LISBON — When campaign experts asked Republican gubernatorial candidate Garrett Mason last year if he had any skeletons in his closet, the Lisbon lawmaker laughed.

Mason, 32, said he didn’t have anything to worry about.

Then he added that there was this one thing, and proceeded to tell them an astonishing tale about a man he’s never met, an aging ballplayer who lives outside Los Angeles.

This is the story about that man, and the Mason family, and the curious path that chasing a dream can take – and the price it can extract.

Let’s begin with a critical caveat: Whatever else he is, Richard Pohle is not always a straight shooter.

The 79-year-old Lisbon native’s version of events, delivered in rapid fire over the phone and captured in news stories for more than four decades, has a way of shifting over time to become ever more cinematic, with Pohle himself cast as the star of the show.

Years ago, believe it or not, there was talk of Al Pacino playing him in a movie.

And even though much of Pohle’s tale is about baseball – always fertile ground for those with a gift for gab and a tenuous grasp on the truth – it is also about a family back in Lisbon that includes two state legislators, one of whom hopes to be elected governor in November.

Garrett Mason, a state senator, is one of four gubernatorial candidates in the June 12 Republican primary. He has never met Pohle, though they did speak on the phone once a few years back. Mason’s father, Rep. Rick Mason, R-Lisbon, has no memory of the man.

Garrett Mason, 32, is vying to be Maine’s youngest governor. Pohle is his biological grandfather, though the men have rarely spoken. Pohle gave Mason’s father, Rick, up for adoption and ultimately chose to pursue a career in baseball, with mixed results.

What makes that noteworthy is that Pohle is Rick Mason’s biological father. Pohle is Garrett Mason’s biological grandfather. He is also a guy who pursued playing professional baseball rather than raise his son, whom he gave up for adoption before heading south to greener diamonds and year-round sun.

“I’m not saying I did everything right,” Pohle said in the recent telephone interview, calling his choice at age 19 “one of the worst mistakes in my life.”

He often doesn’t sound like a man with many regrets, however.

After all, he spent his entire life in the game he loves – as a player, a scout and a coach – and even got a chance to play professionally.

In the two games he played – at the rock bottom of the minor leagues – Pohle got a hit, scored a run and stole a base. He also committed an error and struck out. It’s all there in the record books.

What makes it notable is that he played his first professional game at the age of 36, and he did it under an assumed name, Rocky Perone, a make-believe Australian who called everyone “mate” and wore a shaggy black wig. Pohle’s manager in Walla Walla, Washington, thought he was 21, the oldest player on the team.

When Pohle later helped at least five other ballplayers secure professional contracts by faking their ages in the years that followed his own foray into the minor leagues, the San Francisco Examiner dubbed him “baseball’s perennial flim-flam man.”

Pohle’s vagabond baseball saga is so bizarre it has landed him in the pages of Sports Illustrated, the Los Angeles Times, ESPN and more. It is cited frequently as one of the great hoaxes in sports history.

BEGINNINGS IN LISBON

It began on the fields of Lisbon, where Pohle played for the high school team, the Greyhounds, and also for a couple of community teams. By age 16, the wiry shortstop had already attracted at least a little national attention. He knew he had a shot at the big time.

The early 1950s, he said, were “the best era you ever want to live in,” a quiet time when an occasional beer was about as rowdy as anything got.

But there was this girl. He was 18, a senior. She was 17, a year behind.

Pohle said he dropped out halfway through his senior year in 1957, and “got married and had a baby,” a boy they named Rick.

That didn’t stop Pohle from heading to Florida for a tryout camp with the Washington Senators, where he played in front of coaches impressed enough to urge him to head to Nova Scotia for summer ball.

Pohle instead returned to Lisbon to work in his father’s meat market.

By then, the young woman he left behind had figured out what he already knew: “I didn’t want to stay married. I only wanted to play baseball.”

So they split.

“I didn’t know nothing about life and neither did she,” Pohle said. “I was embarrassed by the whole darn thing.”

