There is a general idea that talking about suicide and suicidal ideation makes the likelihood of someone attempting suicide go up. Nobody wants to accidentally “plant the seed” of the idea in someone’s head.

But most research indicates that talking about suicidal feelings is helpful, and overall actually reduces the rate of attempted suicides and improves mental health. As Mr. Rogers so very wisely said, “If it’s mentionable, it’s manageable.” According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death in the United States. So obviously we’re not managing it very well.

My cousin Erica died by suicide in 2015. (Technically she was my second cousin, but in my family we don’t make those distinctions.) All the cliches that get trotted out when someone dies young were true about Erica — she was brilliant, and funny, and loving, and passionate. She could tear up a soccer field like nobody’s business. She was well-traveled and spoke three languages. I looked forward to her visiting our house for holidays. She was the Cool Cousin. I wish, very much, that she was still here.

When suicide is in the news, I think of Erica, of course.

I myself have had intrusive suicidal thoughts at my low points — times when I’ll be minding my own business, going about my day, and my brain gives me an annoying pop-up notification saying, “Hey! you could kill yourself, you know!”

Now, don’t worry about me — I’ve received good therapy, and the thoughts were intrusive and occasional, not persistent and long-lasting. Also, I haven’t had them since I quit drinking. But it goes to show that — bad news — mental illness can affect anyone. But — good news! — it is treatable.

I read an article this week about Columbia University’s Lighthouse Project, which has the tagline “Identify Risk- Prevent Suicide” and contains a very short screening — six questions! — that anyone can ask anyone.

The six questions are:

1. Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?

2. Have you actually had any thoughts about killing yourself?

3. Have you thought about how you might do this?

4. Have you had any intention of acting on these thoughts of killing yourself?

5. Have you started to work out or worked out the details of how to kill yourself? Do you intend to carry out this plan?

6. Have you done anything, started to do anything, or prepared to do anything to end your life?

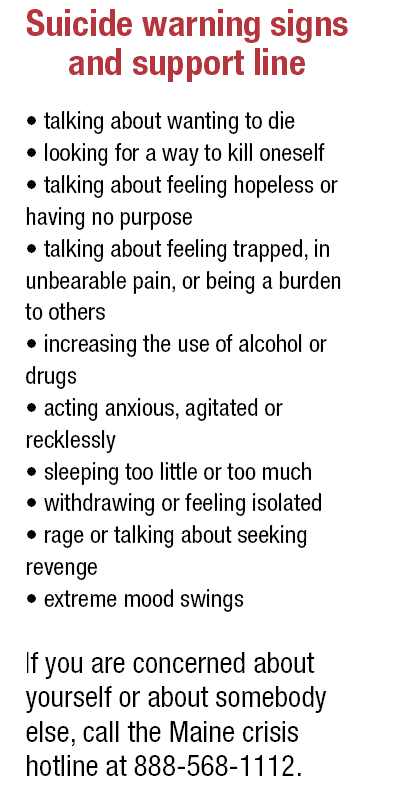

If someone answers “yes” to questions 4, 5, or 6, the Lighthouse Project says you should seek immediate care for them. If you’re in Maine, you can call Sweetser’s crisis intervention line (operated by the Opportunity Alliance) at 1-888-568-1112 and they can send a trained counselor to your house. Seriously. I’ve seen it happen; they do great work. Sweetser is a resource I wish more people knew about.

The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is also available 24/7 at 1-800-273-8255. (They also have an online chat, in case talking on the phone is a little too much to handle.) You can also talk to your primary care doctor, if you have one.

Mainers are, by our very nature, a pretty independent people, so asking for help can be hard for us, even though we all find giving help to be easy. I suspect there is also a generational gap at work here — that is, older generations may not feel as comfortable talking about mental illness as they are talking about physical illness. If that’s going to change, we’ll have to be the ones changing it.

When someone we love dies, we tend to blame ourselves a little — “Oh, if only I had driven them home that night,” “If only I had told them to get those headaches checked out.” It’s the human reaction. And when someone dies by suicide, those feelings and that guilt stay with you.

Depression, like the devil, is a liar. It digs its tenterhooks into your brain and twists your thoughts and convinces you that the world would be better off without you. But that’s a lie. The world needs you. The world wants you here. And, if you ask, the world will help.

Victoria Hugo-Vidal is a Maine millennial. She can be contacted at:

Twitter: mainemillennial

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story