In early March, things were looking up for Justin Hafner, a 23-year-old University of Maine graduate and co-founder of a software startup based in Portland that marries kinesiology and virtual reality in order to improve athletic performance and reduce the chance of injury.

KinoTek was one of eight Maine companies that, five months earlier, had attended TechCrunch Disrupt, an international conference for tech startups in San Francisco. Startup Maine, a Portland-based nonprofit advocating for entrepreneurship, funded the trip with proceeds from ticket sales to its own annual three-day conference for Maine entrepreneurs last summer.

Thanks to contacts made at TechCrunch, Hafner lined up a return to California in mid-March. He planned to spend a week each in San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego, meeting with potential investors and touting a recent partnership with technology giant Microsoft. A handful of professional basketball, baseball and football teams were interested in KinoTek, as were four college sports programs.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic. Within 48 hours, every meeting was canceled. Hafner stayed home. By early April, even the pro teams had lost interest, having been frustrated by other biotechnology bonanzas that hadn’t panned out.

“We had so much momentum,” Hafner said. “We were going to go on a road show, not just in California but all over the United States. We didn’t know what to do.”

Three months later, KinoTek has new life thanks to an unexpected pivot away from sports, but Startup Maine has canceled its multiday educational and networking conference that had been scheduled for later this month. In an environment in which failure is commonplace even in the best of times, not all local startups have been able to survive the coronavirus disruption.

“From the stories we’re hearing, they’re all struggling,” said Tom Rainey, executive director of the Maine Center for Entrepreneurs. “This has been a really hard time.”

Rainey said he has not heard of any layoffs among the companies in his network, but there have been furloughs with the expectation of eventually returning to work. Since March 11, there have been 63,580 layoffs at 490 startups worldwide, according to online tracker Layoffs.fyi, with roughly two-thirds of those based in the United States.

KinoTek founders David Holomakoff, left, and Justin Hafner at Hafner’s Portland apartment. The software startup had a virtual reality and kinesiology focus, but they shifted from sports to digital health when the pandemic changed potential clients’ interests. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

On the bright side, Rainey said, of the 44 startups enrolled in a five-month entrepreneurial boot camp that culminates in the group’s Top Gun Showcase each spring, only two dropped out because of issues related to the pandemic when the sessions changed from in-person classes to a weekly Zoom call.

“We really did expect things to go a lot worse than they did,” Rainey said. “I think they all looked forward to having that time together.”

Rainey pushed back the pitch competition for Top Gun finalists from May to late summer or early fall. The plan is to still have live judging, but with an online audience.

Another of the center’s programs called Cultivator focuses on food, beverage and agriculture businesses, all of which had to quickly learn about online sales because many of their traditional outlets – restaurants, fairs, festivals, specialty stores – either shut down or scaled back operations. Under stay-at-home orders and with social distancing precautions, “people like to shop at fewer places,” Rainey said. “They just want to be someplace where they can pick up all their goods.”

WORK SPACES DISRUPTED

Having time together with other budding entrepreneurs to commiserate, inspire and learn from each other helps build networks of support. Many young companies found that environment in co-working spaces such as Cloudport, Think Tank, CoworkHERS and Peloton Labs, where social interaction helps nurture incubation.

Of course, the effort to halt transmission of a highly infectious virus discourages – if not outright bans – the sharing of desks, cubicles, conference tables, kitchens and bathrooms. Local co-working operations either closed altogether or allowed access only to members with dedicated offices.

Heather Ashby, who owns the female-focused CoworkHERS on Congress Street, dropped most of her members to a $10 monthly hold fee in order to cover her printing and information technology contracts. Currently, she is in the process of remodeling and rearranging furniture to allow for social distancing.

Gone are the open bowls of mixed nuts and pretzels. Only wrapped snacks now. Sneeze guards are being installed on top of desks. A basement gym has been closed, but may be repurposed as a yoga studio.

After surveying members, Ashby plans to reopen in July with online software for scheduling time and space so that if someone becomes symptomatic it would be easy to inform others of possible interactions. She said only two of her 85 members have canceled, and third-floor renovations are underway that would provide more office space.

“Most of the women are doing things like coaching, counseling or therapeutic work, so the open space didn’t work well for them anyway,” Ashby said. “Before, it was keeping everyone happy. Now, it’s keeping everyone safe.”

