Concerns over Maine’s fisheries are nothing new. Nearly 200 years ago, when Maine was a very new state, its citizens were also worried about the status of its fish populations.

As early as 1829, to take one instance, fishermen noticed a decline in the numbers of fish in the Penobscot River. Historian Suzanne AuClair wrote about the period in “The Origin, Formation & History of Maine’s Inland Fisheries Division.” Fishermen were so alarmed, she wrote, that “a law was enacted that required Penobscot, Waldo, and Hancock counties to appoint three fish wardens to examine all dams after the 10th of May each year to ensure fish passage was available.”

These early efforts to ensure that sea-run fish could reach their spawning grounds failed utterly. Over the next 150 years, dams would prove a severe threat to many of Maine’s sea-run fish populations.

Today, a number of those dams have been removed. Maine is home to the most wild brook trout waters in the Lower 48, as well as the only wild Arctic char populations. The last wild Atlantic salmon population in the country are in Maine. Still, the state’s waters are far from truly pristine.

As Joseph Zydlewski, a professor of fisheries at the University of Maine, put it, people have had some impact “just about everywhere” in Maine. “If you can reach it, people have tried to manipulate it.”

Scientists today point to four apocalyptic conditions that at various times have devastated Maine’s fisheries: The widespread construction of dams; pollution; overfishing; and the introductions, both legal and illegal, of non-native fish. Many now add a fifth to this list of threats: climate change.

On the eve of the state’s traditional opening day for the open-water season — April 1 — and as the state’s bicentennial anniversary month draws to a close, we take a brief look back at the history of Maine’s fisheries, highlighting one species that has persevered, one that is struggling to survive, and a third — a non-native — that is thriving.

The Rebounder: Brook Trout

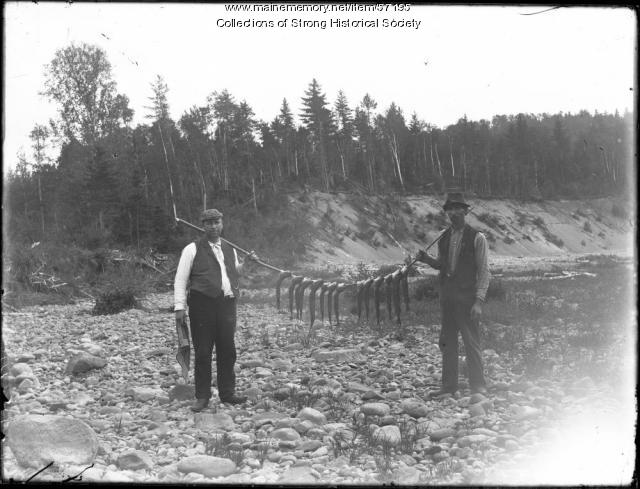

Wild brook trout in Maine were bountiful when Europeans settlers arrived in Maine, but by the late 19th century, fishermen and sporting camp owners were worried about their decline.

Overfishing was to blame: huge numbers of brook trout were sold commercially, shipped in barrels to Boston, Connecticut and New York to be sold at markets. By 1879, their numbers had dropped so precipitously, selling trout, landlocked salmon, lake trout, white perch or black bass was outlawed, AuClair wrote.

Sportsmen from around the Northeast prized the colorful brook trout so highly, they also contributed to its decline. Fish laws existed in the 19th century, but they were tough to enforce, AuClair wrote. However, in 1881, to ensure that fishermen adhered to the fish laws, the state hired as many as 60 fish wardens, and soon after, it established game warden positions.

Brook trout caught on a bamboo fly rod during a hunting and fishing expedition at Ragged and Moosehead lakes in 1895. Courtesy of Maine Memory Network

These enforcement efforts helped turn things around for the fish. Over the decades, conservation efforts by the state and environmental groups have further protected the state’s “heritage fish,” as the Maine Legislature has dubbed it. Today brook trout thrive in Maine, which is home to 97 percent of the wild brook trout waters in the Eastern United States, according to Trout Unlimited. More than 1,200 lakes and ponds are managed for brook trout; about 60 percent of those populations are sustained by natural reproduction; and brook trout can be found in roughly 22,000 miles of streams in Maine, too, according to the state.

The Disappearing: Atlantic salmon

Sea-run fish haven’t had it easy in Maine. For a good 150 years, impoundments created by dams choked off spawning habitat. Later, textile and paper mills dumped chemicals and sewage into Maine’s rivers, compounding the disaster for the fish.

The demolition of dams in the last three decades has allowed many sea-run fish species — alewife, American shad, striped bass, American eel and Atlantic sturgeon — to return to their traditional spawning grounds, and their populations are beginning to rebound.

But not all species have fared as well. Atlantic salmon, for one, have not returned in high numbers. The Gulf of Maine population has been listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act since 2000. Both the loss of spawning habitat and warming waters (caused by climate change) are in part to blame, say biologists, who continue to research other possible reasons for the fish’s decline in Maine.

The Atlantic salmon is “just barely hanging on,” said Stephen Coghlan, associate professor of freshwater fisheries ecology at the University of Maine. “And it would be gone without hatchery and stocking efforts.”

The Out-of-Stater: Smallmouth bass

While cold-water fish are struggling, the number of warm water non-native fish populations in Maine has exploded over time. The list of introduced species — the northern pike, the massive muskellunge, many more — is long. But smallmouth bass may be the most prolific non-native fish species in Maine — or at least the one with the longest history here.

“It was first introduced by the state around 1860,” Coghlan said, “and has since spread throughout almost the entire state.”

Illegal introductions of nonnative smallmouth bass were rampant at the end of the 20th century. A century earlier, as early as 1868, such introductions were legal, though, undertaken by the Maine Commissioners of Fisheries itself. Fifty-one waters in southern and central Maine received “authorized” introductions of bass between 1868 and 1881, former state fisheries biologist Kendall Warner wrote in a 2005 article for Fisheries magazine.

Two fishermen from Lyman pose with their catch after a bass tournament in 2019. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Today, Maine is home to at least 300 bass fishing tournaments and some 50 bass fishing clubs. So it’s no surprise that few fishermen complain about these non-native fish, or that state biologists manage the fisheries to ensure robust bass populations.

In his research on the history of the smallmouth bass, Warner quoted an ardent angler from 140 years ago who, it turned out, had great foresight: “That (the bass) will eventually become the leading game fish of America is my oft-expressed opinion and firm belief. This result, I think, is inevitable.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story