BALDWIN — It’s a crucial part of Andrew Clements’s job to clearly recall what it felt like to be in elementary school.

His latest book, “The Losers Club,” is about a boy who gets in trouble for reading too much in school – when he’s supposed to be doing math or listening to teachers. While Clements was not exactly like that in school, he has vivid memories of being singled out for being bookish.

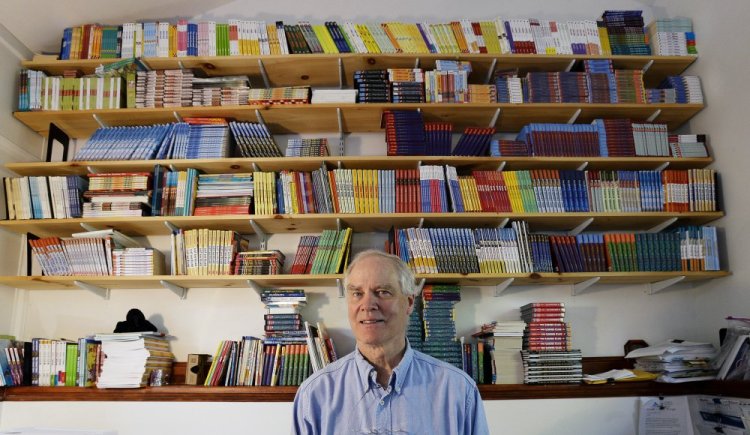

“I heard some girls on the bus one day, I think I was in the fifth grade, saying so-and-so’s having a party and do you think Andy’s going to come,” said Clements, 68, sitting in his home office. “And the other girl says ‘Who? Him? He’s such a bookworm.’ I remember that so vividly.”

Clements has written more than 80 picture books and middle-grade novels during the past 30 years and has made a national reputation for himself writing for children about what children know best: school, teachers and the daily dramas surrounding both.

His first school-based novel aimed at a middle-grade audience (roughly ages 8 to 12) was “Frindle” in 1996, about a boy who invents a new word for pen and watches it become wildly popular. The book was a best-seller and has sold more than 6 million copies

A New York Times reviewer, writing about “The Losers Club” when it came out in August, called “Frindle” a classic and said Clements’ most recent book could not match it. But the reviewer praised “The Losers Club” for the “low-key geniality common to all his work” and said “it gives fried bookworms everywhere the satisfaction of knowing that friends may desert them (if only temporarily), but books never will.”

Clements’s geniality in writing about school kids stems from his view that school is not merely a child’s preparation for the rest of his or her life.

“Kids don’t go to school simply to get ready for life. They go to school to actually live their lives right now,” said Clements. “I’ve come to understand that childhood itself is a constant. Times and technology change, but the process of growing up, of moving from home to school, of having your first run-in with an authority figure other than your parents, doesn’t. If I can connect with that real sense of what childhood is, then my characters are going to feel real.”

A BOYHOOD OF BOOKS

A signed book to Andrew Clements from his parents from Christmas 1959. Staff photo by Shawn Patrick Ouellette

Clements grew up mostly in New Jersey and Illinois, in a family with six children and hundreds of books. He remembers his parents reading to all their children, and that books were prized. Books were what they got for presents. On a shelf near his writing desk, he keeps the copy of the 1908 children’s novel “The Wind in the Willows” he got for a Christmas present more than 60 years ago. An inscription inside reads “To Andrew Clements: Christmas 1959: With love from Mother & Dad.”

Clements describes his childhood as “comfortably middle-class” with a father who worked in the insurance business and a mother who took care of six children. His family had spent summers in Maine for years, and as a child, Clements spent summers in the western Maine town of Hiram. About 10 years ago, Clements and his wife, Becky, bought their own Maine vacation home on Hancock Pond in Denmark. Three years ago they decided to move to Maine year-round after living more than 25 years in Westborough, Massachusetts. They bought a hilltop home, dating to 1890, in West Baldwin, west of Sebago Lake.

