AUGUSTA — Julie Lanoie said her grandmother was a simple housewife in Amsterdam. She was shy and never did anything without her husband, Philip Peper. In some ways, she couldn’t survive without him.

But during World War II, it was Philip Peper who couldn’t survive without his wife. He was Jewish, and during the Dutch Resistance, his wife, Allegonda Balte-Peper, hid him and about 45 other Jews in their home in the Netherlands.

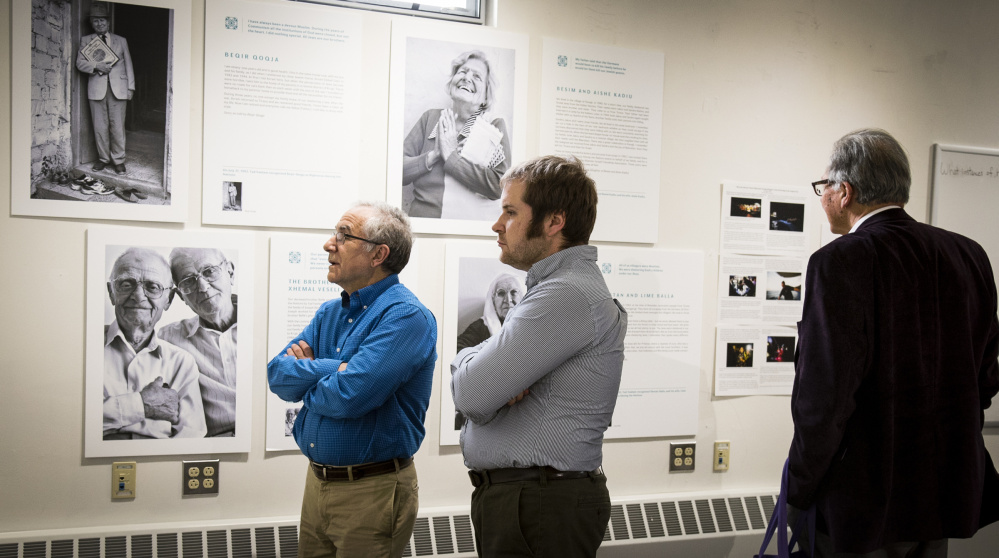

Julie Lanoie, a nurse from New Hampshire, spoke about her grandmother to an audience during the opening night program about the new “Heroism in Unjust Times: Rescuers During the Holocaust” exhibit at the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine on the University of Maine at Augusta campus.

Lanoie was emotional as she spoke about her grandparents and spending time with them in a camping trailer in New Hampshire. She talked about how her grandmother’s home in The Hague was used as a temporary home for people protected during the resistance.

She said her grandmother, like so many people who experienced the Holocaust, didn’t talk about what she lived through while hiding dozens of Jews, including her husband, but her grandfather wouldn’t stop talking about it.

“She avoided the topic and didn’t appreciate being questioned, but he didn’t want anyone to forget,” Lanoie said. “He wanted us to know he owed his life to her.”

Philip Peper would tell an 8-year-old Lanoie about people being rounded up and loaded into boxcars, among other images not exactly common for a young child to hear about. Lanoie’s grandmother avoided the topic and didn’t appreciate being questioned about it, while her grandfather didn’t want anyone to forget what happened.

“He talked a lot about it, with lots of facts and no emotion, and he wanted to make sure I understood it,” Julie Lanoie said. “It was the way he was wired, but he was probably not capable of feeling those emotions until his late years.”

Her mother and Balte-Peper’s daughter, Joan, came to the United States in 1957 and said she grew up knowing her mother went through something traumatic during the Holocaust, but she didn’t know the details.

“The first time I ever had what I’d consider an anxiety attack was when my husband and I saw “Sophie’s Choice” in the movies,” Joan Lanoie said. “When the trains came, I had a hard time, and I do still.”

Balte-Peper spent the last several years of her life in Florida, and Julie Lanoie said she lived with her during her grandmother’s final months. She told the guests in attendance Wednesday that one night her grandmother awoke screaming that there were bodies all around her while gunshots were going off.

“She was asking for help, begging for help and when she woke up, she said she wished she had done more,” her granddaughter said. “I told her she did her best, which is all anyone could ever do.”

Julie Lanoie said families of Holocaust survivors often are haunted by feelings of gratitude and guilt, and those differing emotions are challenging to live with.

