Sheri Piers of Falmouth was the fastest woman from Maine in last year’s Boston Marathon, so it may have been hard for her teenage daughter to comprehend a time when women were barred from competing in races much longer than a mile.

Piers, 45, recently showed 13-year-old Karley a sequence of black-and-white photos from the 1967 Boston Marathon – in an era when only men were allowed entry.

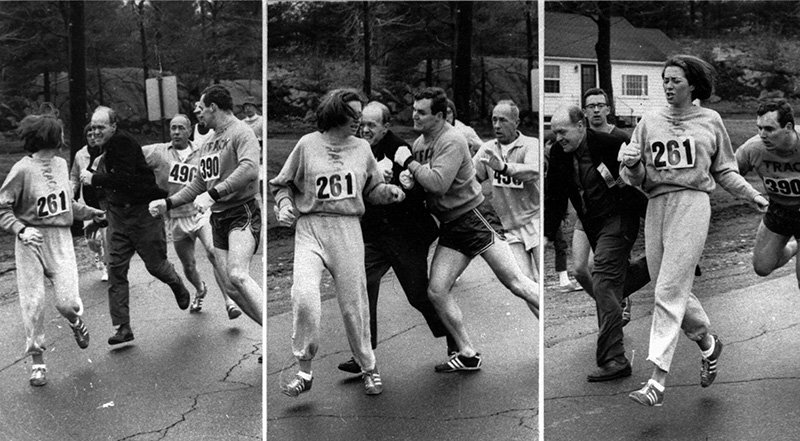

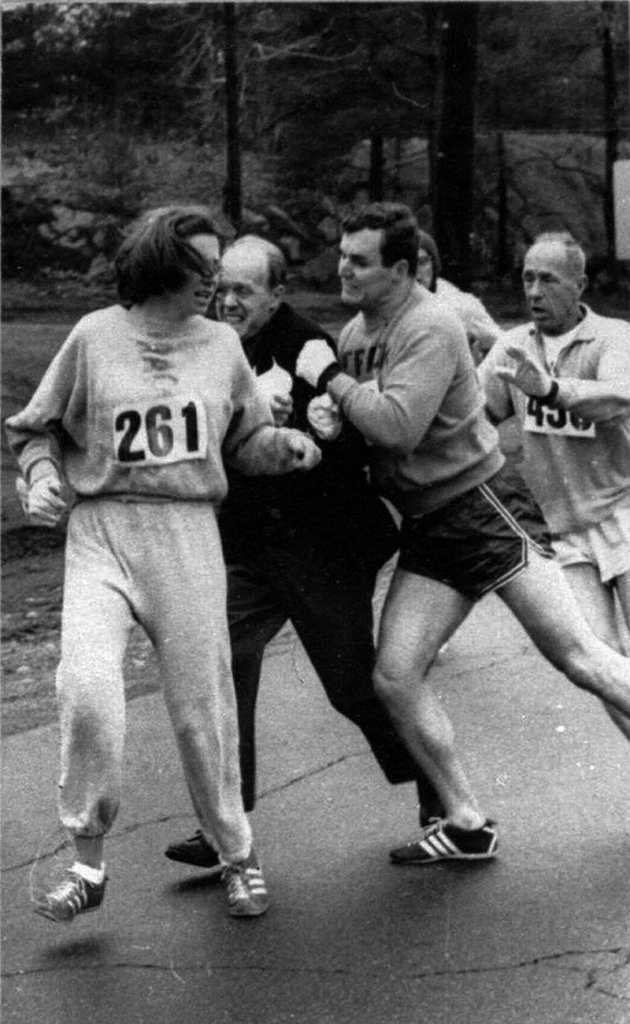

The first shows an angry race official attempting to rip the bib number (261) off a woman running in a baggy gray sweat suit. The final frame shows the woman’s boyfriend, a collegiate hammer thrower, crashing his shoulder into the official, allowing her to remain on the 26.2-mile course.

The woman, a 20-year-old college student named Kathrine Switzer, had gained entry to the marathon only because she had listed her name as “K.V. Switzer” on the application and officials assumed she was a man. She recovered from the race official’s attack – 2 miles into the race – and her humiliation turned into anger and resolve.

Despite painful blisters, Switzer persisted and became the first woman to officially finish the Boston Marathon. Her time was four hours and 20 minutes.

“It’s amazing to see those pictures,” Sheri Piers said. “How anyone could even think that’s OK to do these days, being pushed off a course and trying to rip off her number? I can’t imagine watching that happen.”

Switzer, now 70, will be back in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, on Monday to celebrate the 50th anniversary of a run made historic because of those iconic photos, which elevated her unwanted incident into a cause for equal rights. In this year’s marathon field, men still outnumber women (16,432 to 13,714) but more runners under age 40 are women (7,143) than men (5,936).

Switzer is running the marathon in support of 261 Fearless, a nonprofit foundation to empower women around the world through a social running community. More than 100 women (and six men) from 20 countries will run with her in support.

“What was a dramatic incident 50 years ago became instead a defining moment for me and women runners,” Switzer said in announcing her return to Boston. “The result is nothing less than a global social revolution; there are now more women runners in the United States than men (females accounted for 57 percent of those who completed U.S. running events in 2015, according to data from Running USA).

