Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

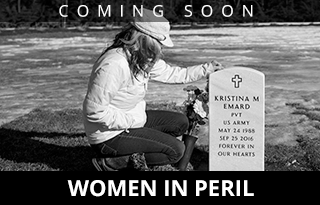

Sam Stevens’ drug tragedy began when he tried marijuana at a friend’s birthday party in sixth grade, back when he still played Little League baseball. It ended a year ago when the 23-year-old took a fatal dose of fentanyl-laced heroin while sitting in his father’s Volvo in a Machias parking lot. Sam had returned home from a residential treatment program in Florida to attend the birth of his son, but he died two weeks before Lucca was born.

His funeral drew so many people that they couldn’t all fit inside Machias Christian Fellowship Church, so many stood outside the no-frills building and listened to his service as it was broadcast outside on a makeshift sound system. Sam didn’t attend the church, but his father invited Paul Trovarello, a man known for counseling drug users, to handle the funeral because he didn’t want to cover up his son’s addiction.

“Sammy was more than just the addiction, so much more, just the funniest, sweetest boy, and such a good athlete, but heroin killed him, and I’m not going to try to hide it,” Jeff Stevens said. “We spent too many years around these parts trying to hide this kind of thing, but people need to understand that it can get to anybody, this heroin. It can take people away, little by little, right before your eyes, until they’re all gone.”

Stevens tells his son’s story while sitting in the screen porch of a house overlooking the Whiting side of Gardner Lake, nursing a coffee mug of liquor that he often slips away to refill. Between shift work at a nearby telecommunications center and the grief over his son’s death, Stevens said everyday is a struggle, especially on days when Sam’s stepmother, Wanda, is away with her own sons.

All three of Stevens’ boys went into lobstering, and all three were at one time heroin addicts, Stevens said. He doesn’t know if the oldest one is using now because they don’t talk. He said he knows his middle son was still using after Sam died, and he suspects they might have been together when Sam overdosed, or at least shortly before. But they aren’t talking anymore either, both still angry over Sam’s death.

Sam Stevens played on state championship soccer and basketball teams at Washington Academy. By age 23 he was dead from an overdose of fentanyl, heroin and Valium. Photo courtesy of the Stevens family

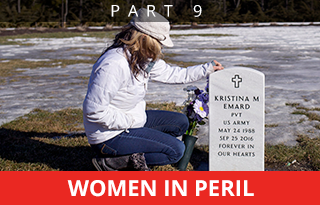

From the porch, Stevens can see the spot where Sam is buried, out on the point where he loved to fish. Sam’s dog likes to sit by the grave. In the summer and the early fall, Stevens would take Lucca out there, sit under the tall pines and tell him stories about his dad – how he played on two sports teams that won state champion Gold Balls for Washington Academy, how a slight lisp made him shy, how he loved to quote lines from his favorite Austin Powers movie.

Trovarello said Sam’s death shook the community. His was one of the first public heroin funerals in the area, with the cause of death – acute accidental intoxication of the combined effects of morphine, fentanyl and diazepam, otherwise known as a heroin overdose – listed in the death notice and obituary and the circumstances discussed openly at the service. Sam’s boyish good looks, the memories people had of him on the Gold Ball teams and his mild-mannered demeanor had won him many friends, even during his long struggle with heroin.

“I’d say his death, and the way it was handled, it was a turning point,” Trovarello said. “If it could happen to him, it could happen to anyone.”

By the time he died, most people who knew Sam were aware he was addicted to heroin. He never tried to hide it, his stepmother said. He had been expelled from Washington Academy in his senior year for supplying another student with cocaine. He’d stolen checks from his father’s checkbook to cash for drug money. Before going to rehab, he had tried to clean up at home, and his father had even tried to help by buying him black-market Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid dependency. But nothing stuck.

His lobster boat captain, Peter Barton, said he knew Sam had a drug problem, but a friend who had once hired Sam as a deckhand said he was a hard worker and kept his drugs off the boat, so Barton brought him on in 2014 as his second man. His job would be to take turns banding lobsters and baiting and stacking traps.

Sam was funny and charming while they talked about girls, ice fishing and hunting. Only once in two years did Sam show up too high to haul. He got a warning, but that was it. The only other time that his addiction came up was after Barton found out Sam had gone to rehab.

It would be Sam’s last attempt at recovery. He left for the Florida rehab center at the end of the 2015 fishing season.

Barton said he reached out with a few encouraging Facebook messages. They had planned to catch up when he came home, but Sam died two days after he returned to Maine.

“I didn’t know how bad it was, I guess, but then again, we never really talked about it,” Barton said.

“He kept it off the boat, and it didn’t hurt his work. I can’t control someone’s personal life. I run my business separate from my personal life. I am not going to fire someone just because they’re addicted, but if they’re bad for business, they’re gone. Sam, he was good for business.”

Penelope Overton can be contacted at:

poverton@pressherald.com

Twitter: PLOvertonPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story