Sure, now it’s old hat — the moon, yeah, been there, done that. But 50 years ago, the very thought, let alone the sight and the sound, of two human beings setting foot onto another celestial rock? Well, that took almost more imagination and more guts and more science than we could get our heads around. From five decades away, it looks like it was all neatly foreordained, but with the politics, the money, the personalities and the engineering, the moon landing was so far from being a sure thing as to make it all seem improbably quixotic.

The story of how it astonishingly came together is one Douglas Brinkley tells in his new book, “American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race.” “Moonshot” — kind of like “long shot.”

Q: One of the biggest takeaways from this book, as we look back at the 50 years since the moon landing, is that it was not inevitable; it was not destined to be. There were many things that could have made this not happen.

A: I got to interview Neil Armstrong and do his official oral history for NASA. Armstrong said they had about a 50/50 chance of having a successful mission.

President Nixon, back 50 years ago, was a little worried about having his fingerprints on Apollo 11, because if something went wrong, if we had dead astronauts in space, he didn’t want to get blamed for it.

But as soon as our astronauts were brought back alive, President Nixon embraced Apollo 11 as the heart and soul of his first year in office. So in victory, everybody kind of joined in the chorus for Apollo 11.

But the risk of it was just unbelievably high.

Q: The origins of this landing had to do with some of the technology of World War II, the idea of rocketry, of offensive weapons that were born in Germany and brought to this country by Wernher von Braun, who was one of the spoils of war, one of the rocket scientists of Nazi Germany.

A: That’s exactly right. The United States was woefully behind Germany in missile technology, and the United States government was desperate to get hold of Wernher von Braun and his technology.

And one of the great heists in world history is something called Operation Paperclip. The U.S. Army brought into America, after World War II, 137 of the top German rocket engineers — top among them Wernher von Braun.

They became Cold War rocketeers on the American side. And it’s Von Braun, a former SS officer for Adolf Hitler, who creates the Saturn 5 rocket that brought Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the moon.

Q: How did the idea of missiles and missile technology flip from offensive military weapons to instruments of exploration, of space?

A: There was always an inbred tension between the two. But President Eisenhower in the 1950s was very clear that he wanted to keep space away from being militarized. And so when we geared up with the Gemini and Apollo programs of the 1960s, it was all about peace.

It was in an era when the Vietnam War was going on. But when it came to space exploration, we were going to land on the moon not in terms of conquest but of science and lunar exploration.

Q: In Dwight Eisenhower, you had the supreme Allied commander in Europe and president of the United States. In John F. Kennedy, you had a young ensign out in the Pacific who became president of the United States. How did their differing points of view about the state of the world after the war change the nature of what was then an incipient space program?

A: President Eisenhower, having been the supreme Allied commander, had to, during World War II, sign an awful lot of death certificates, and he was focused on Europe during the war.

He knew what Adolf Hitler had done. He knew firsthand about the Holocaust and the concentration camps. To build Hitler’s rockets, that Von Braun did, they used Jewish slave camp labor. And so Eisenhower never cottoned to the idea of greenlighting Wernher von Braun’s big projects.

John F. Kennedy never stigmatized Von Braun in any way, because he thought Von Braun was just a German working for Germany, as Kennedy was an American working for America. That’s what you did during war.

So when John F. Kennedy is president, and he’s looking to do something large in space exploration, Von Braun is saying, ‘I can get us to the moon.’

He was a very fine engineer, and Kennedy like the cut of his jib and his can-do attitude.

Part of the story of my book is how Kennedy relies on Von Braun, and the belief that he could eventually build a moon rocket, to inspire Kennedy to become the president of the Space Age.

Today, when we see the Space Needle in Seattle from the World’s Fair from 1962, and teams like, in Houston, the Astros of baseball or the NBA Rockets — America became space-crazed.

There’s this period of time, from the late ‘50s to the early ‘70s, where space exploration was a big part of American cultural, political and economic history.

Q: JFK himself said he was “not that into space.” It was what space represented, both as a Cold War competition and as putting down America’s marker as a technologically advanced nation.

A: First and foremost, John F. Kennedy wanted to beat the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Kennedy wanted to prove that we were building a new age of technocrats that were better than the Soviets’. But the Soviet Union had scored all these “firsts”: They had had the first intercontinental ballistic missile; the first satellite; the first creature in space with Laika, a dog; the first human in space with Yuri Gagarin, the cosmonaut.

So Kennedy was like, how do we go first? How do we leapfrog the Soviets? And Apollo was the answer: We will go to the moon, and we will galvanize and arouse democracy.

