Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

Sixth of 10 parts.

BETHEL — For nearly eight months, as her daughter grew inside her, Shannon Long was free of opioids.

The pregnancy had flipped a switch and she committed to bettering herself. She tapered and then eliminated her drug use. She passed her GED test and completed training to be a certified nursing assistant. She looked ahead to life as a new mother.

But drugs were still all around her. Even in the quiet mountains of western Maine, she couldn’t escape them. Her boyfriend, the father of her unborn child, had helped her quit using but wasn’t ready to give it up himself.

And the emotional pain that led Shannon to use in the first place hadn’t disappeared.

At first, she just did a little. A small line of a crushed-up pill. She immediately regretted it.

Two weeks later, though, Shannon used again. And again. And then pretty much every day until her daughter was born in May 2012.

In the hospital, she promised herself she’d stay clean, if not for herself, then for her baby, whom she named Hope, after her great-grandmother.

“I thought I had every reason to stay sober – and I did,” she said, her voice barely a whisper. “But it wasn’t enough.”

Today, Shannon, 24, is more than six months clean. She’s honest about her recovery – an up-and-down journey that has consumed the last several years of her life and is, by her own accounting, far from over.

When people battle addiction, there is treatment – the generally short-term, medication-assisted method or stays in a residential facility or counseling – and there is recovery, which is entirely individualistic. Recovery is often a lifelong process and the path rarely moves along a straight line. Most drug users don’t simply realize they have a problem, seek help and get clean; it’s a constant struggle. Along the way, there are often missteps and relapses and failed attempts.

Charles Pattavina, the chief of emergency medicine at St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor and president of the Maine Medical Association, said few people grasp how difficult recovery can be. Or how easy it is to get hooked in the first place.

“I think what strikes me most is this idea that a lot of these people have a fairly benign story as to how they became addicted,” he said. “I think before we think ill of someone who is addicted, we need to consider that they aren’t that different from the rest of us.”

One of the major difficulties with opioid addiction is the risk of relapse, which the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates at 40 percent to 60 percent. That means for every five people in recovery, two or three of them will likely use again.

Shannon knows her sobriety isn’t guaranteed. She is enrolled in a program that combines Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid dependence, with regular counseling. She supplements that with group meetings with other people in recovery and tries to go at least once a week. She spends most of her time with Hope, who is now almost 5.

This is the first time in her recovery that she has taken a hard look at why she started using to begin with. It’s been difficult at times, but that is true for many who battle addiction, especially people like Shannon, who haven’t had the easiest of lives.

‘I DON’T KNOW WHAT I WAS THINKING’

Shannon grew up in Massachusetts, in a chaotic home.

“I have vivid memories of going to parties with my parents or having people at the house,” she said. “Crawling on the lap of some guy my mom brought home. Finding my dad passed out drunk in the bathtub. Getting picked up by my grandfather at the police station after my parents were arrested at a party.”

Her parents eventually split, and Shannon moved to Maine to live with an aunt, in a household where there were rules. After a couple of years her mother moved to Maine and asked Shannon to move back in. She did, and before long the partying started again.

One day Shannon and a friend decided to check out the medicine cabinet. Her mother had a bottle of Klonopin – a benzodiazepine used to treat anxiety. Shannon moved on to prescription painkillers, Vicodin and OxyContin.

She met a guy who had easy access to pills. She didn’t want to deal with the things going on in her life and pills helped her to forget.

From then on she started using almost every day. It wasn’t until she got pregnant at 18 that she realized she had become dependent.

“We were living in a moldy camper in my boyfriend’s parents’ backyard; I don’t know what I was thinking,” she said.

When Shannon brought her daughter home from the hospital, drugs were everywhere in the community, including the heroin that all the users were raving about. She resisted it, but after eight days she broke down and tried it.

To understand how a mother could use heroin with her infant child in the next room is to understand the power of opioid addiction.

“Just thinking about it makes me shake my head in such disappointment and shame. There are just so many things that I have done over the years that make my heart so heavy,” she said.

By the time Hope was 6 months old, Shannon stopped breast-feeding over fears she might do her daughter long-lasting harm.

