This week November has already started to leak over into December and look like winter. There’s a crust of snow already edging our backyard inside the woods. This is kind of unusual, for recent years. November has always, and especially lately, had more of a distinct late-autumn personality, different from any other month, really.

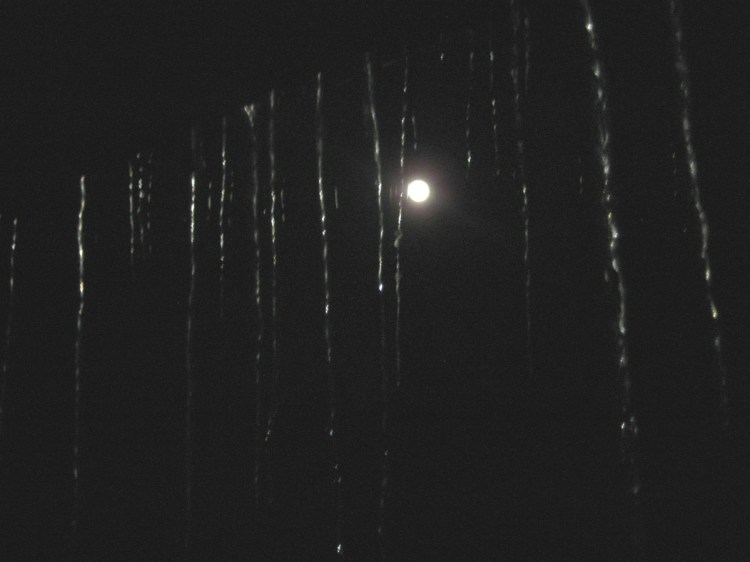

Not sure why, exactly. They all bleed into each other to one extent or another. But in November, something about newly bare trees distinguishes the whole sense of the world from before Halloween, which is one thing, and from December, which is another. The trees in this deer-hunting span look like a tangle of gray skeletons. Some marcescent leaves stand out, mostly oak brown and beech dull, and the tamaracks have gone to yellow flares. They stand there, to quote an old rock ‘n’ roll song, and seem for all the world to be just patiently waiting for what’s inevitably to follow. The Farmers’ Almanac calls a full moon in November “beaver moon.” Abenakis call it “freezing river maker moon,” according to one academic source; and the Passamaquoddys, “freezing moon.”

This year the freezing wetness feels like December descending early. It’s usually after Thanksgiving, sometimes well after, when nights start to go cold for good, by which I mean consistently below 30. This is because of lowering sunlight, lower and lower for shorter periods every day. The Farmers’ Almanac calls a full moon in December “cold moon” or “long nights moon”; and the Abenakis, “winter maker moon,” which sounds exactly right to me. The Passamaquoddys have “frost fish moon,” which is outside my reckoning, really, never having been an ice fisherman.

If November is bare and December is the beginning of the end, January and February are the deep freeze itself, with distinctions maybe less obvious than November’s skeletons from October’s colors and December’s hardening. In January the junipers are shagged with ice, which in normal times never really lets go, and the spruces look rough in the distant glitter of the low winter sun. January is the mind of winter, maybe summed up in names like “wolf moon” or the Passamaquoddys’ “whirling wind moon,” if you see what I mean.

In February the cold bites that much deeper and wider, so you get full moon names like “starvation moon” and “snow moon.” Abenakis also have “makes branches fall in pieces moon,” and Passamaquoddys, similarly, moon “when the spruce tips fall.” But something else intensifies February that is almost impossible to notice in the ice of January, and that’s that the sun, which has been grinding only very slowly higher in the sky, begins a steep upward swing in mid-February. March can still be cold at night but starts to thaw in the elevating sunlight, so lunar apparitions get names like “worm moon,” because life is starting to emerge from underground; and Passamaquoddy, simply “spring moon”; and Abenaki, “spring season maker moon.”

But despite the tidy, one-to-one, month-to-moon-name charts you can find online and in books, reality is something quite different. The months have certain recurrent characteristics, but in truth they often do not fit neatly into preconceived categories. Month-naming is a human-made illusion. The moon haunts the very word: Two thousand years ago in Northern Europe, “month” referred to a complete moon cycle from new to full, which lasts a sliver more than 29 days. Time-keepers narrowed the named months down to 12 a year, but since all but one of our months has 30 or 31 days, it turns out there are usually 13 full moons — 13 months — in a calendar year.

So when the chart tells you that “harvest moon” or “corn moon” means September’s full moon, or that “hunter’s moon” means October’s, or that “beaver moon” is November’s, the chart is cheating. For Abenaki and Passamaquoddy people, phrases like “freezing moon” are not, from ancestry immemorial, talking about a period of time called “November” at all. They’re talking about full moons that occur during a condition of the seasonal round.

In what might be more accurate expressions, a Penobscot website calls the full moon corresponding to a full moon in maybe late October or November simply “moon of autumn” (takʷαkəwí-kisohs). A full moon appearing in the 31-day span we cling to calling December is “moon when ice forms on the margins of lakes” (asəpáskʷačess-kisohs).

I like this a lot better. It looks just like the beaver pond up the road around this time of year. It relieves the burden of wondering why December is horning in on November, which is not a “month” at all, but a state of mind. A time of a moon of autumn, a freezing moon, a waiting for winter moon. I love the skeletal trees, the somber gray and brown, the yellow tamaracks, the way they recur and settle in. The stillness here is all.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. You can contact him at naturalist1@dwildepress.net. His recent book is “Summer to Fall: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods” available from North Country Press. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story