Where Kennedy deserves credit is his ability as president to sell the idea. No president has ever embraced science exploration — both the oceans and space — with the verve and insight that Kennedy did.

Q: One of the triumphs of the space program that may not have been obvious at the time was that it was taken away from the custody of the military and became a civilian undertaking.

A: President Eisenhower deserves a lot of credit for that. Eisenhower was a president of peace. But he had warned in his farewell address to the nation about an industrial-military complex.

Kennedy felt the opposite. Kennedy was very proud of the industrial-military complex. He thought it’s a great thing that Fortune 500 companies get contracts and subcontracts with the U.S. government to pioneer in space exploration, because it would be good for national security, it would be good for the American spirit and morale.

Kennedy believed space gave America international prestige, that all the world was watching this contest between the Soviets and the U.S., and if we could win that, it would convince countries in the world that democratic capitalism was superior to totalitarianism of the Communist stripe.

Q: So the message that was left on the moon, “We came in peace for all mankind,” was something that the nature of the program itself could back up.

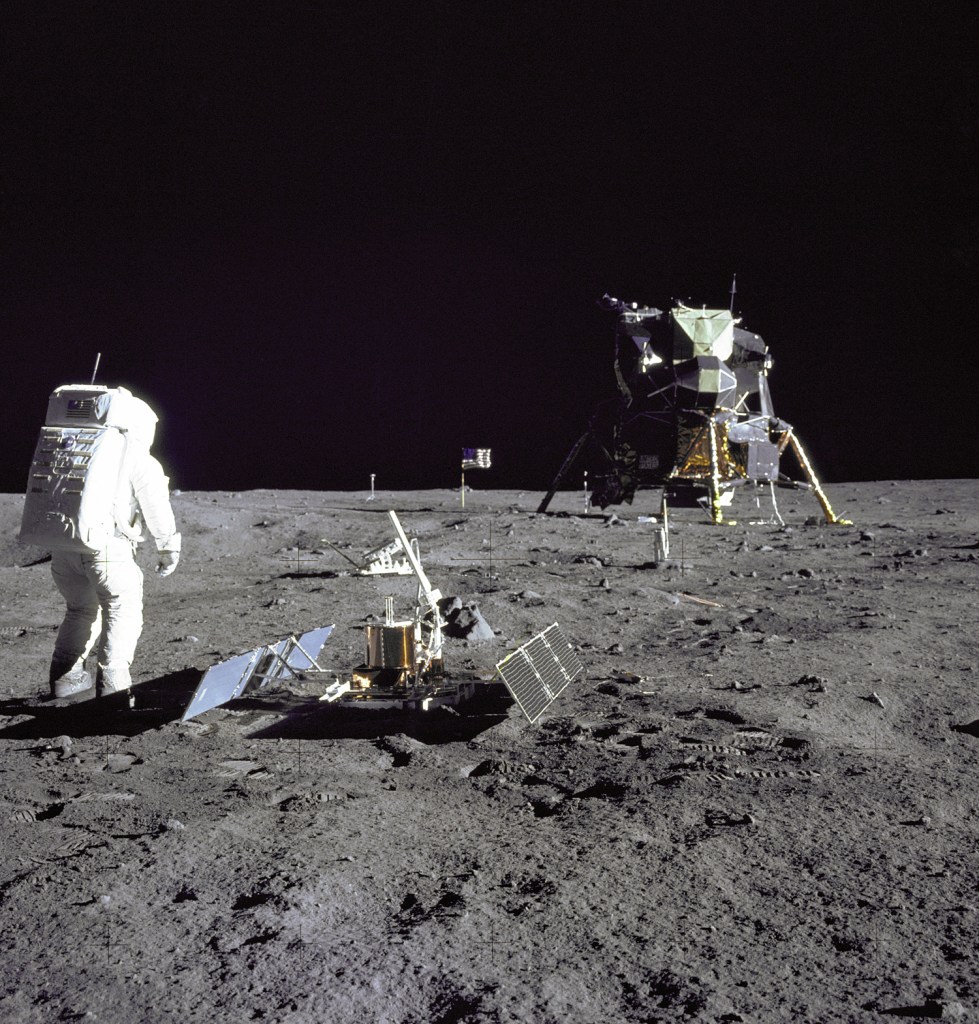

A: And also everybody focuses on Neil Armstrong’s first words on the moon, and rightfully so — “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Lesser known is that when Armstrong was leaving the moon, climbing up the ladder for the (landing module) Eagle to leave, he said to (fellow astronaut Buzz) Aldrin, “Did you leave the packet?”