Though he read a lot as a youngster, Clements didn’t give any serious thought to becoming a writer until he was a high school senior and a teacher gave him an A on a poem. She also wrote that the poem was “so funny” and ought to be published.

While in college, he taught a summer writing program to high schoolers and found he liked it. He graduated from Northwestern University near Chicago and then got a master’s degree in teaching from National Louis University, based in Chicago.

He taught for seven years, in fourth grade, eighth grade and high school. But he was let go a couple times because of declining enrollments and decided to try something else. He ended up in publishing, first writing captions for a how-to book on craft projects, then in sales with a company that imported children’s books from Europe.

It was there he began writing picture books, working with illustrators, around 1985. In 1990, he went to an elementary school in Middletown, Rhode Island, to talk about his picture book, “Big Al,” about a scary-looking fish who had trouble making friends. He was talking to a group of first- and second-graders about word origins and about how words mean what we decide they mean. The kids didn’t believe him so he took out a pen and explained that if everybody started calling a pen a … “frindle” (a word he made up on the spot), then it would be a frindle. The kids all laughed, and Clements had the idea for his first middle-grade novel, “Frindle,” which came out in 1996.

Clements’s latest book, “The Losers Club.” Photo courtesy of Random House Children’s Books

GETTING THE DETAILS RIGHT

“The Losers Club” is about a sixth-grader named Alec who is so enamored of reading he does little else. When he gets a book for a birthday present, he reads it immediately while his party goes on without him. He’s been told not to read in school, unless that’s the assignment. He figures that’s OK, because he’s starting a new after-school program and assumes he’ll be able read there while the other kids play games.

But the rule at after-care is you have to be involved in an activity or a club, though you can start your own club with one other person. When he spies a girl quietly reading, he enlists her for a reading club and calls it “The Losers Club,” hoping it will curtail others from joining.

“I know kids like that. I think everybody knows somebody like that, typically somebody who is called a bookworm and teased about it,” Clements said.

Clements feels it’s important to make the details of childhood real in his book, which means the details of everything a child might do.

For his series “Benjamin Pratt & The Keepers of the School,” Clements immersed himself in sailing and sailing terminology, as Benjamin lives in a seaport town, and he and his dad both sail. Clements had sticky notes on each arm of his chair marked “port” and “starboard,” so he could visualize being in a ship as he wrote.

He’s currently working on a book involving buttons. It’s about a girl whose grandfather is rehabbing an old Massachusetts mill building, and she’s allowed to take whatever she wants out of it. As the mill had once made clothing, she found buttons – boxes and boxes of antique buttons.

Clements immerses himself in whatever he happens to be writing about. His next book is about a girl who becomes fascinated with buttons, so he made it his mission to learn everything he could about them.

So, on a table near Clements’s writing desk on a recent Tuesday were four plastic bins full of antique buttons he got from a Cornish antiques dealer. Clements wants to know as much about buttons, if not more, than his characters do. He can pick out an 1850s cow bone button, as well as ones made of glass, celluloid, Lucite and Bakelite.

Clements’s button-collecting girl becomes fascinated and focused on her new hobby, and Clements has a history of doing that himself. He got a D in penmanship once – he still has the report card because his mother saved it – and he decided he wanted to improve. He began practicing and later took courses in calligraphy. He got so good that one of his four sons asked Clements to write the invitations to his wedding. In his home office, he keeps a dozen or more calligraphy pens handy.

Sometimes when he speaks to school groups, Clements, bring his report card to show that you can always improve yourself. And you can always learn, even when you’re done with school.

“I always tell young writers, become an expert, no matter what you’re writing about. The more you know, the more convincingly you can write,” said Clements. “If you start digging into anything, you discover there’s a lot going on.”

Ray Routhier can be contacted at 210-1183 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Twitter: @RayRouthier

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story