These days there are just three of us at home — we are always at home — and one of us (the cat) doesn’t talk.

I say this to explain why, perhaps, I have become interested in the many handwritten notes in my cookbooks; the technical term is marginalia, or, according to Don Lindgren, who sells rare cookbooks at Rabelais in Biddeford, “evidence of use.”

Since, like most of us these days, we inevitably eat three meals a day at home, I am cooking a lot, so also paging through my cookbooks a lot. If I tire of talking to Joe or the cat, if I need escape from the high, incessant anxiety of pandemic 2020 America, my scribbles let me travel in time and space, visiting with past selves and conjuring past apartments, cities, jobs and friends.

This is a small stack of the cookbooks that Grodinsky has littered with sticky notes and scribbles in the margins. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Through my notes, I have recently trekked to the Florida Everglades, sharing with my sister Carolyn some Sesame Seed Cookies from “Something Warm from the Oven”; time-traveled to New Year’s Eve 2018, celebrating with Joe over Seared Scallops and Noodles with Salted Black Bean Sauce from “Cooking One on One”; dropped by my old office in Houston, Texas, where the Almond Lemon Tea Cake from “Tartine” earned an excellent reception, though personally I found it a tad “too rich”; and connected with an old friend from my New York City days, a fellow I haven’t thought of in years, I’m having trouble even remembering his name, but I easily remember how much it thrilled me to cook a multi-course Indian meal together in his kitchen, centered on Marinated Shrimp with Whole Spices from “An Invitation to Indian Cooking.”

Attorney Beth Valentine, who lives in Gorham and owns “45ish” cookbooks, understands. “When I go back to my cookbooks and find notes,” she said, “it’s a conversation I’m having with myself over the course of years.”

The notations on that last shrimp recipe, by the way, belong to the friend I’ve lost touch with, and they are nothing like my own notes. Where I write annotations like, “A nice cross between something a little old Italian mom might make you for breakfast and (something) you’d eat at a first-rate greasy diner” (on a recipe for Fried Eggs with Italian Frying Peppers from “The Good Egg”), he has neatly underlined four ingredients in blue ink: the shrimp, black pepper, olive oil and turmeric. A ruler was involved I am sure, and probably a fine point, felt-tipped pen; I always use ballpoint, so the ink won’t run when, say, a blob of overnight waffle batter lands on the page (splatternalia, a whole other field of study, it turns out, and my new favorite word). I scrutinize the instructions for the shrimp dish and am able to puzzle out what my friend was doing: each of those ingredients marks a turn, a spot where the recipe breaks into a new step. It’s an engineer’s approach to marginalia, although if memory serves, he was a banker.

TAXONOMY

Setting aside for a moment whether the notes in your cookbooks are your own, or perhaps your mother’s or grandmother’s, it’s clear from a casual survey of my own cookbooks and consultations with other Maine cook-scribblers that recipe marginalia is easily classified by type:

• Additions and deletions, which serve to make the recipe your own

• Ratings, including reactions from eaters – often a spouse – and reconsiderations. The first time I made those sesame seed cookies, I found them “birdseedy.” The second time, granted I was camping so hungrier, I jotted down “Mmm!” and noted, by name, the enthusiastic endorsement of three other cookie eaters.

• Admonitions, like this one Chebeague Island resident and retired Episcopal priest Mary Cushman has written to herself, “in big letters” on a favorite recipe for fish chowder: “This gets saltier if it sits.” “Every time I have to read that note,” Cushman said, “because I am a salter. Every time I read the note and say, ‘Mary, do not put too much salt into this recipe.'” James Schwartz, an avid home cook who lives with his husband Tim in Cape Elizabeth, characterizes a similar note on Page 164 of his copy of Jacques Pepin’s “Fast Food My Way” as a “cautionary tale.” “The pages are totally splattered and the notation at the top says, ‘Tim nearly killed us. 12/2/2010.’ Then midway through, where it says ‘add vinegar to the drippings,’ I’ve noted in large letters: ‘Remove pan from heat and watch out for splatters!’ ”

• Corrections and clarifications

• Conversions, say from pounds to cups or ounces to grams

• Descriptions, plainly my bent. Next to the recipe for Lost and Found Honey Cake in “Heirloom Baking with the Brass Sisters,” for instance, I’ve written this: “A maiden aunt sort of cake. Pleasant in a spinster tea kind of way.”

