This happens pretty much every year. By the beginning of March, there is so much snow plowed up around the yard we feel like we’re living in a crater. From there, it only gets weirder.

To enter the driveway from Route 9, you pass between two large, pointed piles of snow. The ice-covered gravel track, such as it is, descends at what seems to be the same angle of slope I remember when I started into the Pyramid of Khafre in Cairo years ago and had to turn back. It bends down over Bog Brook like a sort of miniature causeway, lined in winter by snowbanks, and bottoms out under snow-laden pine, maple, oak, cedar and other branches that close out low-angled winter sunlight and leave the ice there two to three miles thick, or so we estimate. The driveway becomes a sort of tunnel. It then re-ascends for about 50 feet and comes out in the yard, which this past weekend was encircled by 7-foot mountains of plowed-up snow. Welcome to Crater Troy.

If you look at these steep walls too long you start to feel uneasy. They’re covered with rocky-looking frozen debris and peaked with boulders you imagine must be the same on the slopes of K2. The walls are all moon-ice white, closing off the world.

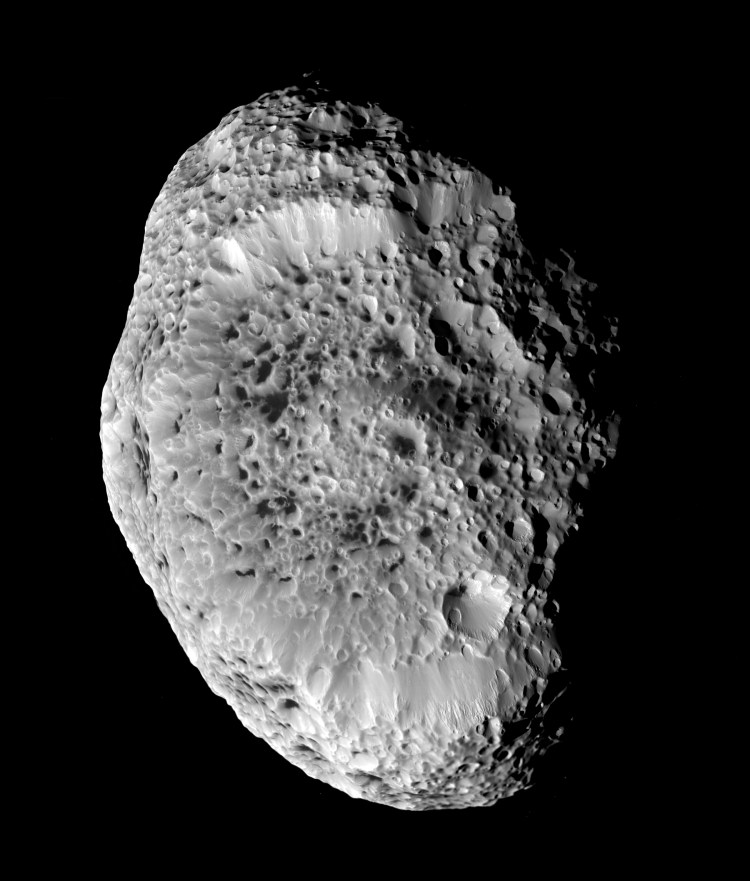

Last week, I was standing in the middle of this driveway nowhere, looking up at the ice walls, and started thinking I’d seen this before. Rubble-strewn snowbanks or maybe glaciers, surrounding me. I wasn’t sure if it was from a childhood memory or a dream or another lifetime. Trying to remember was like clambering along an underground passage. Then suddenly I was up the other side: The driveway crater is an exact similitude of Saturn’s weird moon Hyperion.

Hyperion is a potato-shaped thing around 224 miles long and 128 miles at its widest point. It’s made mostly of ice. A spacecraft photo shows a huge crater gashing almost one whole side of it. The crater slopes are bright and steep and seem rubble-strewn. There are scores of other craters in the crater, with jagged-looking edges. It could be somebody’s driveway in Troy.

How Hyperion got that way is essentially unknown. It could be the last big chunk of a larger moon that got blown apart in a collision or in a bombardment that Saturn’s environs are thought to have undergone eons ago. But Hyperion (named at the time of its discovery in 1848 after one of the Titans, about whom not a lot is revealed in ancient Greek texts) has other shadowy inexplicabilities, too. For one thing, instead of rotating smoothly and evenly like other moons and planets, it tumbles chaotically end over end and side over side. It orbits Saturn every 21 days near the much larger moon Titan, which makes three rounds for every four of Hyperion’s. Every time Hyperion passes into Titan’s gravity, it jostles, changes its spin axis and flails.

Hyperion’s density is so low its interior is thought to be a webwork of ice caverns. If somehow you could make your way through its constantly skewing 13-day spin and set foot on it, not only would you be standing at the bottom of winter looking up at ice walls, but you might also descend through openings in the craters to minus-300-degree caves. You might crawl down shadowy tunnels and find frozen debris and tinkling landslide motions you wouldn’t think possible. If you stayed down there long enough in that titanic darkness, you might eventually wonder if it was an actual place or just a piece of winter tumbling end over end for the rest of eternity, or at least until the next bombardment of snow and ice. After a long time of freezing, you inhabit this feeling of craterous remoteness and claustrophobia you want to crawl out of, and can’t.

Winter lasts so long here, and its walls are so steep, and cold, and your mind, it wanders in.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. You can contact him at naturalist1@dwildepress.net. His recent book is “Summer to Fall: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods.” Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story