Lawyers battling over the legitimacy of Anthony H. Sanborn Jr.’s 1992 conviction for the murder of Jessica Briggs questioned one of Sanborn’s original attorneys Monday about a bedrock issue in the case: What did Sanborn’s legal team know, and when did they know it?

Sanborn’s current lawyer, Amy Fairfield, directed questions at attorney Edwin Chester aimed at showing that police possessed, but chose to exclude from their reports, information gathered in the field that would have helped Sanborn’s defense.

But Assistant Attorney General Meg Elam tried to show during her cross-examination that some of the underlying claims that triggered the post-conviction review – including that police pressured witnesses to implicate Sanborn, and some claims about the eyesight of an eyewitness – were known to Chester before the trial, and therefore cannot be used to overturn Sanborn’s conviction now.

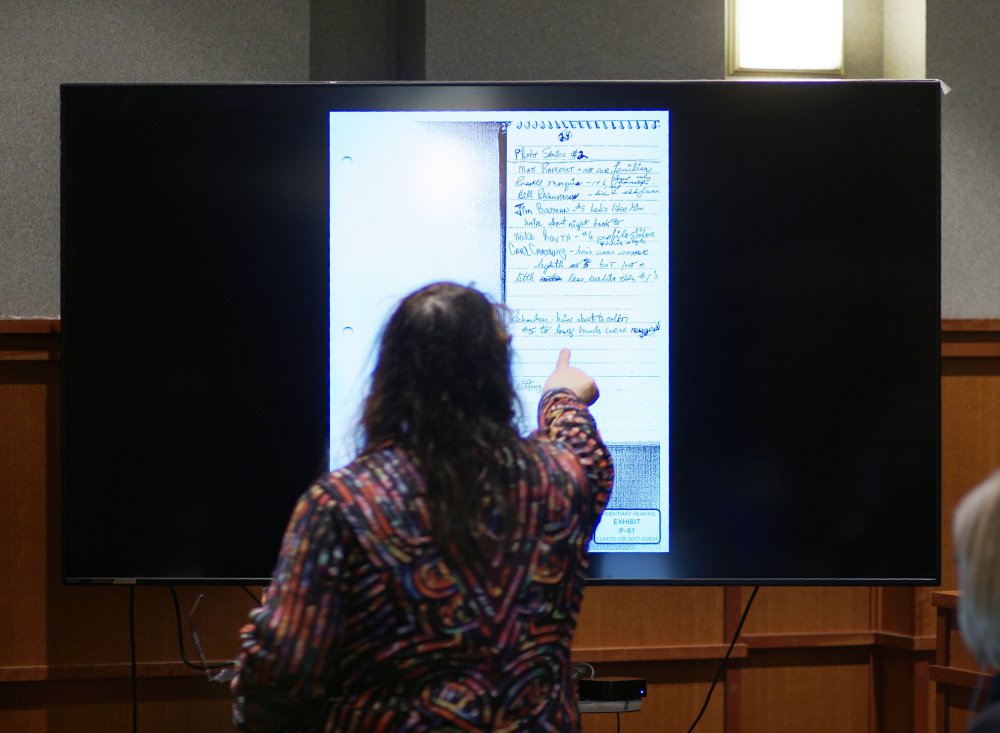

Much of the material that Fairfield drew from came from the two boxes of handwritten notes and other documents that were stored at the home of retired police detective James Daniels, the lead investigator of the Briggs homicide, after his retirement from the Portland department in 1998. Daniels turned them over in the spring of 2017.

Chester, along with attorney Neale Duffett, represented Sanborn after his 1990 arrest, through early hearings that determined he would be tried as an adult, in Sanborn’s appeal of the bind-over decision transferring him to adult court, and during his criminal trial in Portland Superior Court.

The post-conviction review case hinges on whether the state withheld information from Sanborn’s lawyers that could have helped his defense. Justice Joyce Wheeler, who is overseeing the case, must determine whether the allegedly withheld facts, had they been known to Sanborn’s lawyers nearly three decades ago, would have more than likely led to a different verdict.

After he was found guilty, Sanborn was sentenced in 1993 to 70 years in Maine State Prison. He was freed on bail in April after the only eyewitness in the case, Hope Cady, recanted her testimony. Cady also said in April that she had difficulty seeing, and that she had always struggled with vision problems – a fact that Sanborn’s lawyers allege was known by the state but never disclosed.

Fairfield asked Chester about an incident in 1991 when Cady reported to her social worker that she saw Sanborn on a beach in York County. He had been arrested and was in jail at the time.

“If she’s identifying someone as Tony Sanborn when it couldn’t be Tony Sanborn, that would have been useful evidence,” Chester said. “It would have likely become a part of our cross-examination of Ms. Cady.”

How about her eyesight, Fairfield asked.

“It might have raised that issue as well,” Chester replied.

On cross-examination, Elam tried to undermine Chester’s reliance on his records to determine whether something had been given to him or not, and seized on the fact that Chester turned over his case file to a journalist, John Rudolf, who has been independently investigating the Sanborn case for years.

Elam showed during questioning that Chester’s list of documents did not match a list of discovery materials that the state handed over to him. Elam also honed in on conversations that Chester had with witnesses, including Sanborn’s wife, known then as Michelle Lincoln, who told Chester that she felt pressured by detectives.

Elam also called Chester’s attention to a note dated around the time of Sanborn’s trial written in Chester’s handwriting and pulled from his own file, describing a conversation he had with a caretaker of Cady, who told Chester that she believed Cady had vision problems from cocaine use.

“I think the document says, ‘cocaine, arrow, detached retina,’ ” Elam said. “What would your arrow mean?”

“I’d think they’re related,” Chester said.

Testimony by Chester is expected to continue Tuesday.

Correction: This story was updated at 9:19 a.m. on Nov. 8, 2017 to correct the name of the assistant attorney general.

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story