• Records of time, place and companionship. Several years ago, South Portland freelance writer Jersey Griggs marked up her copy of “The Silver Palate” on the recipe for Beef Stew with Cumin, a dish she says lasted for days when she made it during a storm that did the same: “1/27/2015. Storm Juno – Blizzard of 2015.” As with most systems of classification, these categories are not inviolable. Griggs’ storm/stew note continues, bleeding into both additions and ratings: “Added 1 chopped onion, 2 carrots, 3 potatoes. Delicious again!”

• Reassurance, as in “might be runny. Don’t fret, it’ll bake fine and taste super,” my note on Step 6 of the Cherry-Cream Cheese Bread in “Something Warm from the Oven”; my copy of this book, you may have sussed out, is heavily inked.

• Cross-referencing. “The other thing that I do in the notes in my cookbook is to tell myself to go to another cookbook,” Cushman said. “Do you know who Maida Heatter is? It was a dark day when she died.” Cushman will be paging through a cookbook in her collection, searching for a recipe for lemon cake, say. She’ll get to the right page, only to find her handwritten note from a past baking venture: “‘Don’t make this. Make Maida’s.'”

• Equipment, noting, perhaps, the eccentricities of a particular oven or which size grater to use from your vintage yard sale collection. In my own notes, Michael’s grandmother’s bundt pan shows up a lot. Michael is German, and my former brother-in-law. When his grandmother died, he carried her battered bundt pan across the ocean and gave it to me; I treasure it. It’s not nonstick, though, or the standard American size, so it requires diligent greasing, as well as careful calculations of batter amounts. Notes to that effect appear beside many recipes in my baking books. My sister and Michael divorced more than a decade ago; he has since moved to Japan. But in the notes in my cookbook, he is in some way still a part of our family, an ongoing presence.

Because we dip into them again and again, cookbooks reveal “some of the most complex evidence of use,” Lindgren said. “When you make a dish, you’re converting the words into an action. Then we want to formulate our thoughts about what we just read. There’s a back and forth. This is a process, not just a static recognition of what we ate today. This is going to continue into the future.”

It’s a neat trick – my marginalia, a 25-cent word for what are really just untidy scrawls, remind me that these dark days will pass. This virus will not halt our lives and livelihoods forever. With face masks, six feet of space, and luck, I will be cooking, eating, responding and scribbling tomorrow, next week and next year.

TRACKS IN THE DUST

Griggs said she picked up the habit of making notations in cookbooks from her mother. Recently, though, she noticed her mother now Xeroxes the recipes she is trying out and makes notes on the copies instead. “I completely disagree,” Griggs said. “I consider it a badge of honor when I have a splattered cookbook, and the spine is falling apart. It shows it is well loved, and it means there are many good recipes in that book. I don’t think they should be kept pristine.”

That’s a judgment it took Schwartz, a former restaurant critic for the Press Herald, a little time to reach. Writing in books was a no-no when he was a child, with the exception of exercise books like grammar books, a fact that accounts, in small part, for the tentative notes he used to make in his cookbooks. Plus, he was a novice in the kitchen.

“I thought cookbooks were sacrosanct and recipes were not merely guides but they were actually road maps,” Schwartz said. “As I got to be a more confident cook, I started to realize I could write down on the pages with the recipes either simple responses or improvements that worked for my palate. My original remarks said things like ‘great’ or ‘excellent’ or ‘meh.’ They were all in pencil. I still had deep respect for the book. Now I’ve moved to pen and I scrawl.”

