SKOWHEGAN — After historic Coburn Hall in the heart of downtown Skowhegan burned to the ground in December 1904, it was replaced with a new building, constructed on the site the following year, in 1905.

That building, with entrances on Water Street and what is now called Commercial Street, eventually housed Skowhegan District Court and law offices upstairs, with a lunch counter and pharmacy on the ground floor.

The District Court moved to a new building in 1997, leaving all of the original wooden stairs, doors, wainscoting, transoms and fine trim work right where it was.

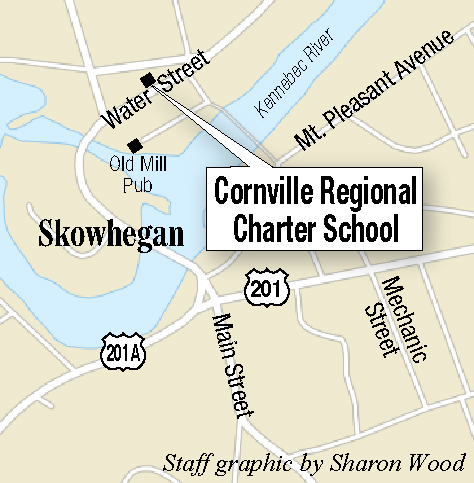

When the Skowhegan Planning Board approved the site plan for a high school annex to be operated by the Cornville Regional Charter School in February 2017, that’s what they found — a dusty, but largely untouched, piece of history ready to be restored.

Enter Travis Works, executive director of the charter school.

“We have the original plans for the building from 1905,” Works said during a tour of the downtown school this past week. “This is all original — the district attorney’s office, lawyers offices. We went back to every detail that we could. We kept everything as original as possible. I think it’s important when we look at culture. History is a really important piece for the community, and it’s really important for us to preserve that.

“It’s really easy to build a new building that’s just plain, but to have that come into a sense of history and identity is really important. All too often, it’s easy for us to forget those different elements, especially with buildings here in downtown. So we’re looking at restoring the outside of the building to bring it back to the 1905 look.”

Cornville Regional Charter School student Lydia Dore, of Athens, walks past historic acorn stair posts Feb. 11 on the second floor at the school’s renovated downtown property in Skowhegan. Classrooms have been renovated, and students will replicate the posts for new staircases in the building. Morning Sentinel photo by Dave Leaming

Even the original entry way into the building from Commercial Street, which back then was known as Russell Street, has been restored to the original size and location.

That section of Water Street is called the Merrill Block, for the law offices of E.M. Merrill, which were on the second floor next to the district attorney and around the corner from the courtroom.

The 1920s seating in the old district court that had been donated by Lakewood Theater in the 1970s remained in place until renovations began after the charter school purchased the building in 2017. The rows of seating are still there, now gracing the entrance to one of the eight classrooms on the second floor of the school.

Lydia Dore, a 10th-grade student from Athens, said she appreciates the importance of preserving the original building.

“It’s an awesome building that we have, and I so enjoy it,” she said. “I think it’s awesome that we’re trying to keep as much of it original, as it was, as a way to keep history. We are taking that into consideration, and we’re trying to restore that. I think people are kind of forgetting about this. They’re forgetting that a big thing in our community is still here.”

Students moved into space in the former Holland’s Variety Drug in August 2017 in downtown Skowhegan, opening a high school annex for the original Cornville Regional Charter School.

The charter school, which opened as Maine’s first elementary-level charter school in 2012, was given state approval by the Maine Charter Commission in December 2016 to add a charter high school and pre-kindergarten classes to its program.

The downtown Skowhegan campus is for students ages 12 and older, studying at their ability level in grades 7 to 10 this year. Next year it will go up to 11th grade, with 12th grade added the following year, according to Works.

Travis Works, executive director of the Cornville Regional Charter School, talks about the renovations and preservation of historic architecture at the school’s downtown Skowhegan property on Feb. 11. Works is on the second floor, once occupied by the Somerset County Courtroom, which will become classrooms. Morning Sentinel photo by Dave Leaming

Works noted that, in the style of a charter school, the classrooms will not be designated in grade levels for high school, such as the conventional 10th, 11th and 12th grades, but will be organized according to advancement of students ages 12 to 20.

The elementary-level charter school is organized in the same way for students ages 5 to 14, so there will be some overlap between the two campuses, Works said.

There are 90 students attending classes in the downtown campus, with 140 at the original campus in the former Cornville Elementary School and 45 in the early childhood campus on South Factory Street.

A charter school is a public school that receives public money but is created and operated by parents, teachers and community leaders, free of the rules and regulations of the area school district. Charter schools are open to all regional students, with no additional tuition fees or admissions tests. Teachers touch on everyday skills — including cooking, knitting, gardening, technology, engineering and woodworking — along with classroom lessons based on Maine’s Common Core of Learning.

Public schools receive some of their funding through the state. The rest comes from local taxes.

Travis Works, executive director of the Cornville Regional Charter School, talks about the renovations and preservation of historic architecture at the school’s downtown Skowhegan property on Feb. 11. Works is on the second floor, once occupied by the Somerset County Courtroom and District Attorney offices, which are now classrooms. Morning Sentinel photo by David Leaming

“We don’t have that option,” Works said of local taxes. “We’re restricted by the state subsidy.”

Works said Cornville is a free public school; it cannot charge tuition. When a child enrolls in a charter school, the state money that normally follows that child comes directly to the charter school from the state. It does not come out of the local public school district. There also are state education programming grants that all schools get and the town’s revolving loan fund.

The annual operating budget for the combined campuses is $3.5 million.

On the ground floor of the downtown campus, where the business offices are, is a busy work place for teaching and learning career and technical skills, which Works and his students say can be applied to everyday life in and out of school. There are power tools and clamps and vices and work tables in what will be a fabrication lab and graphic arts studio.

There is a 54-inch, wide-area printer being used under the direction of Crystal Priest, the teaching principal and technology director of the Skowhegan campus. 3-D printers are being built by students, and there is a laser engraver for wood, plastic and metals.

Students also are repurposing the building’s original 1905 wooden floor joists into frames for windows on the second floor, where the study classrooms are.

Hailey Pelletier, a ninth-grader from Skowhegan, said her group was learning how to use the different power tools, including sanders and a jig saw.

Cornville Regional Charter School students occupy renovated classrooms in former lawyer offices in the school’s downtown Skowhegan property on Feb. 11. Morning Sentinel photo by Dave Leaming

“Learning this can apply to what people would like to have as a job in the future,” she said.

Works agreed, noting that hands-on learning is a critical piece of a child’s education.

“No matter what they do in life — whether they’re a doctor, a lawyer or they go into a trade — for them to understand and have knowledge of all these different pieces is critical,” he said. “We can utilize this equipment here for small, local businesses, so if we have a business with one or two employees, they can use these. It becomes a shared resource.”

Works said there are three key pieces of the downtown Skowhegan campus: community members sharing their talents and knowledge with the kids; community members learning side by side with the students; and sharing school space with members of the community.

Construction work is being done by Brian Frigon and his BNF Building Contractors, of Moscow. Engineering is being done by Steve Govoni, of Skowhegan.

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

dharlow@centralmaine.com

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story