The mother of missing Waterville toddler Ayla Reynolds and her attorney are asking a Cumberland County court for more time to serve the child’s father with a wrongful death lawsuit after efforts to locate Justin DiPietro over the last three months have yielded no results.

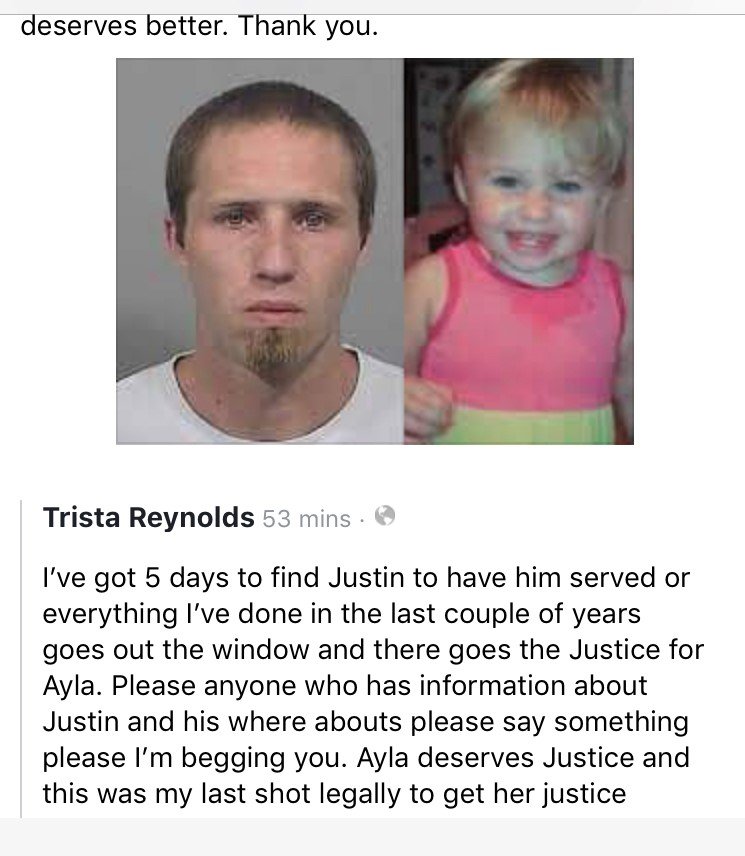

The move comes after Trista Reynolds, mother of Ayla Reynolds, filed the lawsuit in December accusing DiPietro of being at fault in their daughter’s death in December 2011.

Ayla Reynolds, who was 20-months-old at the time, was in DiPietro’s care and was last seen at her paternal grandmother’s house before she was reported missing.

A judge in 2017 officially declared Ayla to be dead, paving the way for the civil lawsuit, which Reynolds’ attorney William Childs said in December is intended to help answer questions about what happened to Ayla and possibly recover her remains.

Authorities never brought up charges but have said they believe Ayla met with foul play and that DiPietro did not disclose all he knew. Before he moved away from Maine in the years after his daughter’s disappearance, DiPietro maintained someone must have abducted her during the night.

In court documents filed Wednesday, Childs said an extensive search to locate DiPietro, including the use of private detectives in Maine and California, visits to his last known addresses and searches of electronic databases and government records have not worked.

He and Reynolds have 90 days from the time the suit was filed to serve DiPietro the paperwork. That deadline falls on Sunday, and now the two are asking Cumberland County Superior Court for more time.

In a Facebook post Tuesday, Trista Reynolds wrote, “I’ve got 5 days to find Justin to have him served … Justice for Ayla. Please anyone who has information about Justin and his where abouts please say something please I’m begging you. Ayla deserves Justice … ”

Reynolds did not respond to a phone call seeking comment.

On Wednesday, Childs asked the court for an additional 60 days to locate DiPietro and recommended serving him by publishing an order for service in newspapers in Maine and California, the state where DiPietro was last known to be living; mailing a copy of the order for service and summons to DiPietro’s mother’s home in Waterville; and leaving a copy of the court’s order, summons and complaint at DiPietro’s last known residence in Winnetka, California.

If those things are done, Childs said the lawsuit can proceed to the discovery phase regardless of whether DiPietro responds or acknowledges the suit.

The documents filed Wednesday include affidavits by private investigators in Maine and California and a Kennebec County Sheriff’s Office deputy talking about their extensive efforts to locate DiPietro.

Kevin Cady, a licensed private investigator in Maine, wrote in one affidavit he was able to locate a possible address for DiPietro in Winnetka but couldn’t find anything more current after searching social media, criminal records in all states, driver’s license information, professional licenses, vehicle information, property deeds, hunting and weapons permits and other records.

Nelson Tucker, an investigator in California, attempted to serve DiPietro at the same Winnetka address found by Cady, but when he arrived, he was advised by one of the current tenants that DiPietro had moved out in July 2018.

Tucker then searched social media, online telephone directories, a criminal index for the state of California, medical facilities and hospitals in Los Angeles County, post office records and other databases with no luck. Tucker performed the searches in December and again in February, still with no luck.

A third affidavit by Allen Wood, a deputy sheriff with the Kennebec County Sheriff’s Office, also says he tried to serve DiPietro at his mother’s home at 29 Violette Ave. in Waterville — the same home Ayla went missing from — and was informed by Phoebe DiPietro that her son didn’t live there and hasn’t been there for two years.

Wood wrote he also checked with the Waterville Police Department, which has not had contact with DiPietro since May 2012.

Asked how rare it is to be unable to locate someone to serve them with court documents, Childs said “it’s not unheard of” and pointed to the fact the court has a form specifically designated to showing due diligence in serving someone in person and providing for alternative service, such as by newspaper.

“If there’s a form, you can assume there’s a necessity for the form,” Childs said. “It happens. People go off the grid, and it’s hard to find them. If someone works under the table, pays cash for their apartment or they don’t have a driver’s license, they can be hard to find. If you don’t want to be found, you can go off the grid.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

rohm@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story