Cooks have been writing notes in cookbooks for centuries, according to Lindgren. In Cushman’s case, it has been more than 50 years. One of her older notes is on a custard sauce recipe to serve with snow pudding in her 1975 “Joy of Cooking”; in fact, the recipe is “so buried in notes it is almost indecipherable.” Her paternal grandmother taught her to make the pudding when she was 13, instructing her to stir the sauce with a silver spoon. “I am 77. I have a note in my cookbook that says, ‘Silver spoon!’ It’s a very old note, but I have never made custard sauce without a silver spoon,” Cushman said.

“In a crazy way, the notes are a road map to other relationships,” she continued. “I never make custard sauce without thinking about my grandmother. The notes are tracks in the dust.”

Personal history: priceless. Hard cash value? It depends. Booksellers who deal in newer cookbooks usually want a clean copy, Lindgren said. But wait long enough, and marginalia may add value or at least saleability, as it can convey useful and often gripping information about a rare book’s history, and by extension ours. “It’s an entirely new narrative, on top of or in addition to the narrative that the author has given us,” Lindgren said.

UNFOLDING

A few weeks ago, in the middle of my work day, I baked Not-Just-For-Thanksgiving Cranberry Shortbread Cake from my the much-annotated copy of Dorie Greenspan’s “Baking from My Home to Yours” in order to 1) use up a bag of cranberries that I’d bought last fall and frozen and 2) provide a photograph for this story. As I sprinted between my keyboard and my kitchen, I ignored Greenspan’s instruction to cook the cranberries for 5 minutes “stirring almost constantly.” Work pressed. I had no time for constant stirring.

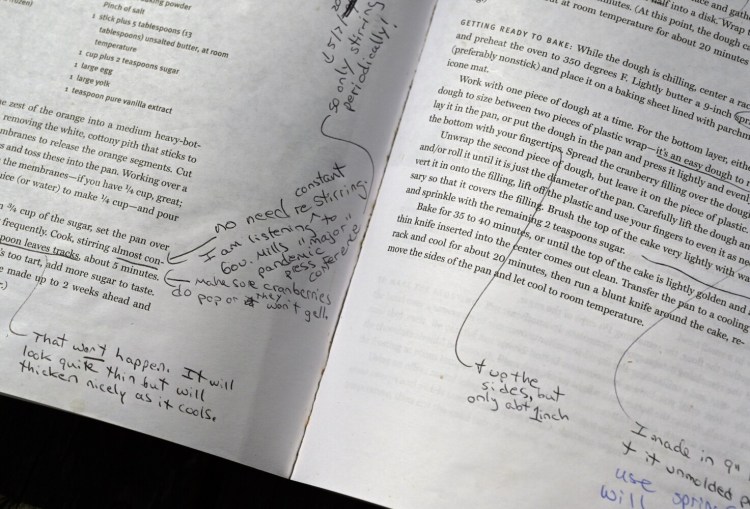

When the cake was done, sliced and tasted, I set the cookbook on my table, picked up a pen and added a new note to the considerable scribblings that already hemmed in the page: “No need re constant stirring. I am listening to Gov. Mills ‘major’ pandemic press conference on computer, so only stirring periodically. 5/7/2020.” Despite my failure to follow orders, however, the cake came out exactly as it always does: “Yes! Lovely! Impressive in a homey way,” as I’d rated it in notes in the margins in a different colored ink years before.

——-

FRIED EGGS WITH ITALIAN FRYING PEPPERS

Recipe from Marie Simmons’ “The Good Egg.” These make excellent lockdown cooking, as they require few ingredients and most of them you’ve probably already got.

Makes 2 servings

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 garlic clove, bruised with the side of a knife

1 pound Italian frying peppers, halved, cored and seeded

1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

4 large eggs

Italian bread, toasted if desired

Heat 2 tablespoons of the oil in a large nonstick skillet over medium-low heat. Add the garlic and cook until lightly browned, 2-3 minutes. Remove from the oil and discard. Add the peppers, cover and cook until softened, about 10 minutes. Uncover and cook, stirring, until the peppers are browned in a few places, about 5 minutes. Sprinkle with the vinegar and stir to coat. Add salt to taste and a grinding of pepper, transfer to a medium bowl and cover to keep warm.

