AUGUSTA — These days, getting around isn’t simple for Paul Allen. He can’t afford a car, so to get to his job at the McDonald’s restaurant on Bangor Street, he must throw on his high-tops and camouflage jacket, then walk more than a mile from his apartment on Chapel Street.

Allen, 29, uses the sidewalk when he can, he said during a recent interview on the side of State Street, just north of Memorial Circle. But when it snows heavily and the sidewalks become miniature mountain ranges of ice and slush, he’s often forced to walk in the breakdown lane.

About two weeks ago, Allen said, a passing car even struck a bag of bottles he was carrying up the shoulder of Western Avenue, spilling its contents.

“People yell, ‘Use the sidewalk!'” he said. “I’ll point to the sidewalk and say, ‘What sidewalk?'”

Winter can be particularly dangerous — even deadly — for those who must get around on their feet, on bicycles, on wheelchairs, or via any other mechanism that doesn’t feature an internal combustion engine and a large steel frame.

No pedestrian deaths have yet been recorded in Maine in 2018, but a flurry of pedestrians were killed by cars at the end of 2017, making it the state’s deadliest year for pedestrians in more than a decade.

While this week’s warmer weather has made a small dent in the overall snowpack, transportation experts warn that the peril continues for those who rely on sidewalks, shoulders or what’s left of them.

“We’re kind of in peak season where pedestrians are at the greatest risk,” said Patrick Adams, the manager of bicycle and pedestrian programs at the Maine Department of Transportation. “Not necessarily because it’s snowing outside, but you’ve got sloppy conditions with snow, slush and ice out there. We know we’ve got large snowbanks, which are blocking off sidewalks and in many cases narrowing the roads.”

Adams defined that season as the months from November to March, when pedestrians must negotiate the mounds of snow and might be forced into the road. He also noted that drivers might have less control of their vehicles in the snow, or might be less likely to see or avoid pedestrians when the daylight is limited.

