BIDDEFORD — Sam Campbell was four days shy of his 18th birthday when he found himself homeless, storing his belongings at a friend’s house and trying to focus on finishing school. Some nights he had a friend’s couch to crash on, other times he didn’t.

On those nights, when he was alone with nowhere to go, he walked up and down Main Street for hours, skipping sleep. With police officers on regular patrol, it was the only place he felt safe.

“At first it kind of scared me a little, but after a while I got used to it,” he said.

Campbell, now 19 and preparing to graduate from high school, is one of more than 1,400 Maine students who are homeless and on their own. That number has more than tripled in the past several years, driving an increase in overall youth homelessness but remaining largely invisible from public view, especially in the vast majority of Maine communities with few resources in place to deal with the issue.

“It’s very much a hidden problem,” said Susan Austin, the assistant superintendent and homeless student liaison in SAD 60 in North Berwick. “The stories are heartbreaking.”

Maine saw a “monumental rise” in the number of homeless students between the 2014-2015 school year and 2016-2017, said Gayle Erdheim, the homeless education consultant for the Maine Department of Education.

The number of unaccompanied homeless youth – children who are on their own and not living with a parent or guardian – increased by 227 percent in that three-year period. There were 1,458 unaccompanied homeless youth in Maine in 2017, the most recent year for which comprehensive data is available. Nationwide, the number of homeless unaccompanied youth grew by about 25 percent, to 118,364 students.

The overall number of homeless students in Maine – including those who are on their own as well as those living with a parent or guardian – increased by 30 percent, from 1,934 to 2,515. That’s the highest number of homeless students the state has ever recorded.

While homelessness among youth has increased nationwide, Maine’s overall number grew at four times the rate of the country as a whole. The average increase was 7 percent nationwide from 2014 to 2017.

Youth homelessness often doesn’t fit the stereotypes of homeless adults panhandling on street medians, camping in woods or crowding onto mats in emergency shelters. Under the federal McKinney-Vento Act, a student is considered homeless if he or she lacks “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.” That often can mean the student is sleeping at friends’ homes or couch surfing, staying in a hotel, doubled up with another family or living outdoors.

When he was alone with nowhere to go, Campbell walked up and down Main Street in Biddeford for hours through the night, skipping sleep. With police officers on regular patrol, it was the only place he felt safe. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Many youth, like Campbell, have spent periods of time on the street before being taken in by friends or temporarily sheltered by social services agencies. Campbell said he spent multiple nights over the course of several months outside – including a few nights inside abandoned buildings – but now sleeps in a bed in a facility for young adults in Portland, riding a school bus to Biddeford twice a week as he earns his diploma.

The increase in the number of homeless students came as a surprise to both state and local school officials, who say they have never seen such a sharp rise. School officials and service providers say there is no one reason for the change, making it even more challenging to address. They say a shortage of affordable housing, families splintered by opioid addiction and mental illness, and more accurate counting of homeless students are all factors in the increase.

Some Maine communities have seen significant homelessness for the first time, while others have been facing the issue for years.

In Brunswick, the number of homeless students jumped from 14 in 2014 to 92 this year, the largest increase among public school departments in Maine.

While Portland has seen significant youth homelessness for many years, the number of homeless students more than doubled in three years as students experiencing multi-generational poverty moved in from rural towns and the city saw an influx of families arriving from Africa and seeking asylum. Such asylum seekers are not allowed to work for at least six months under federal law, and many rely on Portland’s family shelter. And in small cities and towns across southern and central Maine, schools are seeing more families struggling to find housing in their communities as rising rent prices outpace wage increases.

Sam Campbell, 19, at Shevenell Park in downtown Biddeford, where he spent nights walking when he first became homeless. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

The rapid rise in youth homelessness in Maine leveled off or paused last year, although the number remains near the record high, according to new data. Federal officials confirmed last week that the Maine total in 2017-18 was 2,444 homeless students, down slightly from the year before, Erdheim said. A national comparison for last year was not yet available.

The trend is changing how Maine school districts are serving their students. Many districts, for example, are spending more time arranging transportation for students who don’t have permanent homes, a task that can be expensive and logistically challenging, as well as trying to connect students with limited resources and fighting misconceptions about what homelessness looks like in Maine.

“Homelessness is everywhere and it looks different for everybody,” said Katie Garrity, the McKinney-Vento liaison for Westbrook schools.

SCHOOL FILLS A VOID

On a cool morning in late March, Campbell climbed off a school bus and bounded up the steps of the Alternative Pathways Center in Biddeford. His face was nearly obscured by the hood of his sweatshirt as he grabbed two blueberry muffins for breakfast and headed for his usual table.