She didn’t want him to see the baby, but a friend who watched baby Rick while his mother worked let Pohle sneak in each day to see the boy – until the sitter got fired for it.

Before long, the mother had taken up with Paul Mason, a classmate at high school. They married in 1959.

One day a sheriff’s deputy showed up at the market with legal papers that indicated that the mother wanted Pohle to give up his parental rights and let Mason adopt the boy.

Pohle didn’t like the idea, but he said his father convinced him it would mean an end to paternity payments and might be best for Rick as well.

“At least he’ll have a father,” Pohle remembers his dad telling him.

So he signed.

Pohle said the only time he saw his son again was during recess at a grammar school in Lisbon, when a teacher stood with Pohle beside the playground and pointed out the boy. She told him Rick was “very bright.” Pohle recalls him wearing glasses and winter boots.

They never spoke, he said, and he’s had no contact since.

“I had no connection to the family at all” after Mason adopted Rick as a baby, Pohle said.

BASEBALL COMES FIRST

During their teenage years, Garrett Mason and his sister were told by their parents about the adoption. He said he listened and then headed out to a practice.

“We just found out and moved on,” he said. “This happens in families.”

Pohle said that a few years ago Garrett Mason phoned him “out of the blue” in California, curious to find out about the biological grandfather he knew mostly through the words of sportswriters.

Pohle said Garrett, by then a state lawmaker, “sounded like a very nice guy.”

The truth, Mason said, is that Pohle had tried to call him for years, perhaps trying to cash in on whatever celebrity a state legislator possesses, angling for someone to push that elusive movie deal. Mason ignored the calls for a long while.

Finally, though, during a trip out West, the lawmaker said he “kind of got the nerve up to talk to him” so he dialed the man’s number.

“I had questions,” Mason said. “I wanted to know the story” by then and to understand the decisions that Pohle had made “just for my own peace of mind.”

Pohle said they talked about baseball – Mason once worked for the Portland Sea Dogs – and about what happened many years before the future state senator was born.

Pohle said it blew his mind to learn he had a grandson so involved in politics. But Pohle said he was happiest to find that his grandson had a history with a baseball club and a hockey team.

“You’ve got my blood in your veins,” Pohle said he told Mason.

Both Mason and Pohle confirmed that they didn’t meet while Mason was in California because the older man had already promised to introduce a young player to a college coach during the only available meeting time.

Once again, Mason said, Pohle had put baseball first.

“He’s made it so easy not to be curious,” Garrett Mason said. “A father is a relationship. And he chose to have a relationship with baseball.”

Mason said he also realized Pohle couldn’t really enlighten him.

“That question of ‘why’ can never be answered. And we don’t need it to be answered,” Mason said.

FATHERS, SONS AND GRANDFATHERS

When Pohle talks he sometimes mixes up Garrett and Rick, conflating the decades between them, perhaps unable to grasp fully that his baby boy is 60 and his grandson about half that.

Pohle said he told Garrett during that phone call that “I only regret one thing: that I couldn’t bring you up and be a father to you.”

Pohle phoned the Sun Journal in May after reading its profile of Garrett Mason, who’s aiming to become the youngest-ever elected governor.

He said the piece left out a key part of the Mason story – Pohle himself.

Both Rick and Garrett Mason scoffed at the idea.

“It’s interesting that he thinks he’s part of our story when he hasn’t been an ounce of it,” Garrett said.

“He’s not my grandfather. My grandfather is Paul Mason,” who took in his father when Pohle left to play ball and raised him as a part of the family in every way.

“That is my father: Paul Mason Sr.,” Rick said. “He taught me how to live. Being a father is more than biology.”

Rick said he misses his father, who died a year ago, and credits him for instilling a strong work ethic and passing along a fount of wisdom.

“Dad was always there for me,” Rick said. “He treated me like one of his own.”

The Masons are a close-knit family, bound together in faith and affection.

Recently, Rick proudly stood atop a rock wall he built in the backyard shortly before his wife, Gina, died last September. He pointed down to a stretch of freshly seeded turf beside a pond.