“We ask ourselves about if others had lived instead of us, what would those people have become?” she said. “I always think about whether I’d have made the same choices as my grandmother did if I was in her same situation.”

Elizabeth Helitzer, the Holocaust center’s executive director, said people mostly think about the end of the Holocaust and not of the resistance and all the heroic stories of people throughout the horrific act.

“I thought about ordinary people being put through extraordinary circumstances and rising to the occasion,” she said. “I also thought about how important inspiration and hope is, and we need to hear these stories because of what’s happening nationally.”

Author Walt Bannon told the story of his grandfather, August Felix Florin, and his mother, Andree, who were a part of the Belgian Resistance. Andree Florin, at age 14, was forced to live in her basement for four years during the Nazi occupation of Belgium. His mother struggled to survive while her father did all he could to help whomever he could.

Bannon said that while growing up, he always thought of his mother as someone who had survived World War II, but he didn’t know anything else about what she experienced. It wasn’t until she broke her hip a few years ago and had to stay with her son in Maine that she began to tell her life story.

“We never really knew what and just accepted that she was just a girl who survived,” Bannon said. “She started reverting back to things she did during the war, like not eating.”

He said his mother wouldn’t eat and would say she learned during the war to say she was never hungry “because then (the Nazis) couldn’t make us hungry” when she didn’t have any food.

“I wanted to cry because I could see her going back … 70 years and she was experiencing it all over again,” Bannon said. “It was heartbreaking, but I knew there was a story, and I had to get to it.”