Students work on their studies at the Alternative Pathways Center in Biddeford. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Housed in a former rectory, the Alternative Pathways Center run by the school department offers individualized education plans for students who need a smaller environment or to recover credits to graduate. There’s also a kitchen, food pantry, laundry room and closet of donated clothing.

Eleven of the 40 students in the program have been homeless at some point this school year.

Campbell comes to classes at the center twice a week, riding a school bus that picks him up in Portland and drops him off on Bacon Street in Biddeford. After months of sleeping on couches and walking the streets at night, Campbell now stays in a three-floor facility operated by Opportunity Alliance’s MaineStay program. The program has eight beds for young adults, providing shelter and support as they learn the skills needed to finish their education, find jobs and live independently.

Campbell said he had been living in Biddeford when he had to leave home over what he described as disagreements with his mother. He still maintains some contact with his family but has been on his own for more than a year. After becoming homeless, he left town for a short time to stay with a friend, but came back when he had to find somewhere else to go.

During those months when he was on the street or bouncing around from couch to couch, Campbell stayed in school, except for the weeks he missed while staying with a friend in another town.

Sam Campbell studies. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

“I preferred going to school so I had a place to be during the day,” he said. “I wasn’t roaming the streets and I had food.”

His story is similar to many of his classmates, some of whom have been homeless off and on for several years. They describe sleeping on couches, in hallways of apartment buildings and on boats during the summer. Most keep their situations quiet and try to figure it out on their own.

Brooklynn Lavigne, a 17-year-old student in the program, said she slept under a friend’s porch when she was homeless at age 12.

“I didn’t really understand it. I was sad all the time and angry at the world,” she said. “I’ve been bouncing ever since.”

Brooklynn Lavigne, left, listens as teacher Stephanie Jackson teaches a class at the Alternative Pathways Center. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

In Biddeford, the number of homeless students has doubled in the past decade, from 24 to 53, even as the overall student population has decreased. School officials say rapidly rising rent prices and evictions have left many families with young children homeless and forced to “double up” with family and friends. The number of homeless teens in the city is probably underreported by as much as 100 percent because teenagers are less likely to ask for help or identify themselves as homeless, said assistant superintendent Chris Indorf.

The increase in students experiencing homelessness has led school officials to make changes to better support students and their families when their housing situation is unstable, Indorf said. The school department distributes bags of food and has a food pantry and showers in every building for those who need them. Laundry facilities are being added to each school.

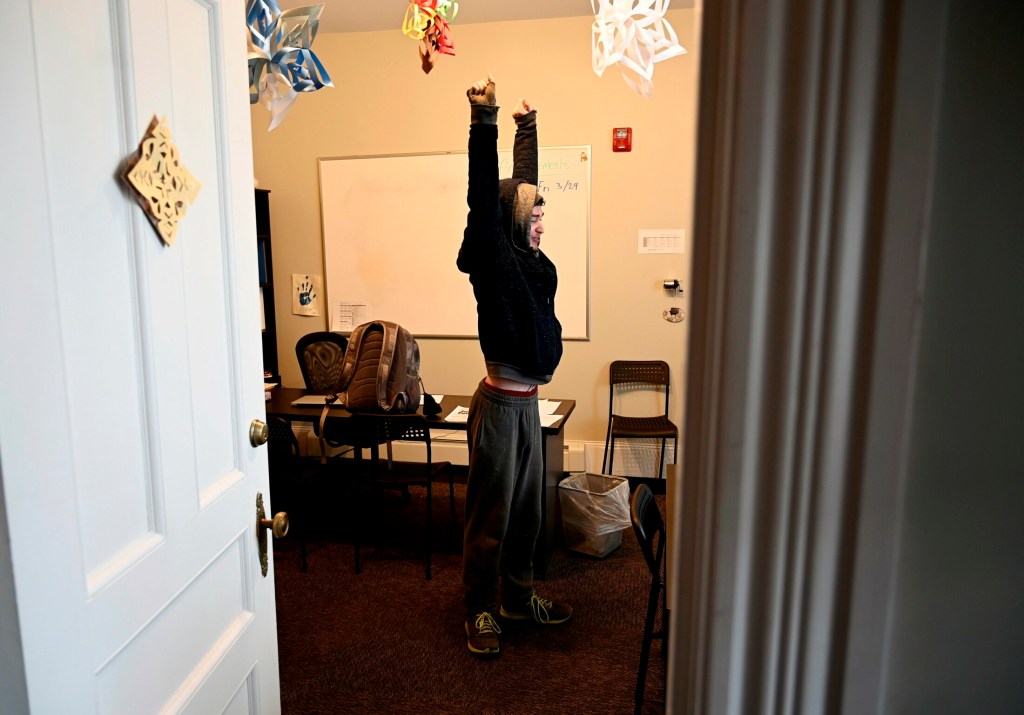

Now 19 and preparing to graduate from high school, Sam stretches shortly after arriving for class at the Alternative Pathways Center in Biddeford. He comes to classes twice a week, riding a school bus that picks him up in Portland. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

