SKOWHEGAN — Jay Mercier, the former Industry man convicted in 2012 in what was then the oldest cold case homicide in Maine, was back in court in Skowhegan Monday morning, mounting his third appeal.

Rita St. Peter was 20 at the time of her death. Her body was found July 5, 1980, off Campground Road in Anson. Jay Mercier was convicted of her murder in September 2012 and sought a post-conviction review in 2016 after his appeal was rejected by the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. Mercier is back in court this week in Skowhegan, mounting another appeal. Contributed photo

Mercier, now 63, was found guilty of murder in the 1980 death of Rita St. Peter after prosecutors used DNA from a cigarette butt to match samples taken from the victim 32 years before.

Mercier’s lawyer in October 2018 requested new appeals in the post-conviction review process, including a request to disqualify the attorney general’s office from the case and a motion to allow new DNA analysis.

Superior Court Justice Robert Mullen dismissed the DNA motion based on the fact that the two-year deadline had long since passed for a return to evidence collected from the clothing and body of St. Peter following her murder on July 5, 1980, in Anson.

Assistant Attorney General Lara Nomani, the prosecutor in October 2018, told Mullen that the deadline for such a filing had expired in December 2014. Mullen agreed, but Mercier’s lawyer persisted, telling the court that new technology could enhance the DNA analysis and prove Mercier innocent.

The lawyer, Amy Fairfield, of Lyman, said she would present an amended petition for DNA analysis using “new modalities of testing of biological material” that would qualify to be used as evidence under the two-year, post-conviction deadline rule. She said the state had received a grant for new software to study DNA.

In February, Fairfield amended her motion again to concentrate specifically on his court-appointed lawyers in 2012, seeking to show that Mercier did not get a fair trial because of the ineffectiveness of his defense team.

Fairfield was back at Mercier’s defense table Monday, mounting an attack first on John Alsop, who had represented Mercier with co-counsel John Martin during his trial in 2012. Alsop, now an assistant attorney general, took the stand late Monday morning after a two-hour delay.

“Did you find the case insurmountable?” she asked Alsop, questioning his vigor in defending Mercier. “He put his life in your hands.”

She said in October that there is an alternative suspect in the death of St. Peter, who was 20 years old when she was last seen walking across the bridge over the Kennebec River that connects Madison and Anson late on the night of July 4, 1980. Her bloody and battered body was found the following morning on a field trail off Campground Road in Anson.