It’s a pretty spot, one that Rick and Gina Mason created over the years by clearing the land together. It’s the place where Garrett plans to get married in a couple of months, surrounded by family and friends.

It’s one field that Pohle will never set foot on.

THE UNDENIABLE CALL OF BASEBALL

Pohle has taken the baseball field in quite a few countries, including Australia, and hung out with coaches and scouts most of his life. He burrowed deep into the heart of the game and operated a baseball school in Orange County, California, with another son, one he didn’t leave behind.

Yet one bad break after another left Pohle just shy of the goal that motivates so many youngsters who have a good swing, speed and the ability to snag a hard grounder.

The pros would check Pohle out, then leave him behind, convinced the 5-foot-7-inch ballplayer didn’t have the size or skills needed.

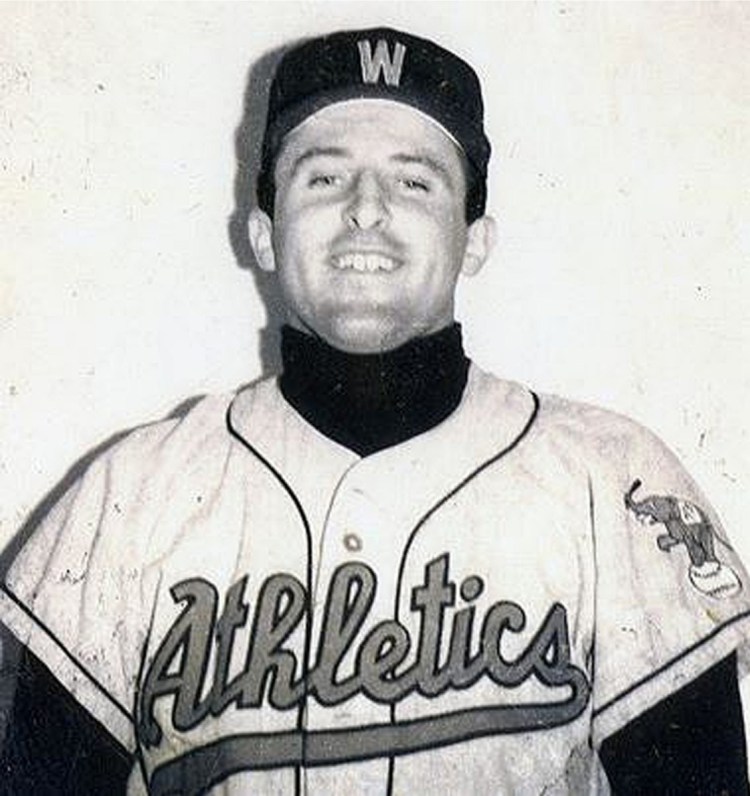

Once, when Pohle was 26, a Kansas City Athletics scout saw him play in Oxnard, California, and asked him about signing a contract.

Pohle told the man he was 18 because he knew nobody wanted a prospect on the downside of his 20s.

They brought him to a training camp in Florida where he hustled to make it big in front of manager Bobby Hoffman. Instead, though, he pulled a hamstring and got released, Pohle said.

When he told the story to ESPN a decade ago, he didn’t mention a hamstring pull. In fact, he said he thought he’d made the team until Hoffman called him into his office, handed him an envelope and wished him luck.

In Pohle’s telling, he took a train back to Los Angeles, arriving in the middle of the night. He walked 6 miles to his sister’s home, where he found “parking tickets all over my car.”

Despite the setback, Pohle told himself “I’m not quitting” and kept making the rounds, playing everywhere he could in semi-professional leagues that offered reasonably high-quality baseball.

HOW THE HOAX WENT DOWN

Let’s pick up the tale at age 36, long past the time for all but a handful of professional baseball players.

Pohle decided to try one last time to convince scouts he had what it took, that he could play with the pros.

