Second of six parts

PHIPPSBURG — Had things gone differently, generations of schoolchildren would have learned that New England began here, and one of the boulders off windswept Sabino Head might have taken the place of Plymouth Rock in the mythology of American origins.

For it was on this shore, on Aug. 19, 1607, that Sir Ferdinando Gorges and fellow investors tried to establish the Popham Colony, the first English settlement in this part of the world. A ship carrying 124 settlers and a captive Wabanaki guide arrived at this site near Popham Beach, built a fortified English village of a dozen buildings and the first English vessel ever built in the Americas, the 50-foot pinnace Virginia.

In spring, however, they boarded the Virginia and a supply ship and fled home to England having made two important discoveries: Maine winters can be very cold, and it is much more difficult to survive one if the natives have reason to despise you.

Maine is celebrating its bicentennial, but its real beginnings lay more than two centuries earlier, when rival English colonial projects began their incursions into the Wabanaki homeland, placing them in conflict not only with the tribes and French colonial ambitions but with one another. The profound differences between early 17th–century Maine and Massachusetts shaped our history to a degree rarely understood and with implications that continue to the present day.

Most Mainers are aware that Maine was once part of Massachusetts. Far fewer realize that colonization came to Maine first, and that it was an independent colony for decades prior to a hostile conquest by its southern neighbor. It was a takeover made possible by the poor decisions made by English Maine’s “founding fathers” in relation to the climate, resources and indigenous people they encountered here more than four centuries ago.

BURNING BRIDGES

Local Wabanaki were well aware that English explorers had kidnapped five of their own two years earlier, handing them over to Gorges and his fellow investor, Sir John Popham. They knew this firsthand because one of the captives, Nahanada, had escaped back to his people the previous summer while serving as an unwilling guide for an abortive colonization expedition. Another captive, Skidwarres, had been sent to guide the Popham colonists. In the first contact with the Wabanaki, he found himself face to face with Nahanada, the leader of a local band, who helped him escape under the cover of his warrior’s bow and arrow.

The Popham colonists’ project depended on trading with the Wabanaki for furs and other valuables. Instead, they found the indigenous people wanted little to do with them. The colony’s leader, Popham’s nephew George Popham, had some success restoring trust until he died in midwinter and was succeeded by the hotheaded Raleigh Gilbert, who, the Penobscots later told Champlain, “beat, maltreated, and misused (the Wabanki) without restraint.” The Kennebecs decided “to kill the whelp ere its teeth and claws become stronger.”

Plan of the Popham Colony (St. Georges Fort), settled in what is now Phippsburg in 1607. Photo from the collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of www.MaineMemory.net, item #7542

According to one period account, there was some sort of fight inside the colonists’ fort, resulting in an explosion that killed several Kennebecs. The oral tradition of the Wabanaki in 18th–century Norridgewock held that the English had asked visiting Indians to help pull a cannon into place, then fired it through them once they formed a straight line. Whatever happened, the colonization attempt had failed miserably. “All of our former hopes,” Gorges later wrote, “were frozen to death.”

COLONY: MAINE’S PATH TO STATEHOOD

Sunday, Feb. 16 – Chapter I: Dawnland

Sunday, Feb. 23 – Chapter II: Rivalry

Sunday, March 1 – Chapter III: Conquest

Sunday, March 8 – Chapter IV: Insurrection

Sunday, March 15 – Chapter V: Liberation

Sunday, March 22 – Chapter VI: Legacy

MEDIEVAL DREAMS

Gorges – who would later give Maine its name – had a vision for New England, however, one he refused to give up on.

In the early 1600s, England stood on the threshold between the Middle Ages – with its guilds and tithes, serfs and vassals – and the Early Modern world of commerce and banking, merchants and machines, innovation and upward mobility. Gorges stood solidly on the side of the old ways and wanted to recreate the neo-feudal society of his native West Country, complete with aristocratic manors, compliant peasants and loyalty to the king and the Church of England. But how to establish such a society on an unfamiliar continent?