In that packet are medals that commemorate Soviet cosmonauts who died in their space program, meaning we weren’t trying to gloat that we won the moon. We were there on the moon honoring even our adversaries, because we were pulling together in the realm of space.

Q: It wasn’t only the military that was unhappy about one aspect of the space program. Congress had questions about how much money was being spent. The word “moondoggle” was thrown around.

A: That was always the big question on going to the moon: how much money it cost. They used to say at NASA, “No bucks, no Buck Rogers.” Kennedy made the executive decision that $25 billion to go to the moon — that’s about $180 billion in today’s terms — was worth the price, because America would show the world the greatness of our country.

But also Kennedy had a sophisticated understanding of the spinoff technology of that kind of research and development project that the private sector would have. And indeed, out of going to the moon in Apollo, we got things like today’s GPS, anti-icing devices for aircraft, the suits that firemen use all across the country, medical inventions like the CAT scan and MRI, kidney dialysis machines and heart defibrillators.

There became a lot of benefits of the space program, so very few people question whether it was worth the money now.

The real story is, most Americans, in a bipartisan effort, said let’s do it. Because Kennedy had convinced them that it was worth it. He gave us a concrete deadline — by the end of the decade.

Q: Lyndon B. Johnson, as senator, vice president and president, was really a steward and a cheerleader for NASA and the space program.

A: Lyndon’s fingerprints are everywhere when you study the moonshot. It was one thing that Kennedy and Johnson — who didn’t personally like each other – both bought into, the idea that beating the Soviets was essential for America’s foreign policy, and neither ever really deviated from that.

Q: Budget cuts, from the Nixon administration on, really killed off much of that manned space program, did they not?

A: They did. What Kennedy did that was right was understand that America has a football-game mentality, and that you have to present winners and losers.

And so the idea of beating the Soviets made everybody want to get behind going to the moon. The problem was once we went to the moon, the box office fell off. People said, well, we’ve done that. There were other Apollo missions, and many of those missions were watched and admired but nothing like the Apollo 11 moment.

And so Nixon, by his second term, had pretty much started defunding the final Apollo missions.

We started moving into the idea of an International Space Station, which doesn’t have the drama of a blastoff and walking on the moon.

And then we had the space shuttle, which never quite took hold in the public imagination.

There have been high moments since Apollo 11. Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, in 1983. We have the Mars rovers courtesy of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. So we’re moving into Mars, but we haven’t had that moment like the moonshot when everybody is pulling forward to try to accomplish something heroic in space travel.

This 50th anniversary is sort of a launchpad of its own, to try to start winning over hearts and minds in America that we must remain No. 1 in space exploration.

Q: What do you think of the privatizing of space, almost turning it into a commercial trip where you can buy your way there and back as a civilian — and of Donald Trump’s talk about going to Mars?

A: I think with President Trump the problem is that during the Kennedy (era), NASA got 4.4% of our federal budget in the mid-1960s. Today it’s a third of 1%. If you want to do big things in space, you have to prioritize it and be a kind of cheerleader for it. President Trump thus far has shown mixed messages.

If you can somehow tea-leaf Trump, I think he’s saying we want to beat China in space; we need to get back into the game in a bigger way.

Right now, Jeff Bezos’ company Blue Origin is focused on what they call the “blue moon,” going back to the moon soon and having a colony. And (Elon) Musk is really very much about going to Mars.

So there’s a lot of entrepreneurialism going on on the 50th anniversary in the private sector, but in the end they always have to collaborate with NASA to get anything done.

Q: You grew up in the age of space, as did I. And now you’ve spent three years working on this book. What for you is the most moving moment in this whole grand story?

A: Because I grew up in Ohio, it was kind of drummed into my boyhood education the heroism of people like (Ohioans) Neil Armstrong and John Glenn. And they hold up under scrutiny. Some of these astronauts are just extraordinary human beings. To put yourself in a tin can and be shot up into space with 50/50 chances of survival — there really is a kind of raw courage that holds true.

But the other thing that I realized is, as an American historian, I probably in my career have paid shorter shrift to the world of engineering. We don’t go to the moon because of astronauts or even Kennedy. We have this engineer infrastructure, and it was 400,000 people that brought us to the moon.

There’s a lot of public happiness that America used to be able to do incredible things and work together. And now we’re in such a stark partisan divide in this country that I think the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 reminds us we do better in the U.S. when we collaborate, when we negotiate instead of dividing into enemy camps.

We’ve all been looking at the moon forever. It controls our tides and our calendar. Poets and philosophers talk about it. And starting in 1969, we visited there, we left Earth and went to another celestial body.

And it may have been the defining moment of an entire generation, the moonshot generation.

©2019 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story