A wealthy musician and a refugee mother don’t have much in common, but each of them has a son who was poisoned by lead dust in a newly renovated Maine home. This is how lead poisoning looks in Maine: renovations of old houses and low-income rentals. While a recently implemented Maine law that lowers the acceptable blood lead level is certainly a proactive piece of public health legislation, it did not and could not have prevented these two typical cases of lead poisoning.

A Dec. 29 editorial called for the lead law to be used as a model in reducing our exposure to another toxin — arsenic in our drinking water — but I believe that a more comprehensive approach to the risk assessment and intervention of a home’s health is the real solution. We have the laws, the people and the tools, but we need to ensure collaboration, communication and consistent financing so that Mainers have healthy housing.

Blood lead testing is one tool to identify that lead hazards exist in a child’s environment and begin medical intervention when necessary. But let’s be clear: It detects, not prevents, lead poisoning while, ideally, lessening the impact on a child’s health.

The Maine law lowered the threshold to start intervention from 15 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood to 5 micrograms, aligning it with the federal standard. Researchers estimate that lead-poisoned children lose 2 IQ points for every 10 micrograms per deciliter that their blood lead level rises; an increase in blood lead from less than 1 microgram to 10 micrograms is associated with a loss of 6 IQ points. The societal and financial costs to American families and communities are astronomical.

Would it outrage you if policymakers suggested testing children rather than wells for arsenic? It should outrage us as parents, as Mainers and as real estate consumers that federal and state legislation has accepted the use of children as lead testers rather than insisting on environmental testing before owners market residential units for sale or rent. It should really outrage us as taxpayers that federal and state housing subsidies are used to house vulnerable families in unhealthy rental units in Maine while the property owner (and financial beneficiary) faces virtually no pressure to provide lead-safe housing until after a child is poisoned.

Jon Fishman, the drummer for the band Phish, has spoken publicly about his family’s experience with lead dust in a 200-year-old Lincolnville farmhouse. Fishman told The Huffington Post in 2015 that he suspected the lead dust was created by stripping the floors during a renovation or cleaning the house without a HEPA filter. His wife runs an organic farm. While they were limiting their exposure to chemicals in food, their family was exposed to a neurotoxin at home.

The contractor who renovated the Fishmans’ farmhouse was required by federal law to have Environmental Protection Agency lead-safe certification. This requires an eight-hour class for renovators who work in residential buildings built before 1978 to learn how to contain and clean the poison. The contractor either didn’t have certification or didn’t follow the lead-safe work practices, and Maine has neither an EPA office nor agency staff to oversee compliance.

The family of refugees rents a two-bedroom apartment in Westbrook that is undergoing lead abatement, funded by a federal Lead Hazard Control grant. The building was constructed around 1900, and all the tenants receive rental assistance.

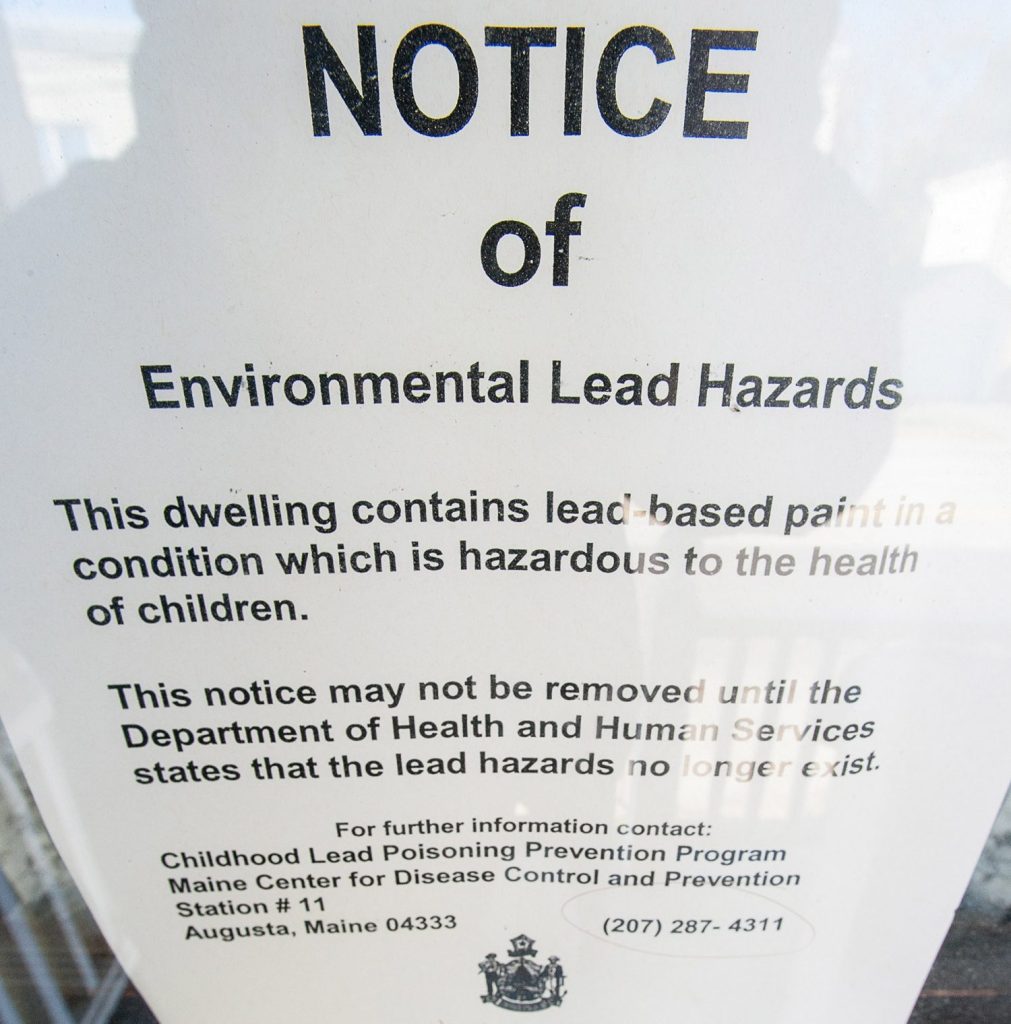

The poisoned child had previous health problems, including a behavioral condition where he eats substances that aren’t food. You can’t see lead dust, but housing authorities don’t require lead inspections, so the unit passed multiple housing inspections and was approved for the family. The lead hazards were detected long after the child was exposed, and his level was well over 5 micrograms.

We have made progress in reducing the number of lead-poisoned children, but these two cases of lead poisoning in Maine highlight the continued gaps in our protections of our future. The solutions seem obvious. Test houses, not kids. Encourage residential mortgage lenders and insurance companies to require lead risk assessments and factor the cost of lead remediation into their underwriting processes, so the market can respond and build capacity in lead remediation. Reform insufficient building and rental codes to address potential health hazards through code enforcement and permitting processes, which will involve shared resources and expertise with public health officials. Whether the toxin is lead or arsenic, there is no excuse in 2018 for Maine children to be poisoned in their own homes.

Colleen Hennessy is the former Lead Hazard Control grant manager for the city of Portland and a part-time faculty member at the University of Southern Maine School of Social Work. She can be contacted at colleenhennessy.com or on Twitter:@colleenhenness4

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story