Capt. John Smith, he of Pocahontas fame, gave him an answer: fish.

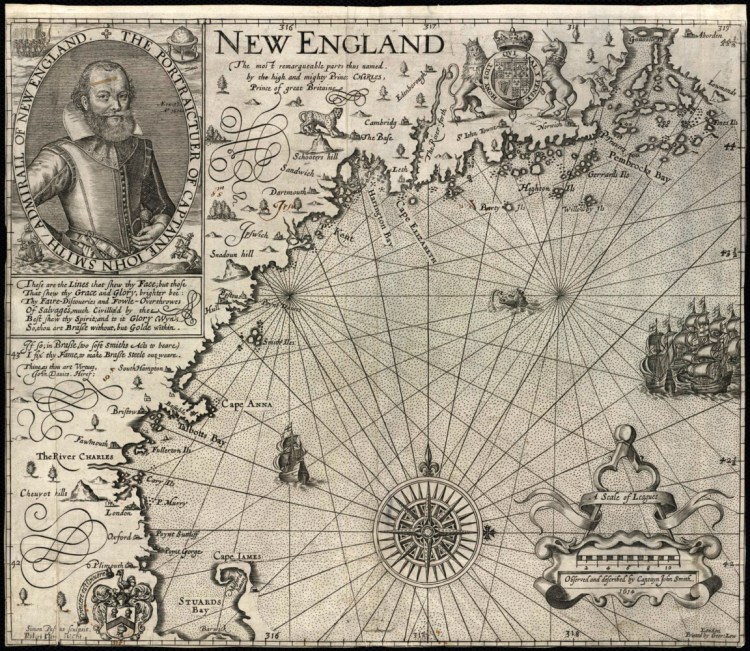

In 1614, Smith led an expedition to the Gulf of Maine, where he intended to hunt whales and mine gold from a rude base on Monhegan. Instead, he discovered the incredible bounty of the Gulf of Maine, particularly in the form of huge shoals of codfish, which could be split, cured and shipped back to ready markets in Europe. “Of all the foure parts of the world that I have seene not inhabited,” Smith wrote. “… I would rather live here than any where.” He named it New England.

The Gorges family coat of arms, which decorates the tomb of Sir Edmund Gorges, who died in 1512, and his wife, Lady Anne Howard, in All Saints Church, Wraxall, England. Photo from Wikipedia

On his return to England, Smith called on Gorges, now the leading figure in the entity that held the royal charter to the region. Gorges named him “admiral of New England” and dispatched him with two ships and 17 colonists to establish a permanent base on Monhegan. But his ship was dismasted in a violent storm and, on a second try, captured by French pirates. A third try involving three ships failed when adverse winds prevented the expedition from leaving port for months.

But other fishermen had been inspired by Smith’s accounts and at some point in the late 1610s established New England’s first permanent European settlements: year-round fishing stations on Monhegan, Damariscove, Pemaquid and Southport where men caught, processed and loaded cod. Soon Gorges’ hirelings were working the sites as his deputies collected rents from the other fishermen. Thus European Maine began in the pursuit of fish.

In 1618 and 1619, Gorges’ fishing agents reported that the indigenous people of New England had been wiped out by a terrible plague. European explorers, colonists and fishing crews had unknowingly transported Old World pathogens to the New World, and smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, measles and the bubonic plague spread rapidly among people who had no resistance to them. One traveler, Thomas Dermer, found Wabanaki lands “not long since populous, now utterly void,” the few survivors covered in plague sores.

The “Great Dying,” as the Wampanoag called it, killed 90 percent of New England’s Native Americans in just four years, leaving a post-apocalyptic landscape of abandoned villages, corpse-filled camps and overgrown fields. Before this, Gorges would have had little hope of realizing his vision, the Wabanaki and their neighbors being numerous and capable enough to repel incursions like the Popham Colony. But the plagues opened the door to full-scale colonization. The land, Gorges wrote, “was left a desert, without any to disturb or oppose our free and peaceable possession thereof.”

