You wouldn’t know it from TV, but most court cases never go to trial.

More than nine times out of 10 they are resolved through plea deals, settlements or mediation or are decided by a judge as a matter of law.

But for those few cases where there is an actual dispute over facts that can’t be worked out between the parties, a trial by jury is still the gold standard for determining the truth.

Jury verdicts carry special weight in our society: They set markers that guide the rest of us in ways that a settlement rarely does because the terms are usually confidential. And when a criminal defendant is found guilty by a jury, there is a sense that the community has spoken.

A trial by jury is one of our most treasured rights, and in a country without a military draft, jury duty is one of the most important obligations of citizenship.

So, if it’s so important, why don’t more people show up?

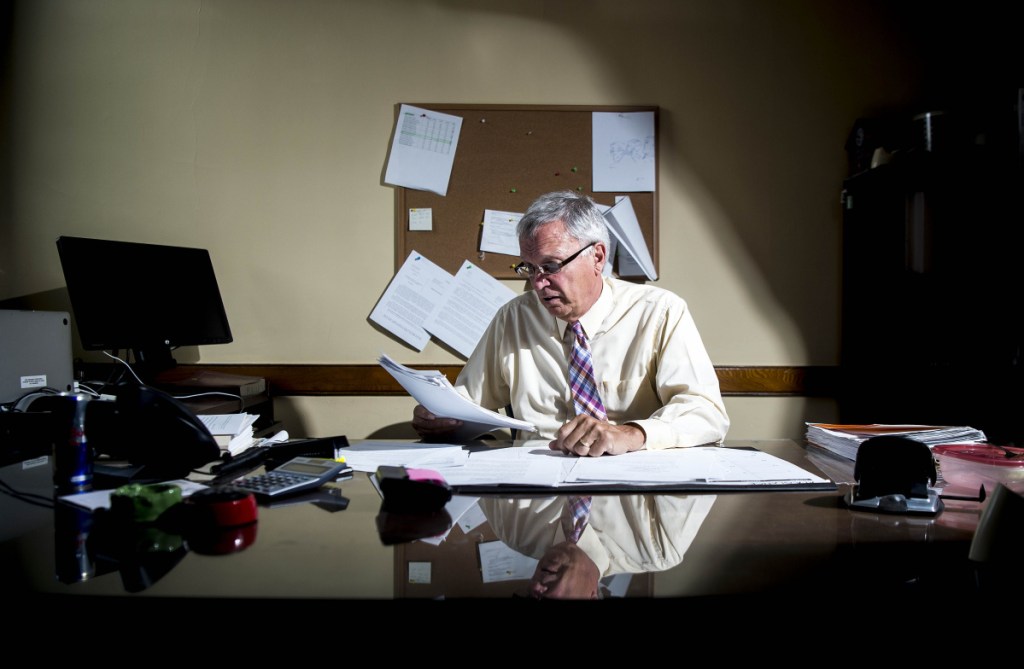

The scofflaw problem has gotten so bad that Superior Court Justice Robert Mullen in Somerset County has taken to ordering some of the absentees into his courtroom to answer a few questions. If they don’t appear for that, they could face a fine or even jail time.

“The law is the law, and I think some people need to realize that there are some teeth to back up their duty to serve if they don’t come and they don’t explain why,” Mullen told the Morning Sentinel, and he has good reason to be concerned. He’s worried about having enough jurors to conduct trials, forcing people to wait for their day in court. This is a problem not just in Skowhegan or even Maine, but part of a national trend where people ignore the call for jury service.

Civics lessons like the one Mullen has in mind might solve part of the problem, but there are structural issues that also need to be addressed.

In Maine, jurors are paid only $15 a day for service in state court. While some work for employers who keep them on the payroll while they are in court, contract workers and small-business owners who get paid only when they are actually working stand to lose quite a bit of money. Jury service shouldn’t be a path to riches, but it shouldn’t be a financial hardship, either. It especially shouldn’t be a financial hardship for only some potential jurors.

Judges are right to make sure that jurors show up when they are called, but the Legislature has a role to play here as well.

Only $15 a day is not enough to compensate people who are asked to put their lives on hold for the good of the community. And advanced communications technology should give potential jurors a way to comply with their summons remotely, and come into court only when they are being assigned to a trial.

If jury trials are going to continue to be less common, we need the remaining few to run smoothly.

For that to happen, we need to make sure that more people can afford to serve.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story