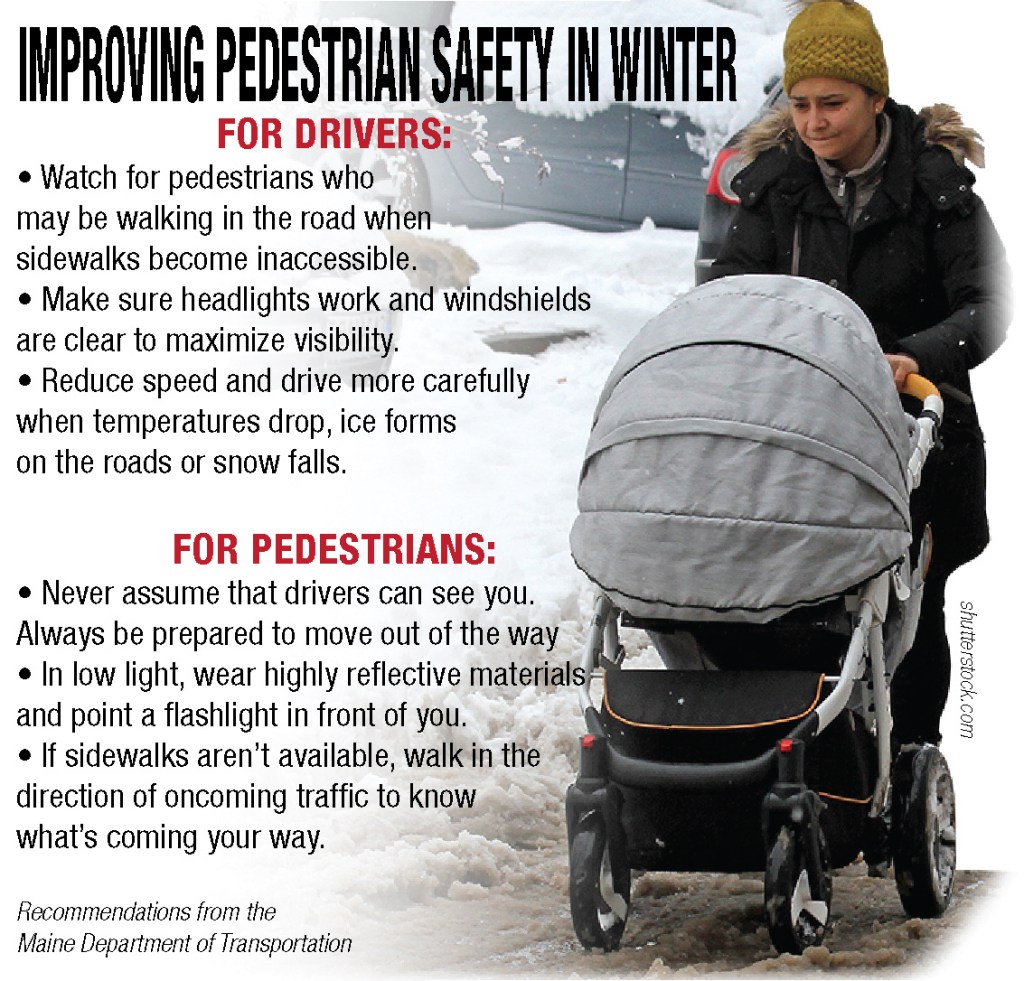

Following the spike in pedestrian deaths in recent years, the transportation department has partnered with the Bicycle Coalition of Maine to educate pedestrians and drivers about safer walking and driving practices, such as wearing brighter clothes, walking against the flow of traffic, and being extra cautious when driving in poor weather. There’s no single factor that has led to the spike, and Adams said the project’s goal is not to place blame on either pedestrians or drivers.

But some pedestrians take a more cynical view of the risks they face. They argue that communities place too much emphasis on plowing roads, at the expense of vulnerable populations — the poor, the elderly, the handicapped — who rely on the neglected sidewalks.

Allen is well aware of the dangers facing pedestrians like him. In a recent conversation, he criticized drivers who aren’t careful when passing walkers. He also said the city does a “terrible” job clearing sidewalks.

He was walking with Megan Brown, of Augusta, who said that her cousin doesn’t walk outside after its snows because she has cerebral palsy and can’t keep her balance in the slippery conditions.

In the last five years, there has been more demand in Augusta for clear sidewalks, according to Lesley Jones, the city’s public works director.

The city has tried to meet that demand by adding a new sidewalk clearing machine into its rotation, bringing the total number to three, and Jones instructs workers to picture how suitable sidewalks are for walking when they clear them.

But the city is limited by the fact that it must plow 154 miles of road before focusing on the 30 miles of sidewalk that it clears, as well as the fact that the public works staff is small and workers require rest as they spend days responding to a snowstorm, Jones said. They also can’t clear a sidewalk too early, as snow that’s plowed from the roads will just cover it a second time.

“If (the workers) need a rest, they go home for a bit; and as soon as we can, we schedule three machines to go out and do the sidewalks,” Jones said. “It’s the same people who plow the snow who do the sidewalks, and we can’t stop and do the sidewalks until the storm is done. We appreciate people’s patience.”

The sidewalk tractor, Jones added, “is a complex little machine with a blower, and if they hit obstacles in the sidewalk, a chunk of a pavement or a stone or a bag of trash, or something that someone has dropped off, it can mess that blower up.”

Jim King, who lives near downtown Winthrop, has heard similar arguments, and on some level he understands them. But he also thinks they reveal the limits of a community’s concern for the vulnerable.

Because King is blind, he often walks to the store, the Town Office and other places with the guidance of his German shepherd. When there is snow on the ground, going places takes longer, he said, because the dog must find new routes.

Sometimes, when fed up with the obstacles, King just leaves the sidewalk and walks around the edge of the travel lane, at danger to himself. While most drivers are courteous and will slow down for pedestrians, he said that some have expressed their frustration with him.

“Winthrop is no different from any town, but my general feeling is, first of all, I understand the common assumptions that we have to keep the traffic flowing,” he said. “But when we do that at all costs, at the expense of pedestrians, then we are alienating or ostracizing a significant portion of the society from being able to participate in community activities and other personal things that have to happen.”

King also noted that some residents and business owners do clear their sections of sidewalk.

But the willingness of people to do so — or the willingness to require them to do so — can be limited. Another Kennebec County town, Belgrade, recently considered an ordinance that would have given commercial property owners 12 hours after it snows to clear their sidewalks, and 24 hours for residential property owners to clear the sidewalk after the state or town finishes its cleanup.

Selectmen rejected the ordinance in a 3-2 vote, in part because some residents opposed the sidewalk requirement.

There are no state or federal laws requiring municipalities to clear sidewalks, though Maine DOT does have “the expectation” that communities will clear those surfaces, said Adams, the manager of the state’s pedestrian and biking programs.

Adams also said communities can’t clear snow from every road and sidewalk at the same time and must prioritize the order in which they do so.

But one of the goals of Maine DOT’s ongoing campaign, Adams said, is to get communities to consider which sidewalks get heavy foot traffic and could receive higher priority after a snowstorm.

Staff Writer Betty Adams contributed reporting.

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story