewhey, 38, said in a recent interview. “And it’s important to understand what those mutations are. The majority are not going to have any sort of impact, but as we’ve seen with the alpha variant and now the delta, they do change how the virus behaves. So, what we’re doing allows us to catch changes early on and understand evolution.”

Instead of doing research, and waiting, and refining methods and doing more research, and waiting some more, Tewhey and his team are conducting what’s known as genomic sequencing on big batches of coronavirus tests every week. Their data and analysis are then shared with the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention and federal officials as well.

Maine CDC’s director, Dr. Nirav Shah, said Maine has consistently been sequencing a higher percentage of positive tests than nearly every other state. That wouldn’t be possible without the work of Tewhey and his colleagues, whom he called “the real deal.”

“But for the partnership with Jackson Lab, I shudder to think where we’d be,” Shah last week. “We’d be outsourcing this to another state or private lab.”

It’s not what Tewhey, a Gorham native and University of Maine graduate, thought he’d be doing when he returned to Maine four years ago to set up his research team at the world-renowned Jackson Lab. He was supposed to be studying genetic mutations associated with complex disorders, such as Type 2 diabetes, over a long period of time. But the pandemic upended lots of jobs.

“The first few years is always dicey when you’re trying to get your research established and projects up and running,” he said. “I think everyone in the lab recognized what’s more important, … so to be able to contribute to something that is immediately useful to the public, that’s been meaningful.”

GENETICS CLICKED

Tewhey ended up at the University of Maine like so many other of the state’s high school graduates. His mother went there. So did his grandparents and other family members. And the financial aid package was good.

He had already developed an interest in science at Gorham High School and furthered that by studying biochemistry and molecular and cell biology while in Orono.

During a year studying abroad at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, he took his first genetics class. That’s when everything clicked, he said.

“It just matched up with how my brain operates,” Tewhey said. “After that first class, I knew genetics.”

Ryan Tewhey in his research lab at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor. Tewhey leads a team of eight, including research associates Daniel Berenzy, left, and Susan Kales, right, that has been conducting genomic sequencing of positive COVID-19 tests in Maine to determine if they match any of the many identified variants, such as delta. Tiffany Laufer/The Jackson Laboratory

He returned to UMaine for his final year of college and graduated in 2005. Author Stephen King gave the commencement address and his words resonated.

“The focus of his speech was that you need to go out and see the world but then come back to Maine,” Tewhey recalled. “I always took that to heart. And I knew it was something I’d do. My family is here. My wife’s family is here.”

While debating about where he wanted to do his graduate work, he worked as a researcher at the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard in Massachusetts, a leader in human genetics.

From there, he found a doctoral program about as far away from Maine as possible without leaving the country – the University of California, San Diego. He spent five years there and came away with his Ph.D.

Tewhey returned to the Broad Institute for a short time while looking for faculty and research positions. He applied across the U.S.

“In academia, it can be tough,” he said. “You go where you’re able to go.”

He was fortunate to land a position in his home state, at one of the world’s foremost genetics labs, which employs more than 2,000 people in Maine, Connecticut, California and China and has an operating budget of $500 million.

“I jumped at the opportunity to come here,” he said. “There are very few places in the country that can provide what Jackson Lab can. It’s world class in its resources. I got really lucky.”

Tewhey lives in Southwest Harbor, the quiet side of Mount Desert Island, with his wife and twin 1-year-olds.

REACHING OUT TO MAINE CDC

Although Tewhey is a human geneticist by training, he had never worked with mice, which is what Jackson Lab is best known for.

He began in 2017 by studying how variations and mutations in people’s genetics contribute to complex disorders, such as Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune disorders.

That research was still in the early stages in the spring of 2020 when his team reached out to the Maine CDC, whose own lab, the Maine Health and Environmental Testing Laboratory, was starting to get a little busy with a novel coronavirus that would soon upend the world.

“We reached out and said, ‘We’re here. What can we do to help?” Tewhey explained.

The state’s lab has the capacity to sequence tests but not at the same scale as Tewhey’s lab in Bar Harbor. In simple terms, sequencing involves taking a sample of a positive test, amplifying it to see every minute detail and then comparing it against hundreds of others to look for differences and matches.

“Sequencing, it’s a different beast altogether than the normal diagnostic work at (the state’s lab),” Shah said. “It requires supercomputer-level processing power and really detailed analysis. All labs can do it and we have done it, but it’s not what a public health lab is set up to do, particularly to do the high volume that’s needed.”

Initially, the state sent about 100 samples early on so that Tewhey’s team could prepare for what the process might look like.

“Then we didn’t do a whole lot for a few months,” Tewhey said. “Sequencing wasn’t really on the radar then – and there was no money for it. It wasn’t until later in the fall when it started to become part of the conversation.”

By that time, the coronavirus had been spreading all over the world and doing what every virus does – mutate.

Dozens of coronavirus variants have been discovered already and some, like delta, have been elevated to variants of interest, which means epidemiologists are watching them closely.

A SURGE IN TESTS

Tewhey said his lab typically receives a shipment of test samples from the Maine CDC once a week.

“Usually, as soon as the box comes, it’s go time,” he said.

The more positive tests the state tracks, the more samples get sent to Bar Harbor. Before the delta variant took over, it was 100 tests a week or less. Now, it’s closer to 400 or 500.

“I think the biggest pressure is keeping up and maintaining a level of surveillance that’s actually useful,” Tewhey said.

For instance, Shah said he started to notice about eight weeks ago in Tewhey’s weekly report to the Maine CDC – which looks like Sanskrit to most people – that the prevalence of the delta variant was rising precipitously.

“We started seeing delta go from 1 percent of cases to 5 percent to 10 percent,” Shah said. “At that time, we were having conversations with hospitals as we always do and I said to them, ‘OK, it’s on its way here. Get ready.’”

The sequencing efforts at Tewhey’s lab have enabled health care organizations to prepare for expected surges. Within a few short weeks, the delta variant was detected in virtually all of the samples sequenced.

Tewhey said he was stunned at how rapidly the delta variant began to outpace the alpha variant, which was first detected in the United Kingdom and was the dominant strain in many areas for months, including the U.S.

“They are both highly transmissible, but when alpha arrived, it was competing with slow cars and outdriving them. Now, delta is matched up against a fast-driving car in alpha and it’s going even faster,” he said.

Tewhey doesn’t know what’s next for him and his team. The pandemic has routinely required adjustments in expectations. And he still has to meet grant deadlines on his other research.

But he’s glad to play a part.

“The past year and a half has been hard on everyone in different ways,” Tewhey said, and he and his team are no exceptions. “Watching the cases, hospitalizations and deaths increase is extremely sad, but I don’t think that has directly impacted our morale. We continue to push to get done what needs to be done.

“The difficult part for me is that all the heartache from this summer could have been largely prevented. We were incredibly fortunate that science delivered truly amazing vaccines and yet here we are. That realization is disheartening both as a scientist and as an individual who wants to see this pandemic behind us.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story