AUGUSTA — The air was stuffy in the Danforth Gallery on Thursday evening, as dozens of Vietnam-era veterans and their family members browsed an exhibit of canvases and bunks that once filled a naval transportation ship.

That ship, the U.S.N.S. General Nelson M. Walker, transported American soldiers and Marines to the Vietnam war between 1966 and 1967, carrying up to 5,000 troops at a time.

The exhibit included an actual berthing unit from the troopship, with eight canvas bucks attached to a metal frame and old orange lifejackets hanging from either end.

But the stuffiness in the gallery, which is at the University of Maine at Augusta, didn’t compare to the claustrophobia and heat experienced by the men who actually slept in those bunks, said John Lambert of Alfred, who sailed on the General Nelson in July 1966.

As an infantryman in the Vietnam War, Lambert, 70, helped patrol the country’s central highlands and the Cambodian border. But on his initial, three-week cruise across the Pacific Ocean, he felt anxious about what awaited him, and the cramped environment didn’t help.

“It brings back a lot of memories,” Lambert said of the exhibit. “It was extremely hot in the middle of July, and there were 5,000 men on the ship, so it was very crowded. … We also had small duffel bags that we had to fit in our bunks, and we had rifles that we had to sleep with, and there was no air.”

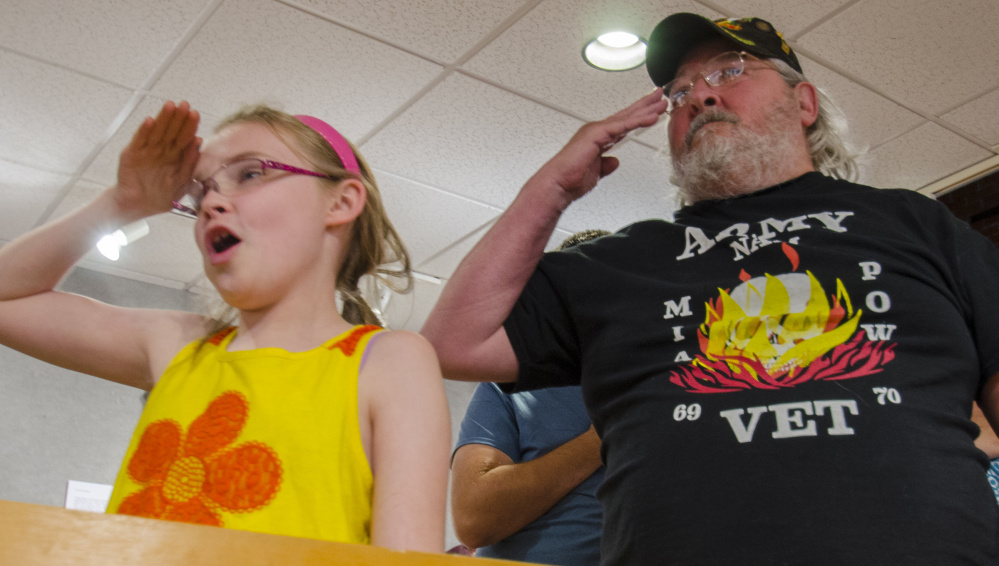

Lambert was one of about 40 veterans who was honored Thursday night at a ceremony put on by the University of Maine at Augusta and the Maine Bureau of Veterans’ Services.

For the last month, the berthing unit from the troopship has been displayed alongside other artifacts from the war preserved and compiled into an exhibit called the Vietnam Graffiti Project by Art Beltrone, a military artifact historian.

