In the race to sustainability, a small college in central Maine is proving tough competition.

Unity College won the grand prize for sustainability in July at the National Association of College and University Food Services conference in Nashville, Tennessee, beating out finalists Duke University and the University of Texas at Austin, among others.

That success is partly a result of a unique strategic move that places dining services under the sustainability office.

“Everybody’s got to eat, so we are using that common meeting place, so to speak, a common table, to really reflect the sustainable values and mission of the campus,” said Jennifer deHart, chief sustainability officer at the college of about 700 students.

The National Association of College and University Food Services gives the Sustainability Awards to schools that show “outstanding leadership in the promotion and implementation of environmental sustainability.” The association supports the triple bottom line approach that Unity College also uses, which measures success not only through finances but also environmental impact and social responsibility. It’s often called “people, planet, profit.”

The association hands out gold, silver or bronze prizes to its members in five categories related to sustainability, and those that win gold compete for the grand prize. Unity College, which diverts nearly half of its waste from landfills, won gold in the waste management category, followed by Oregon State University and Georgia State University.

When Unity won the grand prize, “it was a complete shock,” deHart said.

Jennifer deHart, left, chief sustainability officer at Unity College, and Lorey Duprey, middle, director of dining, accept the grand prize for sustainability from a representative of the National Association of College and University Food Services at the group’s conference in July in Nashville, Tennessee.

“We were kind of a David in David and Goliath in this scenario,” she said, as Unity is small compared to many of the other winning schools.

DeHart’s position was created in the 2015-2016 school year to ensure that all areas of campus life aligned with the sustainability goals of the school that brands itself “America’s environmental college.”

Unity has a number of goals and commitments, ranging from a push toward carbon neutrality to ensuring the college has infrastructure in place to withstand the changing climate, deHart said.

Another goal is reducing the school’s waste.

Unity produces about 160 tons of trash each year. About 48 percent is diverted: Organic waste, 23 percent, goes to Exeter Agri-Energy to be turned into energy for a farm; and recycling, 25 percent, goes to a center in Norridgewock. The school uses the Crossroads Landfill in Norridgewock for the trash it can’t send anywhere else.

The average residential college student wastes about 142 pounds of food per year, according to RecyclingWorks, a recycling assistance program in Massachusetts. Another group, known as APPA: Leadership in Educational Facilities, found that a full-time student creates a median 363 pounds of trash each year, according to deHart.

The school has about 485 students on meal plans and about 140 staff members who use the dining hall, as well as a few thousand visitors each year for tours who get free meals, deHart said.

In the winter of 2015, dining was moved from the business office to the sustainability office in an effort to improve waste management efforts and the environmental quality of the food the college buys.

DeHart said the collaboration made sense because of the “wide-ranging impacts” dining can have, from the food system to student health.

“It may be different, but it’s effective … in allowing dining to be a leader on campus in sustainability,” she said.

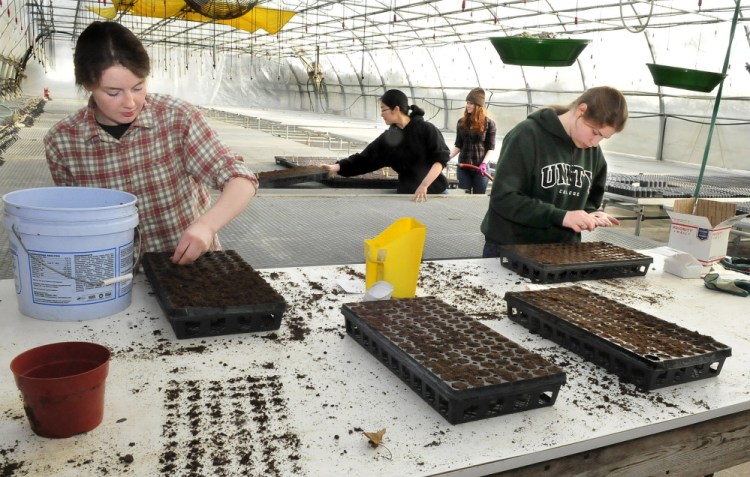

After the merge, dining began to work with the McKay Farm and Research Center in Thorndike, an extension of the campus also housed under the sustainability office that’s used for both educational and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Over the past school year, the college’s dining services used more than 3,600 pounds of produce from the farm, which doesn’t include the amount of produce it converted into things such as condiments and herbed salts. The percentage of produce that comes from the farm compared to the total used to feed dining patrons was not immediately available.

While the school isn’t saving much money using the farm, it isn’t losing any money either, deHart said. McKay Farm has stayed “price competitive” with other small local farms, so it wasn’t fiscally difficult to make the change.

Looking ahead, deHart said she hopes dining services will get more food from the farm in the future.

“One of our limitations is the time and storage capacity to process food while it’s in season to be available at different times of year,” she said, which might involve additional infrastructure such as freezers and cold storage.

That also could be a learning opportunity, she added. Students or volunteers could learn about how to preserve food, and the reliance on a local farm could force students to realize the seasonality of food.

The school also negotiated a new contract with Performance Food Group, its largest food service distributor, after the merge.

Performance Food Group has an automated reporting system that tracks purchases by category, so the college is working with them to track which food purchases fall within the guidelines for the Real Food Challenge, which provides definitions for food that is local, fair trade, ecological or humane.

Unity was manually tracking the amount of purchased food that fell within that category before starting to collaborate on an automated process, deHart said, which was difficult and time consuming. The college estimated that 10 percent to 15 percent of its food purchases fell within one of the Real Food Challenge categories.

One of deHart’s goals is to get to 20 percent or more.

“Those four elements are significant factors in the food system that … support and promote good behavior and sourcing in those categories” as opposed to ignoring practices in the food system, she said. “We’re choosing to support the better choices.”

The school plans to continue working with its distributors and others, deHart said, hopefully exploring ways to get “more local food in the environment.”

It’s also working with FINE, or Farm to Institution New England, which is a six-state nonprofit network working to increase the amount of local food served in schools, hospitals and colleges, among other places.

“Anytime schools can work together or with these smaller suppliers, … that creates networks and networks create more market stability in terms of what can be provided and buying power,” deHart said.

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story