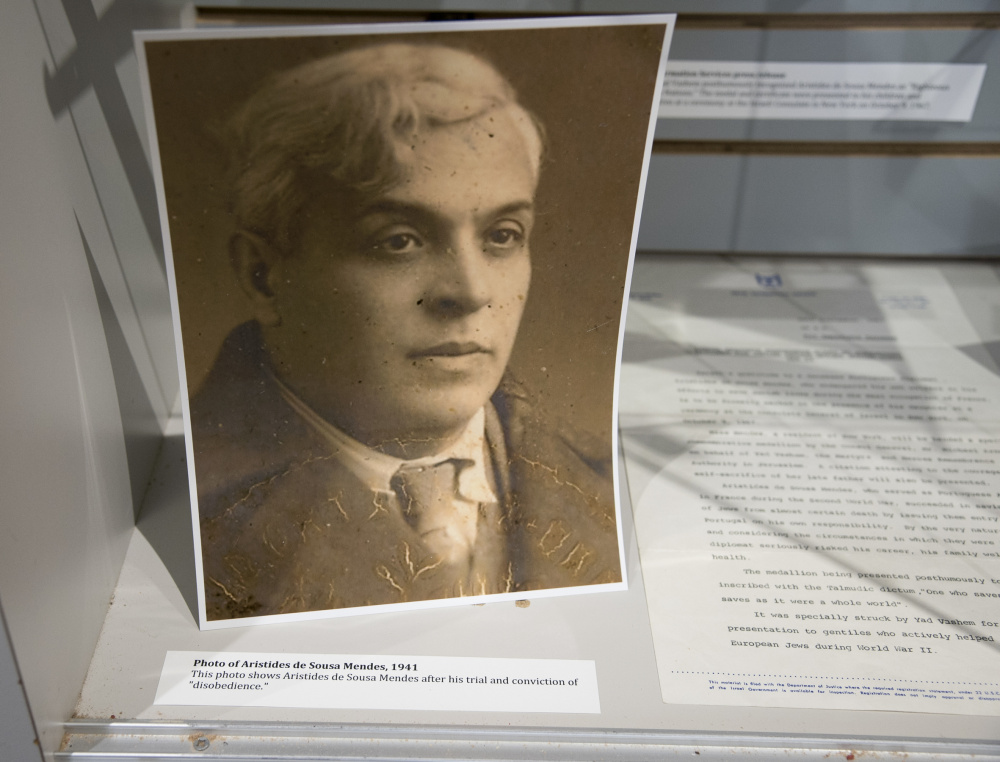

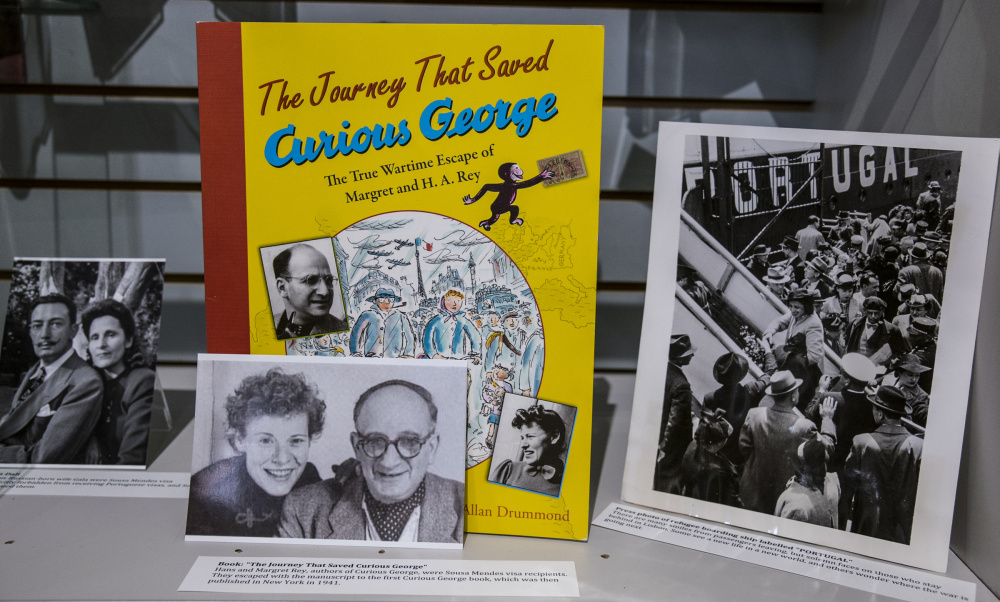

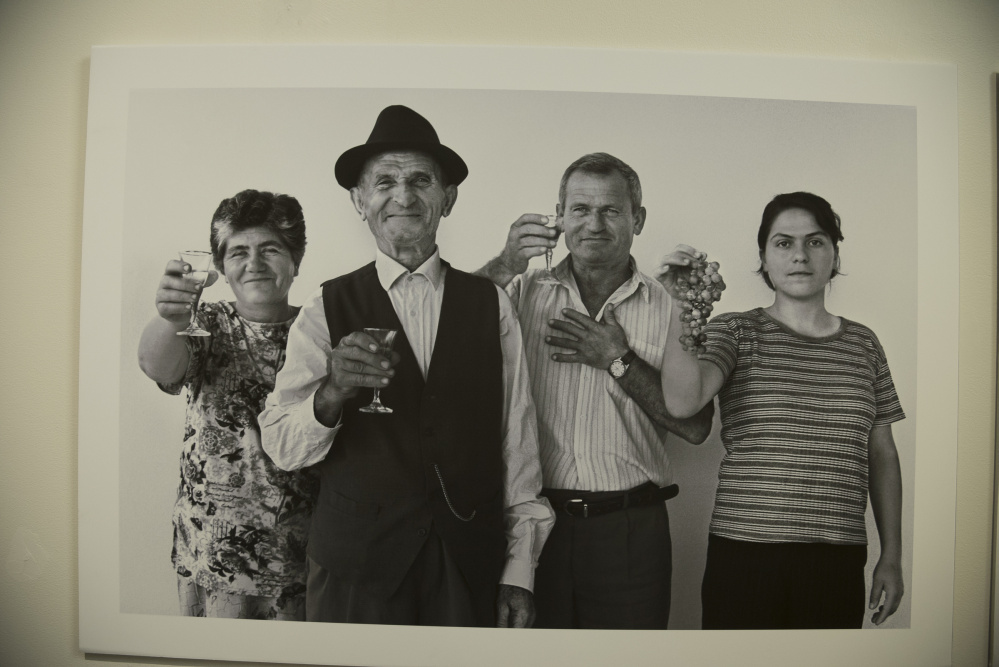

The Holocaust and Human Rights Center exhibit, which will be open until Aug. 11, features artifacts and stories from rescuers including Balte-Peper, Florin and perhaps the most well-known rescuer, Oskar Schindler, subject of the 1993 movie “Schindler’s List.”

Jason Pafundi — 621-5663

Twitter: @jasonpafundiKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story