“These women are both fearless and compassionate, wanting to help other women around the world achieve their goals. Because of this team’s great fundraising, 261 Fearless will be able to spread our message far and wide.”

Seana Roubinek of Rockport is running for Switzer’s foundation and has raised $14,300 for the cause.

“I’ve been involved with charity teams before,” said Roubinek, 49, a computer analyst who is battling a recurrence of ovarian cancer. “I’ve admired Kathrine Switzer for a long time, since I heard her speak at my first 10K back in ’99 at Dallas. I didn’t even know how I was going to finish a 10K, but she basically said whatever you want to do, you can do it. Your body will do what your mind tells it to do.”

Before the 1967 marathon, Switzer had been training at Syracuse University with the men’s cross country team and a coach named Arnie Briggs who had run Boston 15 times. In her memoir, “Marathon Woman,” Switzer wrote that only after she completed a 31-mile training run with Briggs was he convinced that she should enter Boston. He also said it would be wrong to enter without registering.

“We checked the rule book and entry form; there was nothing about gender in the marathon,” she wrote. “I filled in my (Amateur Athletics Union) number, plunked down $3 cash as entry fee, signed as I always sign my name, ‘K.V. Switzer,’ and went to the university infirmary to get a fitness certificate.”

‘FIRST GAL TO RUN MARATHON’

A year earlier, Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb had sneaked onto the course near the start and run the full course in 3:21:40. She had wanted to avoid race officials who denied her application. At the time, AAU sanctioned the race, and its rules prohibited women from racing longer than 1.5 miles.

The next day, Boston’s Record American put two photos of her on its front page beneath the headline: “Hub Bride First Gal to Run Marathon.”

Gibb was also the first female finisher in 1967 (3:27:16) and 1968 (3:30) but wasn’t recognized as the women’s champion until 1996 as part of Boston’s centennial celebration. On Monday, for the second year in a row, she will serve as the race’s Grand Marshal, along with 1967 men’s winner Dave McKenzie.

Despite the notoriety achieved by both Switzer and Gibb, Boston didn’t formally admit women into its field until 1972, and then only if they could achieve the men’s qualifying standard of 3:30. Still, Boston was the first major marathon to allow women. A year later, on the starting line of the 1973 Boston Marathon, the race official who had attacked Switzer gave her a kiss. She and Jock Semple had become friends.

Switzer’s best time at Boston came in 1975, when she finished second among women in 2:51:37. She won the 1974 New York City Marathon, but her biggest contribution to the sport may have been as one of the prime movers behind a global series of running events for women. The Avon International Running Circuit included 400 races in 27 countries for over 1 million women and helped pave the way for the inaugural Olympic women’s marathon in the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

“Kathrine was not the first woman to win Boston,” said the winner of that first Olympic marathon, Joan Benoit Samuelson of Freeport, “but because of the strength of those photos, Kathrine has had the opportunity to do a lot for women in sport and women in distance running.”

‘THERE OUGHT TO BE A PLAQUE’

Samuelson and Switzer both ran the Cherry Blossom 10-Miler earlier this month in Washington, D.C., and each won their age group, the 59-year-old Samuelson in 1:03.55 and Switzer in 1:30:31.

“I see her at most major marathon events,” Samuelson said of Switzer, who often provides television commentary. “The pictures continue to be shown and I think people are still learning about how far women have come, not only in sport but in society over the years. There have been different watershed moments that have stuck in people’s minds and illustrate that it hasn’t always been easy.

“Kathrine’s continued involvement and legacy in the sport have benefited and inspired the generations of women and girls who run.”

Gary Allen, a longtime Boston Marathon participant from Great Cranberry Island, ran his first marathon in 1977 and his first Boston in 1979, the same year a Bowdoin College senior named Joan Benoit set an American record in her Boston debut.

“I was in high school when the whole Title IX thing happened,” Allen said of the 1972 federal civil rights law that prohibits sex discrimination in education. “Prior to that, girls didn’t play sports equally with boys. There was no such thing as girls running cross country.”

Except, perhaps, at Mount Desert Island High, where Allen’s coach Howie Richard welcomed girls.

“There were a lot of coaches in Maine,” Allen said, “who were not happy with him.”

Allen said the Boston Marathon has a long and storied history and the incident between Switzer and Semple is one of the most important and symbolic. He wanted to know exactly where it happened, so he consulted with Tom Derderian, who wrote a history of the race that was published in 2014.

“You can see in the photograph a rocky outcropping to the right side of the road, and you can still see the same rocky outcropping today,” Allen said. “Honestly, there ought to be a plaque put there on that spot. I think it’s wonderful that she’s going back to celebrate her 50th anniversary.”

The historic incident, captured in grainy black-and-white photos, continues to resonate today.

“Once you see that image, you can’t forget it,” said Scarborough’s Kristin Barry, 43, the fastest woman from Maine in the 2015 Boston Marathon. “It’s so jarring and hard to comprehend at this point. My (16-year-old) daughter has trouble believing that women weren’t allowed to run because from the time she was very young, playing soccer and running and whatever activity she wants to participate in, there were never any barriers or obstacles.”

She paused.

“It’s remarkable how things have changed,” she said, “and how quickly they changed. I remember my mom telling me when she was in high school there was cheerleading, and that was it for girls. You couldn’t do any other sports.”

Glenn Jordan can be contacted at 791-6425 or at:

Twitter: GlennJordanPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story