“We’ve had homeless students who don’t want to come to school because they haven’t been able to wash their clothes and have been wearing the same thing for a week,” said Martha Jacques, a social worker and director of the Alternative Pathways Center. “We’ve had students who haven’t had anything to eat other than scraps they found out of a garbage can or leftovers they found somewhere.”

School officials have been working with city officials, community leaders and nonprofits to offer as much assistance as possible and begin addressing the root causes of homelessness in the community. Part of that is making sure people understand there are homeless people in Biddeford, even if they’re not always visible on street corners.

“There’s a stigma attached to homelessness and people aren’t always willing to talk about it,” Jacques said.

SURGE SPARKS COMMUNITY ACTION

In Brunswick, there is a new focus on homelessness as the school department grapples with a dramatic increase in homeless students. In 2006, there were six homeless students in Brunswick schools. There are 92 this year – that’s 4 percent of the student population.

Greg Bartlett, the McKinney-Vento liaison for Brunswick schools, said many of those 92 students are in elementary school and come from families with multiple children. Those families are most often doubled up, temporarily staying with friends or family in other towns.

Brunswick families and students are becoming homeless for a “potpourri of reasons,” Bartlett said. He said he often hears from parents who they have lost their housing and can’t find an affordable alternative. Rising rents and evictions have become frequent challenges throughout Greater Portland in the past decade, and relatively few affordable dwelling units have been built to replace the housing that has been lost to short-term rentals or renovated for more affluent tenants.

“I know the economy is allegedly booming, but it’s booming for some people and not for others,” Bartlett said. “There is a gulf between those people doing well in our society and those people really struggling to raise their children and have gainful employment where they can afford housing. The costs keep going up and they keep falling behind.”

Under the McKinney-Vento Act, homeless students who are staying outside of the town they are from are allowed to continue going to their school of origin. That arrangement provides stability for students, but also creates a transportation challenge for districts such as Brunswick.

With more than three months to go in the school year, Brunswick schools had already exceeded the annual $10,000 budget for transporting homeless students. The school district has hired multiple local taxi and shuttle services to pick up students each day in Bath, Topsham, Freeport and other towns.

“I’m in a situation right now where if someone walks through the door today and I have to find transportation for them, I don’t know what to do,” Bartlett said.

The Brunswick Town Council recently approved a zoning change that will allow Tedford Housing to increase the capacity of both the family shelter and a shelter for single adults it runs in Brunswick. Last year, Tedford Housing had to turn away 354 individuals and 228 families.

Volunteers with the Emergency Action Network in Brunswick collected these items for homeless students in March 2018. It’s one of multiple efforts springing up in the community with the fastest growth of student homelessness in Maine. Photo courtesy of Teresa Gillis

There are growing concerns, however, about the loss of funding for the Merrymeeting Project, which provides case management for homeless teens in Brunswick, Bath and SAD 75 in Topsham. Donna Verhoeven, the Merrymeeting Project outreach coordinator, has spent 17 years providing a link for homeless students between school and other resources, making sure students are safe, and ensuring they have the support they need to finish their education.

For nearly two decades, the Merrymeeting Project has been funded by McKinney-Vento Act sub-grants, but the schools served by the project were not awarded a grant this year. Funding for Merrymeeting ends in June, as does Verhoeven’s job.

“We’re scared about that in our community,” she said.

Verhoeven said the loss of the Merrymeeting Project will come at a critical time for students as the school year ends. Summer, she said, “hits hard” because kids lose access to the resources and stability school provides.

“It’s a very vulnerable time for kids,” she said. “They lose a sense of connectivity. The springtime is the worst for these kids. They’re a nervous wreck because they can’t just drop in at school.”

TREND HITS COMMUNITIES BIG AND SMALL

When Katie Garrity became the homeless student liaison for Westbrook schools five years ago, there were four homeless students in the city. Last year, the number peaked at 120. There are 99 students who have been homeless at some point this year, but 40 who are currently homeless.

When the numbers began to rise a few years ago, “it wasn’t really on people’s radar,” Garrity said. “We really started reaching out and doing staff training and did outreach so people in the community understood they didn’t have to keep it a secret.”