A woodcut of the Great Dying, a cataclysmic scourge brought upon the native population by epidemics – notably smallpox, measles and the typhus, spread by Europeans, from which they had no immunity. Illustration courtesy of the Museums of the Bethel Historical Society

In 1620, Gorges approached King James with an ambitious new plan to impose English rule over a domain stretching from the St. Lawrence to Delaware Bay and, theoretically, from sea to sea. The land would be divided between Gorges and 39 other nobles and aristocrats based on their relative feudal standing. These dukes would divide their duchies into counties and baronies and manors, collect tithes from their vassals, preside over courts and collect rent from tenants. Delighted, James gave Gorges control over this vast domain that he hoped would shore up the new English empire on the side of tradition.

It was Gorges who founded Maine’s first lasting settlements in the 1620s and 1630s: Kittery, Cape Porpoise, Saco, Scarborough, Falmouth, North Yarmouth, Pemaquid and, most important of all, the grand capital at York, which he would name Gorgeana after himself. New fishing stations were created at Richmond Island off Cape Elizabeth and at the mouth of the Piscataqua. He named what became his personal portion of his grant the “Province of Maine,” though exactly why has been lost to history. The people he sent there had particular characteristics, ones that would set them at odds with those who would establish Massachusetts.

Most of Maine’s early settlers came from the West Country, a rugged maritime region of England where respect for tradition, crown and the Church of England ran high. In one sample of 124 people who came to Maine between 1620 and 1650, two-thirds came from this region, with County Devon alone representing nearly half the total. A quarter came from the fishing hamlets and small ports of a single 25-mile stretch of the South Devon coast or the compact manors of the hills and fens where serfs had long since been driven from the land and made poor tenant farmers. They were overwhelmingly commoners drawn by the chance to farm on a hundred acres of rented land instead of three, or to fish the sea for a stable wage.

Sir John Popham, one of the leaders of the early English effort to colonize Maine. Painting copy of an original at Orchard Wyndham, by unknown artist. Photo courtesy of Somerset Museums Service

In Maine, they scattered themselves on the land in the West Country model in isolated tenant farms connected only by rivers and the sea. Many towns took the names of the places they’d left behind: Biddeford (in Devon), Falmouth (Cornwall), Wells (Somerset) and Kittery Point (a manor in Kingswear, Devon). York was first named for Bristol, the great West Country port. Their manor lords remained in England, collecting rents.

Gorges was not a very effective leader, however, not least because he never once visited the New World. Sitting in his study at Plymouth Fortress, he sent out lofty directives to his deputy governors – his nephews and a distant cousin – to collect taxes, expand settlements, appoint officials and build cathedrals.

Cousin Thomas Gorges, newly graduated from Oxford, arrived in Gorgeana in June 1640 expecting to find a teeming ecclesiastical capital. Instead, he was confronted with a rugged fishing village of fewer than 100 people sheltering in drafty longhouses on the remains of a Wabanaki village, where wolves devoured the livestock and swarms of mosquitoes preyed on everything.

Point Christian, the governor’s manor house, was in disrepair and furnished with “only one crock, two bedsteads and a table board.” He wrote his father that it looked “much like your barn.” The settlers were crude and sinful. “Justly has (Maine) been termed the receptacle of vicious men,” he reported, and a “garden of vice.” His uncle responded with orders to expand the city and appoint a mayor, 12 aldermen, 24 councilors and a half dozen other officials, which Thomas protested meant “every man in the plantation must assume offices.”