Add the remaining 2 tablespoons oil to the skillet and heat until hot. Break the eggs one at a time into a cup and slip into the skillet. Reduce the heat to low and fry until the whites begin to set, about 1 minute. Cover and cook until the yolks are cooked to the desired doneness, about 5 minutes more. Transfer the eggs to two plates, place the peppers on the side and pour any juices from the peppers over the eggs. Serve at once with the bread.

NOT-JUST-FOR-THANKSGIVING CRANBERRY SHORTBREAD CAKE

Adapted from Dorie Greenspan’s “Baking: From my home to yours,” with my many notes incorporated.

Makes 8-10 servings

For the jam filling:

1 large navel orange

1 (12-ounce) bag cranberries, fresh or frozen (not thawed, if frozen)

1 cup sugar

Dash salt

For the cake:

2 1/4 cups all-purpose flour

1/4 cup wheat germ

1 teaspoon baking powder

1/4 teaspoon salt

13 tablespoons unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup granulated sugar

1 large egg

1 large yolk

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

2 teaspoons turbinado sugar

To make the filling, grate the zest of the orange into a medium heavy-bottomed saucepan. Slice off the peel with a very sharp knife, removing the white cottony pith that sticks to the fruit, and slice in between the membranes to release the orange segments. Cut these segments into 1/4-inch pieces and toss into the pan. Working over a measuring cup, squeeze the juice from the membranes – if you have 1/4 cup, great; if not add enough additional orange juice (or water) to make 1/4 cup and pour into the pan.

Put the cranberries in the pan, stir in 3/4 cup of the sugar, set the pan over medium heat and bring to the boil, stirring occasionally. Cook, until the cranberries pop (important, or the sauce may not gel), about 5 minutes. The sauce will thicken as it cools. Scrape the jam into a bowl and taste it – if it’s too tart, add more sugar to taste. Cool to room temperature. (The filling can be made up to 2 weeks ahead and stored in the refrigerator.)

To make the cake, whisk together the flour, wheat germ, baking powder and salt.

Working with a stand mixer, preferably fitted with a paddle attachment, or with a hand mixer and a large bowl, beat the butter on medium speed until soft and smooth. Add the granulated sugar and continue to beat until it dissolves into the butter. Reduce the mixer speed to low and add the egg and yolk, beating until they too are absorbed. Beat in the vanilla. Add the flour mixture, mixing only until it is incorporated; since this is a delicate dough, one that should not be overbeaten, you might want to finish mixing in the flour by hand using a sturdy spatula. You’ll have a thick dough, one that is quite malleable.

Turn the dough out onto a smooth work surface and gather it together into a ball, then divide it, with one part slightly bigger than the other. Pat each piece into a disk. Wrap the disks in plastic and refrigerator for 15 to 20 minutes. (At this point, the dough can be refrigerated overnight; set it out at room temperature for about 20 minutes before proceeding.

While the dough is chilling, center a rack in the oven and preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. Lightly butter a 9-inch springform pan (preferably nonstick) and place it on a baking sheet line with parchment or a silicone mat. (I prefer a 9-inch cake pan, first greased and lined with parchment, no baking sheet required, nor is nonstick necessary in my experience.)

Working with the larger piece of dough, roll the dough to size between two pieces of plastic wrap – it’s an easy dough to roll – and lay it in the pan, or put the dough in the pan and press it lightly and evenly across the bottom with your fingertips, and about 1 inch up the sides of the pan. Spread the cooled cranberry filling over the dough.

Unwrap the smaller dough disk and roll it to just the diameter of the pan. Carefully invert onto the filling, lifting off the plastic. Brush the top of the cake lightly with water, sprinkle with turbinado sugar, and pierce all over lightly with a fork to prevent the top of the cake from hillocking.

Bake for 35 to 40 minutes, or until the top of the cake is lightly golden. Transfer the pan to a cooling rack and cool for about 20 minutes. Then run a blunt knife around the cake, remove the sides of the pan and let cool to room temperature.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story