For the past four years, Westbrook schools have used a McKinney-Vento sub-grant to pay for a part-time outreach coordinator to work with homeless students and their families. That has helped the district better identify homeless students and make sure they know they can continue to stay in Westbrook schools. Garrity said the stability of staying in the same school comes as a relief to both parents and students at a time when many things are uncertain.

“It’s loss after loss for these kids. It’s really sad,” she said. “These little kids go to school and try to do their best even though everything in their world has been thrown up in the air.”

In Portland, school officials have counted 348 homeless students this year, up from 202 in 2014-15. Susan Wiggin, the district transition specialist and McKinney-Vento liaison, said much of that rise is due to the arrival of asylum seekers from Africa. There are also homeless teens moving to the city from rural parts of Maine and attending Street Academy, she said. Street Academy, run through Portland Adult Education, offers education and workforce training to homeless youth.

The rise in teens experiencing homelessness is apparent at Preble Street’s Joe Kreisler Teen Shelter, one of only three shelters in the state that offer emergency housing to underage teenagers. The others are in Lewiston and Bangor.

Preble Street is on track to serve 350 youth at the 24-bed teen shelter this year and serve 17,600 meals through the drop-in center, said Leah McDonald, the teen services program director. The majority of youth served at Preble Street are between 18 and 20, but the agency is also seeing an increase in unaccompanied minors who are either new to the country or identify as LGBTQ.

Leah McDonald, the teen services program director at the Joe Kreisler Teen Shelter on Preble Street in Portland, shows a room before it fills with homeless teens for the night. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

“Most youth who are accessing our services have fled their home because it felt unsafe in some way. That may have been extreme substance abuse in the home, it may have been some sort of physical, emotional or sexual violence,” McDonald said. “They’ve gotten to a place in their life where they don’t want to be part of that anymore. These youth exhibit incredible resilience in extricating themselves from those situations.”

The average stay at Preble Street is four to six months, but occasionally a teen will come for only a night, McDonald said. The shelter is often filled to capacity and must always prioritize giving beds to minors. Recently, staff had to wake up a woman who was over 18 and walk her down to the Oxford Street shelter when a younger teen showed up in the middle of the night.

“Unfortunately, she had only a chair for the rest of the night,” McDonald said. “It’s a really difficult situation when that happens.”

TEEN SHELTERS OVERWHELMED

With only about 54 teen shelter beds available in Maine – a number advocates say falls far short of the demand – most homeless youth stay in or around their hometown. This makes it more difficult to get an accurate count of the number of homeless youth in Maine, said Thomas McLaughlin, a University of New England social work professor who has studied rural homeless youth in the state.

Sam Campbell walks the streets of Portland. He walks a lot. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Many homeless youth don’t engage in the social service system, he said, but instead “try to blend in and make it work.” They may go to great lengths to hide their situation, fearing they will cause problems for their families or be taken away from their community, according to advocates and educators.

“They’re not showing up at the food pantry, they’re not going to General Assistance,” McLaughlin said. “They’re relying on friends and community to keep them where they are.”

In rural areas where there are no shelters, school officials and community members concerned about the safety of homeless teens are setting up networks of host homes for temporary housing and finding other innovative ways to support students.

In SAD 60, the North Berwick-based school district that includes Noble High School, people are often “stunned” to find out there are homeless students in the area, said Austin, the assistant superintendent. This year, there are 47 homeless students in the district, including 33 who are in middle or high school.

“It’s pretty invisible in a lot of ways,” she said. “Kids tend to find a place to crash.”

Homeless families often tell her they have fallen on hard times financially. Other families are impacted by opioid addiction, Austin said.

Austin is spearheading efforts in the community to provide a safe place for unaccompanied students to live temporarily. A nonprofit group is working to raise money for the Ryan Home Project, which will run a home where teens can live while they’re going to school and transitioning to permanent housing.

The Ryan Home in North Berwick will be a home for homeless students in the MSAD 60 community. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

There is also a small network of homes in North Berwick, Berwick and Lebanon available for teens who need a place to stay. A similar host home is being launched by Housing Resources for Youth, a nonprofit that will match homeless teens in the Topsham, Bath and Brunswick area with volunteer host families.

Erdheim, from the Department of Education, said the host home model is fairly new across the country and just starting to appear in Maine.

“It’s an approach that is gaining traction across the country for good reason,” she said. “It’s fairly inexpensive to implement. It makes it possible for kids to stay closer to home than they would in a shelter situation. It also makes it possible to keep biological families engaged when that is the right thing to do. It seems like a really powerful solution.”