Map of the American coast, 1610, depicting the Gulf of Maine region. From the collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of www.MaineMemory.net, item#7540

By 1630, having blown through several fortunes, Gorges had managed to establish fewer than 700 English settlers in his vast domain. Nearly half of those were “accidental tourists” – the Pilgrims who, blown off course en route to the nascent Dutch colony on the island of Manhattan, wound up on Cape Cod and retroactively begged Gorges for a patent, even naming their settlement New Plymouth in his honor. (They survived the first winter by raiding Wampanoag grain caches and the second by begging food from the fishing station at Damariscove.)

Increasingly desperate to populate the land, Gorges issued land patents to lots of people he shouldn’t have, including a charlatan named Thomas Weston, who shipped a bunch of his London drinking buddies to what’s now Weymouth, Massachusetts, where they partied hard and, when their supplies ran out, took to stealing from the Pilgrims and Wampanoag alike to survive. Even worse, he gave a grant for the area around Massachusetts Bay to a group who turned out to be front men for a group of radical Calvinists who were opposed to everything Gorges valued: king, aristocratic prerogative and the official Church of England. The oversight would cost him everything and forever alter the trajectory of English North America.

PURITAN RIVALS

The early settlers of Massachusetts were from the opposing side of a great struggle over the political, economic and religious future of England. In a sample of 2,284 people who emigrated there between 1620 and 1650, 43 percent came from England’s seven easternmost counties, the most densely settled, urbanized and educated part of the country, with a burgeoning middle class and a long history of resistance to arbitrary power. They stood across the narrow sea from the Netherlands, the most sophisticated society in the western world at the time, whose innovations in religion, commerce, architecture and civics could be felt everywhere.

Oil painting of John Winthrop by an unidentified artist. Winthrop led the Puritan migration to New England and was the long-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Dr. and Mrs. R. Ted Steinbock

Those who came were overwhelmingly Puritans, radical Calvinists seeking to build a new Zion, a more perfect society on Earth. They believed themselves to be chosen by God to accomplish this “errand in the wilderness,” to build a “city on a hill” to serve as a beacon to depraved humanity. They built nucleated settlements on the Eastern model, with saltbox and “Cape” styles common in Kent and East Anglia, meetinghouses, town commons and taxpayer-financed schoolhouses wherein children would learn to read God’s words. They named many of them after Eastern English towns: Haverhill and Ipswich (in Suffolk), Springfield and Braintree (Essex), Lynn and Newton (Norfolk), and the south Lincolnshire port of Boston.

They were by and large comfortably middle class, family units traveling with neighbors and fellow congregants. Fearful that some among them might lord over them as aristocrats, they divided the land equitably and ensured every town was a little republic unto itself. Their congregations were independent, the better to ensure no bishops or other hierarchy grew over them. They cunningly brought their charter with them to New England, ensuring a remarkable degree of autonomy. They distrusted outsiders, be they Quakers, Anglicans, Catholics or Wabanaki, and had rigid requirements as to who could be full members of their communities.

And there were a lot of them. Within a few years of the arrival of John Winthrop’s first “Great White Fleet” there were 20,000 English Puritans living around Massachusetts Bay, meaning they outnumbered the settlers in Gorges’ “Province of Maine” by something like 40 to 1. Gorges realized his failure to do due diligence on his land grants was threatening his whole venture, though he and his family assumed they and the King would be able to correct the situation.

“If you had shown up in Maine in the early 1640s and told Thomas Gorges that Maine would become an economic hinterland controlled by Massachusetts, he would have gotten a laugh out of it,” said Salem State University historian Emerson Baker, who has studied early New England. “Maine had all the resources.”

In the summer of 1642, the English Civil War broke out, a cataclysmic conflict between the King – backed by much of the West and North – and Parliament, championed by the East and most Puritans. When the dust settled eight years later, Gorges had died, the King had lost his head and England had the first and only republic in its history, led by Oliver Cromwell, the self-styled “Puritan Moses.” Suddenly, Massachusetts had the support of London.

It was clear that Maine’s days as an independent colony were numbered.

Next Sunday: Conquest

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.