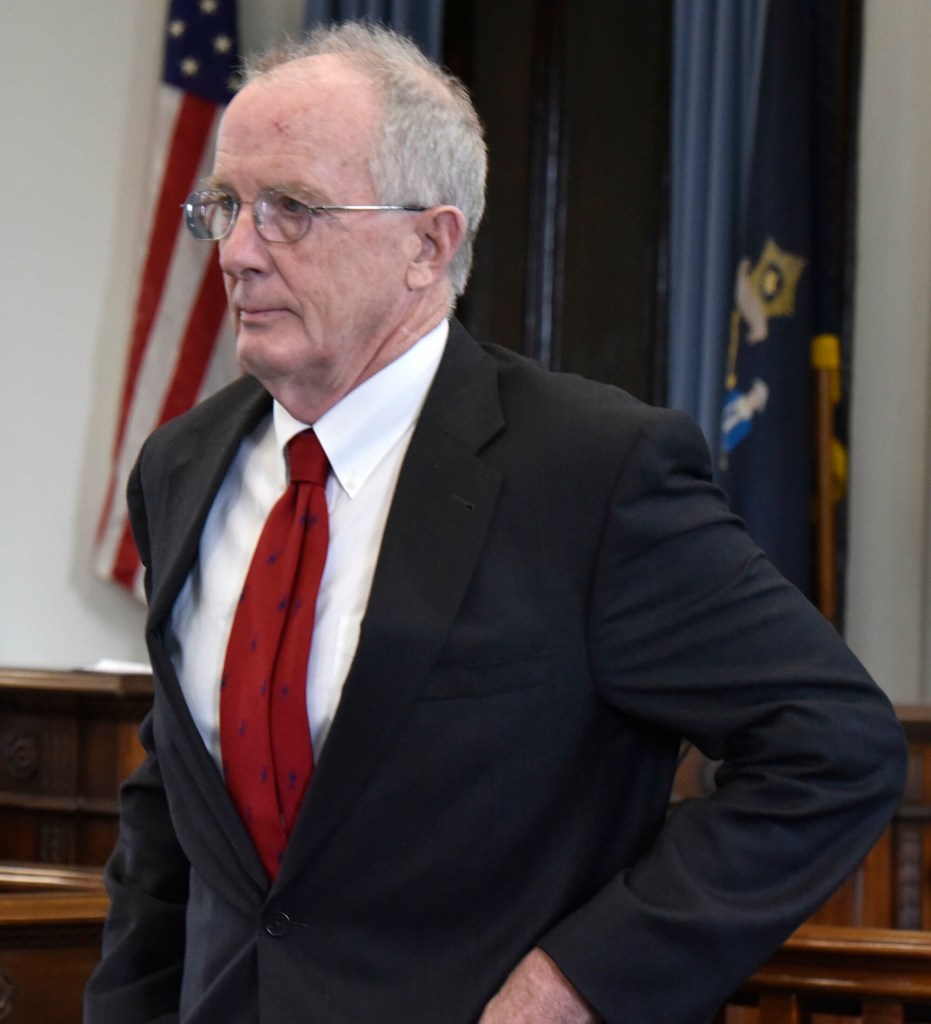

Jay Mercier sits inside Somerset County Superior Court in Skowhegan on Monday, the first day of an appeal of his conviction for the murder of Rita St. Peter. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

Fairfield wondered why Alsop and Martin did not “hire a rock star” private investigator to dig up the missing facts and evidence in the case.

There were no photographs of Mercier’s truck submitted in evidence or of the tires the state tried to use to match the truck to the crime scene. Other evidence was lost, burned or mishandled, she said. Why didn’t Mercier’s defense team try harder?

Fairfield even questioned the fact that Martin had never handled a murder trial before and that Alsop might have been too busy to give the case all he could.

On each charge against him, Alsop in court Monday countered with explanations why the alternative suspect theory would have backfired on Mercier, pointing the guilty finger directly back at him. He said he didn’t call tire experts to testify because that might have only made the state’s case stronger against Mercier.

Alsop said state police would these days have handled a murder investigation differently.

Mercier had sexually assaulted St. Peter, had beaten her with something like a tire iron, then had run her over with his truck, according to prosecutors. Sex assault charges were never brought against Mercier, a point he has raised in his request for post-conviction review.

Mercier denied killing St. Peter, but DNA evidence taken from St. Peter’s body matched Mercier’s DNA.

The St. Peter murder was the oldest cold case on the books in Maine until Mercier was arrested in September 2011. Mercier was found guilty in a jury trial in Somerset County Superior Court in September 2012.

Mercier’s initial appeal on the conviction was denied by the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in 2014. Another appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to return the case to the lower court also was denied.

Alsop said Monday before Superior Court Justice Robert Mullen that he and Martin shared all of the “discovery” material with Mercier before trial in Sept.

Attorney John Alsop leaves the stand after testifying in the Jay Mercier appeal of his conviction for the murder of Rita St. Peter at the Somerset County Superior Court in Skowhegan on Monday. Alsop represented Mercier as his defense attorney 30 years ago. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

2012 and that they left no question unanswered as they mounted their defense of Mercier.

Alsop, in his closing argument in 2012, told the jury that hard evidence had been lacking against his client. Much of the evidence had passed its expiration date, he said.

The state’s tire evidence — prints of treads found at the scene that were similar to the treads on Mercier’s truck — did not prove Mercier was at the crime scene and the fact that he had sex with her did not mean he killed her.

“We’re looking through a glass darkly,” Alsop told the jury. “We’re looking at a case that is 32 years old.”

It took about three hours for a jury to find Mercier guilty of murder in the 1980 death of Rita St. Peter.

Mercier had been a suspect from the beginning, but the case had hit a dead end. In 2005, Maine State Police Detective Bryant Jacques and Maine State Police Crime Lab forensic analyst Alicia Wilcox began their investigation of the cold case.

When DNA was extracted in 2009 from sperm cells found in biological evidence taken in 1980 from St. Peter’s body, Jacques established contact with Mercier through a series of casual conversations at Mercier’s home, according to Law Court documents from his appeal.

In January 2010, after one of these conversations, Jacques collected a cigarette butt that Mercier had discarded on the side of the road. The DNA obtained from Mercier’s cigarette butt matched that found on St. Peter’s body. Jacques later used the evidence to get a search warrant for a swab of Mercier’s mouth for a more conclusive sample.

Mercier was sentenced in Dec. 2012 to 70 years in prison.

The post conviction review hearing continues Tuesday at 9 a.m. when Martin and Andrew Benson, the prosecuting attorney in the 2012 trial, now a District Court judge, are expected to be called to testify.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story