WAYNE — There’s a difference between the walls that Steve and Molly Saunders are trying to build in Mexico, and the one President Donald Trump has in mind for that same country’s border.

Trump’s wall would attempt to keep people out of the U.S. — the “bad hombres” who would enter this country illegally, as he has said.

The Saunders hope that their walls will, once joined by a roof, become home for a family they met on a recent trip to the Yucatan Peninsula.

They’re raising money for that family to build a solid house, a project that’s meant to restore the goodwill with our southern neighbors that they think the Trump administration has eroded.

Engaging with Latin America is nothing new for the Saunders, who are both in their early 70s and own Wayne Village Pottery. They’ve been traveling south of border ever since they went to El Salvador as Peace Corps volunteers in the late 1960s. Steve used to teach Spanish in the Maranacook Area Schools, and after Molly was exposed to pottery in Mexico, it became her lifeblood.

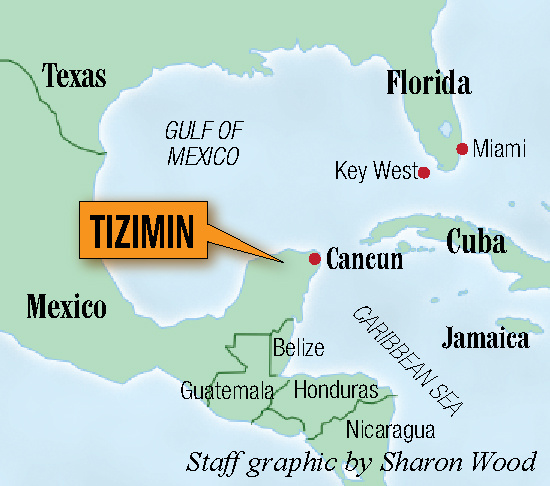

So when the couple was looking to leave town last winter, they chose an inexpensive area east of Cancun, not expecting the chain of events that would, in a couple weeks, pair them with a local family trying to improve its precarious living situation.

At one point on their trip, the Saunders planned to visit Tizimin, a city of about 50,000 people, to watch a local baseball game.

Before reaching the city, they read in a newspaper about Antonia Dzul, a restaurant worker who lived in Tizimin and had unsuccessfully applied for government assistance to replace the leaky, tar-paper roof on her home. According to the article, Dzul lived in the rickety home with her parents and two children.

That article piqued the Saunders’ interest, and when they traveled to Tizimin, they stumbled upon the office of the newspaper that had written it. Soon, a reporter was bringing them to meet Dzul.

“I was expecting to give her a few bucks and leave,” Steve Saunders recalled. “I said, ‘I want to give you a new roof,’ and I gave them some money … $100 that I had in extra cash, which is a lot of money for them.”

By the next day, however, the newspaper had published an article suggesting the Americans had loftier goals: to help Dzul build an entirely new home.

The article included a large photo of the Saunders visiting the Mexican family in their bare, dirt-floor home. Daylight shone through holes in the ceiling, and a hammock hung to one side. A headline above the article roughly translated as, “Help has arrived for family.”

In fact, by the time Saunders read that article, they were coming around to the idea themselves.

Giving away money didn’t come naturally to them. As Peace Corps volunteers, they’d learned about the importance of sustainable, community development.

But they asked Dzul to get an estimate for a new home, and the lowest offer came in at $4,000. The Saunders thought they could raise at least that much, so long as Dzul opened a bank account to which they could wire the money in $1,000 installments. They also asked her to send photos showing that construction was progressing.

“By that point, we had gotten to know the family, so we felt comfortable,” Steve Saunders said.

Since returning to Maine, the Saunders have already raised $2,000 for the family. The family has sent photos documenting the cinder block foundation they’ve already built, as well as the walls that are now underway.

The Saunders hope to raise another $6,000 on a GoFundMe page they’ve created, to cover the rest of the building costs and have enough for some of the family’s other expenses.

The Saunders were moved to help Antonia Dzul and her family for a couple reasons. One was simply their material need.

According to the Saunders, Dzul felt she was denied government assistance for a new roof because of her support for a political party that wasn’t in power.

Dzul spent all her wages on food and an education for her 14-year-old daughter, Karen, but worried she wouldn’t be able to afford the next semester, Steve Saunders said. Dzul’s father, Antonio, gathered firewood for about $3 per day, but her mother, Flor, didn’t have the capital to pursue business opportunities she’d been considering, like selling hot dogs by tricycle.

Unlike many in Mexico, Dzul also didn’t have relatives working in the U.S. who could send money home, Steve Saunders said.

The Saunders also felt the need to forge positive, lasting relationships with people in Mexico, to counteract what they see as the harmful rhetoric and policies of President Trump. Besides proposing to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, Trump denigrated Mexican citizens during his campaign.

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said, in the speech announcing his candidacy for president. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

The Saunders couldn’t feel more differently. During their travels, Molly Saunders said, they’ve found Mexicans to be “very welcoming and hospitable.” And they’ve spoken with Mexicans who don’t think a wall will keep their countrymen from entering the U.S.

“‘It’s about building houses, not walls,'” Steve Saunders said of their project, recalling something that a family friend recently told him.

He continued, “We’ve traveled so much there, and interacted with so many people in different parts of Mexico. It’s unfair for the Trump administration to be talking only in terms of building walls.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story