LEGISLATURE TAKES NOTE

With a growing focus on youth homelessness in many communities, lawmakers and advocates are pushing to find solutions on the state level. State lawmakers are considering two bills advocates say will address some immediate needs of homeless youth.

The first bill, L.D. 1275, sponsored by Sen. Linda Sanborn, D-Gorham, would allow homeless youth to consent to medical services without waiting the 60 days after separating from their parents, which is currently required. Advocates say this is necessary so students don’t have a gap in medical care and counseling when they become homeless.

The other bill, L.D. 866, sponsored by Rep. Michael Brennan, D-Portland, requires universities and college in Maine to designate a liaison for homeless youth, give homeless students priority for on-campus housing and develop a plan to provide housing during school breaks. The bill also expands the tuition waiver for state schools to include tuition waivers for homeless youth.

Sam vapes outside the MaineStay house where he is staying in Portland. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Educators and advocates say those bills address critical issues, but more resources are also needed to help homeless students across Maine. It can be especially difficult to help 16- and 17-year-olds who aren’t in foster care and can’t receive services through programs that serve young adults, said Jacques, the social worker from Biddeford.

Jacques was able to help Sam Campbell connect with services through Opportunity Alliance, but his temporary housing was only available because he is 18.

“The resources are great, but when a student is homeless and scared and doesn’t know where they’re going to put their head that night, waiting eight weeks isn’t a solution at that point,” she said. “It’s heartbreaking. To sit there with a student and tell them, ‘I’m sorry, we don’t have another option right now’ is frustrating.”

At MaineStay, Campbell shares this small bedroom on the third floor with a roommate. Most participants stay six months to a year and have experienced homelessness. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

On the Thursday of his April vacation, Campbell rolled out of bed just in time for breakfast with a few other teens and young adults staying at the MaineStay facility on Cumberland Avenue in Portland. He moved into the house seven months ago and shares a small bedroom on the third floor with a roommate. The program is open to youth 18 to 24 struggling with mental illness and homelessness. Most participants stay six months to a year.

Campbell is glad he was accepted into the program, but resources like this can be hard to find when you’re on your own, he said.

“Unless someone says something to you, you’re never going to find out about them,” Campbell said.

Sam Campbell, standing, second from right, attends a meeting at the MaineStay house. Resources like MaineStay can be hard to find when you’re on your own, Campbell says. Quiet and unassuming, he now organizes games with his housemates and oversees care of the program’s pet rabbit. When it’s his night to cook dinner, he often makes a family recipe for spaghetti bake. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

In Biddeford, people rarely seemed to notice Campbell was homeless when he was out on the streets. Occasionally a police officer would point out he was out after the city’s curfew, but he said that stopped when he told them he had no place to go.

“In this town, people don’t acknowledge homelessness,” he said.

Quiet and unassuming, Campbell has slowly come out of his shell during his time at MaineStay. He organizes games of Magic: The Gathering with his housemates and oversees care of the program’s pet rabbit. When it’s his night to cook dinner, he often makes a family recipe for spaghetti bake.

Campbell will graduate from Biddeford in June and hopes to go to college to study something in the computer technology field. He spends much of his free time playing and making computer games. He taught himself how to make pixel art, and his blue eyes light up when he talks about the YouTube videos he creates.

Sam Campbell makes his way down the stairs at the MaineStay house. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

On this day, Campbell has a list of errands: pick up new sneakers, a job interview, and his first apartment showing in Portland.

He’s hoping he’ll be able to find a place he can afford to move into in the next few months after he saves up some more money. Campbell left the house with plenty of extra time to stop by an office in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood to pick up a bus pass.

Walking quickly with his shoulders hunched forward against the breeze, he passed the AAA building where he took driver’s ed. Before he can get his license, he has 70 hours of practice driving to do – a tall order for someone without a family car to drive or a family member to teach him.

Campbell walks to an appointment to take his first look at a Portland apartment. He hopes to save enough to have his own place soon. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Nearly halfway around Back Cove, Campbell checked the GPS on his phone as he tried to find the apartment complex. An employee from the apartment complex met Campbell in the office to go over the prices of the various units available before showing him one.

Inside the furnished apartment, he walked slowly through each room, sizing up the space. He likes that he could have a cat here.

“It’s almost too nice,” Campbell said.

As he saves his money, Campbell plans to continue his apartment search. When he’s looking at listings, he takes note of the rent and proximity to bus stops and the condition of the appliances. But really, he’s not very picky.

“I just want a place I can call home,” he said.

Sam Campbell looks at his phone while he waits for the bus at the end of the school day. School was “a place to be” when he became homeless.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story