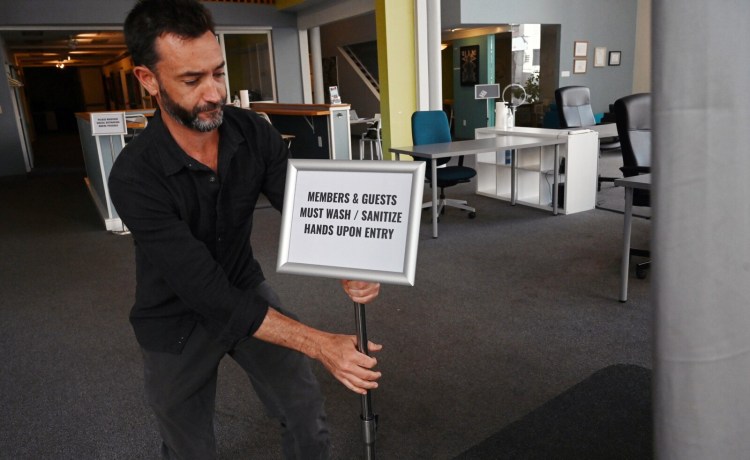

Patrick Roche of Think Tank Coworking has made changes to the location on Congress Street in Portland. Desks are now spread farther apart and high-touch amenities like magazines and snacks are gone. Cleaning supplies are on the desk at back right. Roche said membership declined about 30 percent in April and May. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Patrick Roche, whose Think Tank co-working spaces operate in Yarmouth and Biddeford as well as on Congress Street in Portland, said membership declined by about 30 percent in April and May, mostly among floating members rather than those who rent private offices. He also sees an emergent category of people being told to work from home who are finding that situation less than ideal, particularly with frequent domestic interruptions from a spouse, child or pet.

Also looming on Roche’s horizon are more companies with a remote-first culture, where employees may have space at corporate headquarters but the majority of them work remotely. Such trends may keep co-working spaces in business, but all the meet-ups, happy hours and networking events that serve as the lifeblood of the entrepreneurial ecosystem are currently sidelined by social distancing guidelines.

“We’ve been through phases where we would host five to seven events a month,” Roche said. “It was an epicenter of entrepreneurial thinking. That’s probably the biggest loss. So for the next couple months, people will be wondering, ‘Where’s my resource hub? Where do I go to get support and inspiration?'”

CONNECTIONS SEVERED

Katie Shorey, the president of Startup Maine, said any consideration of going virtual with their annual three-day conference was quickly dismissed. Meeting in person has always proved more valuable, she said, and there are plenty of webinars and virtual meet-ups already happening in Maine.

Raising capital and growing a customer base are challenges faced by all nascent companies, and the pandemic has made those even harder.

“We were in such a good place before the pandemic hit,” Shorey said of the state’s entrepreneurial environment. “The job market was great, and I just hope that can bounce back. But startups are so used to operating, I don’t want to say at a minimum, but they’re just gritty.”

Rosa Noreen owns the Bright Star World Dance Studio and has been teaching ballet and belly dancing for nearly 15 years, but only for the past two or three has it been her main source of income. She rents out studio space to other instructors and also does some bookkeeping, which is why she joined CoworkHERS, and had a monthly gig at the L.L. Bean store in Freeport doing product demonstrations for a retailer based in Virginia.

She said being creative both in what she does and how she operates in the business world has made her more nimble in the face of adversity.

“We’re used to the stress of ‘Where is my next big chunk of money coming from?’ ” she said. “We’re used to thinking on our feet, used to doing things that people aren’t already doing. So I think we definitely have a skill set that sets us up for success in the face of unusual circumstances.”

With help from her partner, Samuel James, who is a musician, along with another friend knowledgeable about sound engineering and microphones, Noreen has been able to set up a system at home that allows her to teach classes and monitor students in real time well enough to make adjustments and provide feedback. She brought home a large television set from her studio and connected it as a second monitor in gallery mode.

Roche of Think Tank Coworking prepares signs on his laptop to encourage social distancing at work. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

“Zoom is not made for teaching dance,” Noreen said. “It has a high frame rate, but you have to kind of hack it to make the music and voice aspect of it work.”