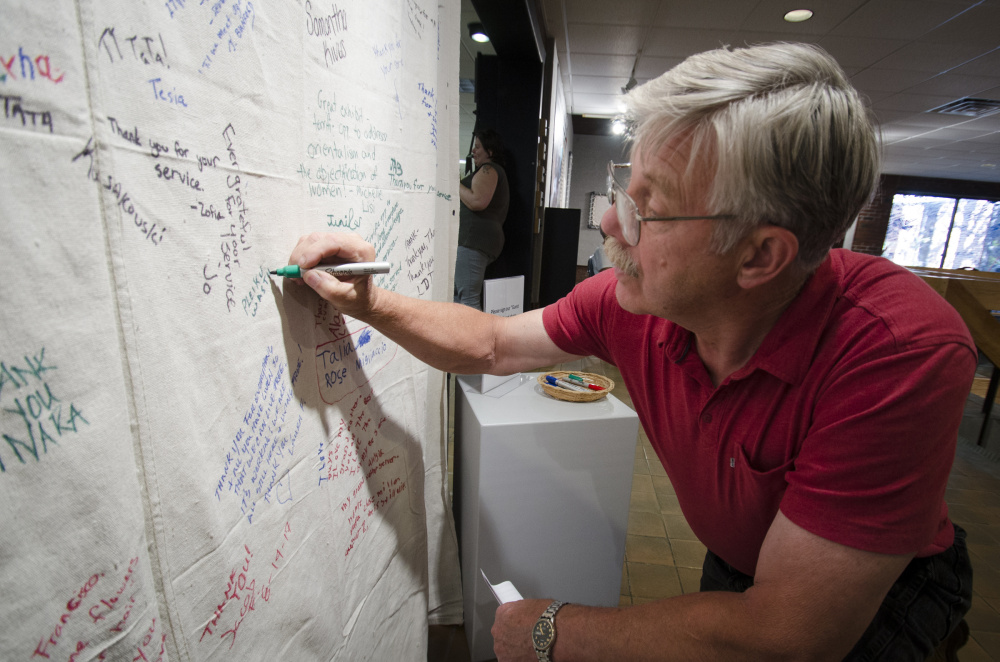

The canvases from other bunks were stretched across the walls of the gallery, providing a clear view of the graffiti that troops had scrawled in black ink.

Some wrote their names, nicknames, ranks and dates of service. They also drew caricatured portraits of the women they met or imagined in foreign countries, with titles like “Sharon Lee: Queen of the South Seas” and “Miss Okinawa ’67.” Other pieces suggested the fever dreams that the troops, possibly seasick, experienced on their way to war, such as a reptilian rodent with its fangs bared, or a fish with a muscular arm sticking out of its body.

The exhibit came to Maine as part of an initiative by former President Barack Obama to honor veterans who served during the Vietnam War, roughly coinciding with the 50-year anniversary of America’s entry into the long conflict.

Of the more than 100,000 veterans living in Maine, about 45,000 served in Vietnam, said Adria Horn, director of the state Bureau of Veterans’ Services. But according to Horn, many of them were not recognized for their service.

Horn, a U.S. Army veteran herself, served in Iraq and Afghanistan and said that Vietnam veterans have been some of the biggest supporters of soldiers coming home from those contemporary wars.

But after Vietnam, they “didn’t get the proper recognition,” she said. “To be spit on, to be ashamed to wear a uniform, they struggled so my generation didn’t have to. … You didn’t get the welcome home you deserved.”

Horn presented pins, certificates and commemorative coins to the Vietnam veterans who were present.

“It’s been a long time coming,” said one of the veterans, Fernando Paradis of Waterville, immediately after Horn had presented the items. “I want to say: greatly, greatly appreciate it, on behalf of all of us. Thank you.”

Two other men at the ceremony had also sailed on the General Walker. One of them, Al Sabaka of Bridgton, has met the historian who made the exhibit and helped bring it to Maine.

The other, Hank Deshane, 73, also recalled the claustrophobia he felt while on the ship in Oct. 1967, but described himself as relatively lucky. Unlike other soldiers, he had a bottom bunk, meaning he could roll onto the cooler tile floor when the quarters got too hot. And his berth was high enough in the ship that it had a porthole, so he could glimpse outside.

During the war, Deshane helped maintain the Chinook helicopters used by the U.S. Army, but on the three-month cruise from Oakland, California, none of the U.S. troops knew what to expect.

“We didn’t even know where we were going,” he said.

Ironically, perhaps, it was the well-informed, English-language broadcasts of Hanoi Hannah, a Vietnamese radio personality, that informed the men where their units were headed.

“It was saying, ‘Welcome to Vietnam. We’re waiting for you,'” Deshane recalled of her show, which the troops picked up on their own radios. While her intelligence turned out to be correct, he continued, “We all laughed at it, because we knew it was propaganda.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story