Two years ago, citizenship classes in Lewiston would be packed with 40 or 50 recent refugees to the United States eager to learn English and pass their citizenship tests. Today, those classes draw only five or 10 students.

“We don’t have new refugees coming here,” said Rilwan Osman, executive director of Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services.

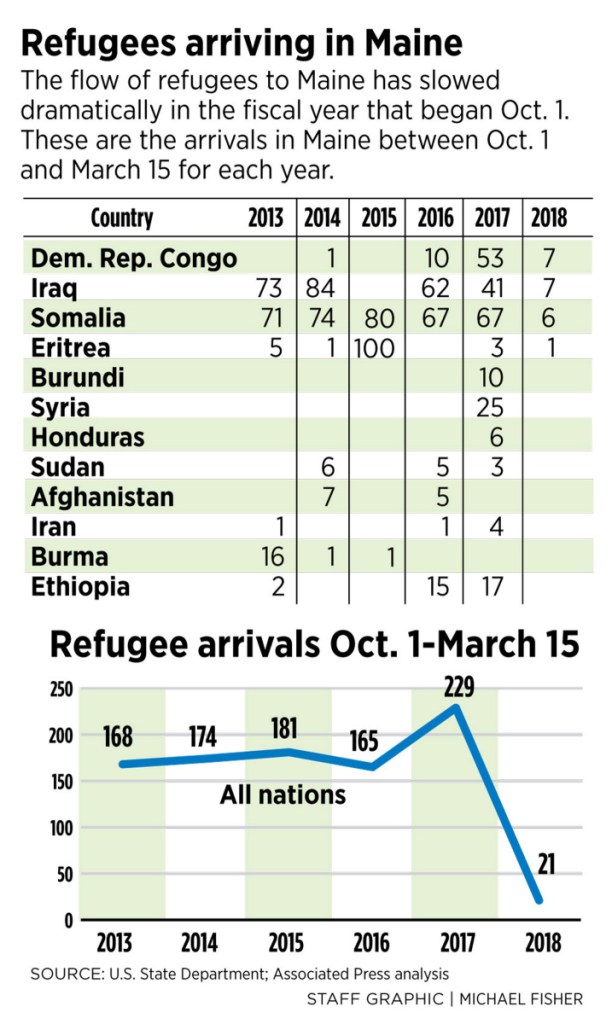

The flow of new refugees arriving in Maine has slowed from a steady stream to a trickle in the past six months, part of a national trend driven by a variety of restrictions imposed by the Trump administration.

A data analysis from the Associated Press shows the U.S. is on track to accept the smallest number of refugees in the 38-year history of the modern resettlement program. At the current rate, the U.S. will take in about 21,000 refugees this federal fiscal year, less than half the cap of 45,000 set by the Trump administration. About 85,000 refugees came to the United States in 2016 under the Obama administration.

The decrease has been even more pronounced in Maine.

Catholic Charities Maine, the state’s only refugee resettlement agency, expected to receive 375 people this year, a significant drop from the 642 refugees resettled in Maine last year. As of Thursday, more than halfway through the federal fiscal year, the organization has resettled just 30 refugees so far.

The AP analysis found that 21 refugees arrived in Maine between Oct. 1 and March 15, down from 229 during the same period a year ago.

“Maine was particularly hard hit by the travel bans,” said Hannah DeAngelis, program director for Refugee and Immigration Services at Catholic Charities.

That’s because Maine has traditionally received a large percentage of its refugees from Muslim-majority countries affected by the new Trump administration policies and bans, DeAngelis said. The state has accepted 77 refugees from Syria since 2014, but no one has arrived this year. In recent years, hundreds of refugees have come from Iraq and Somalia – the two most common countries of origins for refugees in Maine – but the number of new arrivals from each of those countries was less than 10 as of earlier this month.

Maine refugee arrivals, by year and by nation of origin:

Note: Data is for the first part of each fiscal year, from Oct. 1 – March 15.

Interactive: Christian MilNeil

Refugee status is a designation given by the United Nations to people who have fled their countries because of persecution, war or violence.

Refugees receive assistance from the United Nations while waiting to qualify for resettlement, a process that takes years. Once resettled in the U.S., refugees are eligible for federal cash assistance for up to eight months.

Nearly 4,000 refugees have settled in Maine since 2002, and the majority are from Somalia and Iraq.

Courts struck down the first two versions of the travel ban ordered by President Trump. Those were replaced by the current ban, which places varying levels of restrictions on people from eight countries – Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, North Korea and Venezuela. Some exceptions are allowed, such as documented business purposes or close family relationships. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to make a decision about the legality of the ban in June.

Trump also has restricted programs that allow immigrants to bring their family members to the U.S. Among them is a program that allows families split during refugee resettlement to be reunified. That was suspended last year and then restarted in response to a judge’s injunction, according to the AP.

More than 70 percent of the cases at Catholic Charities Maine are family reunifications, DeAngelis said. Family reunification is also called “chain migration” by those, including Trump, who want such access to be more limited.

The changes have affected an unknown number of families in Maine who had been working to bring relatives here.

“People expect their family members to join them here in Maine,” DeAngelis said. “There’s a number of legal avenues to petition for that to happen. Many have been stopped. I think people are very anxious about those processes, and there’s very little information about when those will begin.”

Even in cases where refugee resettlement is allowed to continue, the slowdown could also be attributed to new security procedures established by the latest travel ban, DeAngelis said.

“What we’re mostly hearing is that family members are going through the security screening processes over again,” she said. “Family members in Maine are feeling very discouraged.”

The process of refugee resettlement is already a difficult one. Osman, who was born in Somalia, came to the United States in 2004. His application was in processing for three years while he lived in a refugee camp in Kenya.

“It is a long, expensive process to come here,” Osman said. “A lot of screening, a lot of interviews from one agency to another. It took me a long time.”

Mahmoud Hassan, president of the Somali Community Association of Maine, said refugee admissions have become “a small trickle.” He said he knows many community members are waiting for relatives who seemed to be approved for immigration to the U.S. Now, their applications have been put on hold.

“There were always interviews, there were always processes, there were always questions,” Hassan said. “But then, if people had done all the right things, it was expected that they travel. But that expectation is not there anymore.”

As the number of refugees coming to the U.S. shrinks, so will the resettlement system. The administration has told executives of nine private resettlement agencies they must close any office expected to place fewer than 100 refugees this year.

Catholic Charities Maine had expected more than 300 arrivals, so it was not affected by that directive this year. But it has made cuts to case managers as the flow of refugees dropped off. DeAngelis said the office lost the equivalent of five positions over the past year – about 20 percent of the staff.

“We’ve been trying to retain our staff and expertise as long as we possibly can,” DeAngelis said. However, she said, “We weren’t seeing a trend up again in refugee resettlement.”

She said the organization did resettle one family from Somalia last month. But the future is uncertain.

“I don’t know if that is indicative of future cases getting through,” she said. “It’s unclear if it’s going to be months or years for those families.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story