Noreen’s various businesses didn’t qualify for the federal Paycheck Protection Program or an Economic Injury Disaster Loan, so like many solo entrepreneurs, she’s been forced to navigate through these uncertain times on her own. She said she wishes there would be more governmental assistance, because she believes many small businesses may not be able to weather this storm.

Although she is working more and making less money, Noreen said she is grateful for the students who have stuck with her. Doubtful at first about teaching remotely, she now feels her mood uplifted by the experience.

“It doesn’t change the world,” she said, “but it makes me better able to deal with it.”

Devin Green, another CoworkHERS member, is a certified life coach and small-business consultant. In the midst of the pandemic, she decided to launch a new platform that potentially could become a business.

The Connected Way is something she said has been gestating for two years. Currently, she said it’s just emails and accounts on Facebook and Instagram about connecting dots and finding different ways to support people.

The week that most business activity shut down in March, Green found herself sewing nearly 400 masks for friends and colleagues.

“That took over my life a little bit, but it made me feel connected to other people,” she said. “It’s a way of living, of being, of prioritizing. It’s my path, and I believe it’s the path that makes sense with all this transition we’re going through.”

MOVEMENT RESTRICTED

HighByte is another Maine tech startup that joined KinoTek at the October conference in San Francisco. A software company focused on data integration and security in industrial environments, HighByte had just secured $875,000 in funding from angel investors and early-stage venture capital firms as well as a long-term, low-interest loan from the Maine Technology Institute.

Incubated at Cloudport, the HighByte team has no problem with working remotely. Some already had been working from home. Not being able to travel was more of a challenge, as was the fact that so many industrial plants where the software could be deployed had become off-limits to outside contractors because of pandemic restrictions.

“We work with a lot of people who go in and do installation and integration,” said Torey Penrod-Cambra, HighByte co-founder and chief marketing officer. “So there was a lot of slowdown in sales and the ability to install software.”

Jeff Peterson of Portland, a pediatrician pursuing a master’s degree in creative writing, works Thursday at Think Tank Coworking. Founder Patrick Roche said the pandemic has robbed startups of networking events and happy hours. “We’ve been through phases where we would host five to seven events a month,” he said. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

She said having cash on hand allows her company more freedom in making choices through a rough short-term patch. Instead of targeting automotive industries, her team can reconfigure marketing plans and maybe pivot toward consumer packaged goods.

Another bonus is that, with so much work being done remotely this spring, the pool of potential employees suddenly seems deeper. HighByte has fielded resumes from all over the country as well as Canada. Post-pandemic, major cities may no longer be such concentrated centers of talent.

Even within Maine, the digital transformation may help create a more inclusive playing field by bringing in organizations for which a trip to southern Maine might take hours. One of the great aspects of the TechCrunch trip for Penrod-Cambra wasn’t so much meeting potential West Coast investors but becoming more friendly with her fellow Maine entrepreneurs.

“Most of us didn’t know each other before we left,” she said. “It’s ironic that we all had to go to California to meet each other, but it was a really powerful experience that way. We built a lot of business relationships and friendships among the founders and now we pass along talent, we share notes on investors, we ask about hiring best practices and we talk to each other about the impact of COVID-19 on our businesses.”

As for KinoTek, the pandemic thrust telehealth services to the forefront. That, coupled with market research gleaned from the national Techstars Sports Accelerator program in which KinoTek fell just short of advancing to the final 10, convinced founders Hafner and David Holomakoff to change focus from sports teams to digital health.

Hafner said physical therapists, who traditionally need an hourlong, in-person session to properly diagnose an ailing patient, could now get what they need remotely in five minutes using his company’s technology. Also, because the patient can see and better understand the underlying issue, there’s more bio-awareness and more buy-in.

“It’s kind of crazy, but COVID actually helped us out a lot,” Hafner said. “We were able to figure out things and make changes to our strategy. We even hired two new employees during this (bringing the total to six full-timers) and we never expected that.”

A national digital health organization invited Hafner to take part in an upcoming panel discussion about artificial intelligence and emerging technology. Private equity firms and venture capitalists are making inquiries.

“The past two weeks, it’s been hard to keep up with everything going on,” he said. “It’s been like a roller coaster. We went from ‘the world’s falling apart’ to finding a spot in digital health, and now we’re on the upswing.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story