He said he phoned “a big fat scout” for the San Diego Padres, Jim Marshall, and pretended to be an importer from Australia. He told Marshall to check out a kid from Sydney, Rocky Perone, because the guy had what it took.

They arranged a tryout for the supposed 21-year-old.

“I had to do something. I wasn’t some rinky-dink from Pipe Dream City. Over the years, I’d proved myself repeatedly. I had to prove myself again just to be here. I’d had to show them something. The hoax about my age was just a device to get the scouts to look at me, to really look at me,” Pohle explained in a 1979 account for Sports Illustrated written by Eliot Asinof.

Pohle said he donned a wig, old sweatshirt and a Dutch Boy painter’s hat, trying to look terrible in a bid to make sure nobody actually scrutinized him too much.

He ended up on a field at Florida Southern University in the spring of 1974, with college players snickering at his appearance.

Pohle said he proceeded to the plate and “put on a hitting show” that quieted them. He had the speed and the fielding prowess to go along with it, he said.

Marshall agreed to sign him, setting a 2 p.m. meeting for the next day.

That night, in one of many wild asides, Pohle says the guy in a downstairs apartment had country music blaring at 3 a.m., so Pohle marched to the man’s screen door to ask him to lower the volume.

Pohle said they wound up outside, the small ballplayer versus a drunk giant. Pohle said he shattered the guy’s jaw but broke his thumb in the process. Police and ambulances showed up, he said, and two hours later he had a cast instead of a contract.

After driving one-handed down the road to his room, he said, he realized he had to get the cast off, so he spent hours sawing through the wet plaster to remove it.

His arm, Pohle said, was “like a balloon” and turning blue to boot.

But he managed to sign the contract, Pohle said, and then headed out to find a doctor to replace the cast.

In his long 1979 version of his life experience for Sports Illustrated, though, Pohle didn’t mention his broken thumb.

In June, two months before Richard Nixon resigned as president in 1974, Pohle – masquerading as Perone – showed up in Walla Walla, using Swedish skin cream to keep his face supple and the Pete Rose-style wig to hide his graying, thinning hair.

“I nearly died during spring training,” he told the Associated Press a year later. “The wind sprints were awful. But I stuck it out. I was determined to get into a game, to have it on record.”

When he finally got a chance to take the field in a game, in Lewiston, Idaho, he worried that “the jig might be up” when he realized the opponent’s manager was Hoffman, who had known him a decade earlier in Florida.

He got to play, earning a base on balls and then stole second, something he knew would wind up in the records of the statistics-driven game.

Pohle had done it. He was, forever more, a professional baseball player.

“It was the greatest feeling in the world,” he once said.

In later stories, Pohle strongly hints that Hoffman recognized him. But he told the Associated Press the manager didn’t remember him.

Two days later, the Walla Walla Padres released him. He told the AP they let him go to make room for a new draft pick.

The AP said that Mike Port, the Padres official who approved the contract, admitted that “he conned us, no question about it. The guy really is young-looking.”

Port, who ended up as the head of umpiring for Major League Baseball, said Pohle “can’t play ball. We could see the first day of camp that something didn’t add up.

His reactions and movements were poor. But we didn’t suspect he’d lied about his age. He didn’t have a chance of making it, but since he’d driven all the way up here, we let him play in a game.”

Pohle eventually got a chance to play one more game, with the Salem Senators in Oregon, after Sports Illustrated featured his saga five years later. It was just a lark, but it, too, is in the record books.

EXTRA INNINGS

Was it all worth it? For Pohle, the answer is surprisingly clear.

At the end of a short movie about him that aired at a Los Angeles film festival in 2010, “The Secret Life of Rocky Perone,” Pohle looks into the camera and tries to sum it all up.

“I’ve been playing ball for all my life,” he said. “I lived my dream.”

His advice to others?

“If anybody out there has a dream, keep your dreams. Live your life that you think is best for you. Live your dream.”

Maybe it’s just as well.

“I’m happy with the way things turned out,” Garrett Mason said. “We wish him well. We have our family.”

scollins@sunjournal.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story