After several months of heavy use, Shannon and her boyfriend tried to stop. They bought Suboxone on the street, hoping that the medication, used to treat opioid dependence, would help them get clean. But they always ended up on heroin again.

That’s how the cycle went for a couple of years.

“We would try and last a few days at most. Most of the time it was all talk,” she said.

The above timeline shows how Shannon Long, like most people addicted to heroin or other opioids, relapsed into drug use several times but then fought to get clean again as part of her ongoing recovery effort.

Eric Haram, former behavioral health director of the Addiction Resource Center at Midcoast Hospital in Brunswick and now a treatment consultant, said the up-and-down nature of recovery is one of the hardest things to bear in mind about battling addiction. Worse still, with each relapse a person often falls to lower depths, to newfound levels of rock bottom.

“Addiction is a window-of-opportunity illness,” Haram said. “You need to reach them when they come to you. Otherwise, you risk losing them.”

BREAKING DOWN, ASKING FOR HELP

After a while, Shannon was using only Suboxone and was getting it legally. For 18 months, she thought she had it managed.

But in January 2016, she relapsed after her boyfriend got into a car accident that killed the mother of one of her friends.

Worse still, he had relapsed and kept it from her. Already on probation over previous drug charges, he went to jail and still faces manslaughter charges from the accident. Shannon was alone.

“I let the wrong person into my life,” she said. “I was lonely, I wanted attention. He was high and that’s all it took for me.”

Her drug use escalated. The next few months were the most destructive and reckless of her life.

She overdosed in March and woke up soaking wet in a bathtub. A few weeks later, she overdosed again. This time paramedics came.

“I remember waking up and there were all these people around and I said, ‘What did you people do to me?’ ” Shannon recalled. “And somebody said, ‘We just saved your life.’ ”

But she kept using. One day she sat in her car parked outside Crocker Pond in Bethel, looking out at the water.

FROM THE EDITOR

COMING SATURDAY: Community in crisis: Battle against opioids rages in beaten-down Sanford

“I remember visualizing a button and thinking if I could just press it and make all this go away,” she said. “In that moment, I was so fed up about chasing the drug. I wasn’t happy anymore. It wasn’t numbing anything.”

Days later, she broke down and asked for help. Her family said they would care for Hope and help pay for Shannon’s treatment.

The key to long-term recovery is building skills to cope with life that don’t involve masking it with a substance. It’s far easier with a support system, but often people have alienated family and friends by the time they reach that point.

Ann Dorney, a Skowhegan physician who treats addiction patients, said many of them are dealing with more than addiction. They are dealing with depression or anxiety or worse and those issues linger even after the drugs are taken away.

Shannon said she had never learned those coping skills.

In June of last year, she went to Massachusetts and New Hampshire for treatment, then came back to Maine in August. She and her family went on a hiking and camping trip in the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

“That was a big deal for me because I was giving up my weekend to get high,” she said.

Shannon got through that weekend, and then the next few. She hasn’t used heroin since.

Shannon Long tries to get something out of her daughter Hope’s eye at their home in Bethel. Long, a single mother, has been in recovery from substance abuse since September. Photo by Brianna Soukup

CREATING A NEW LIFE WITHOUT DRUGS

Experts say the gap between people who understand addiction and those who do not is wide, and it stands in the way of a comprehensive public health strategy.

“Different people come to addiction in different ways. We want to assign some blame to them,” said Pattavina, the Bangor emergency physician. “People clearly understand it’s a problem, but I think we need more understanding.”

Shannon has been keeping two journals throughout her recovery: one for herself, the other for Hope. She doesn’t share everything with her young daughter now, but someday she wants her to understand the struggle and doesn’t want to forget anything, even the bad.

On a weekday in late January, Shannon arrived at her counseling office in Norway. The counselor declined to be identified but allowed a reporter to sit in.

They started talking about a plan for her to stop taking Suboxone, and about her boyfriend’s pending trial for manslaughter.

With her sobriety, Shannon said she feels like she’s progressing and leaving him behind. But she worries about breaking up her family, too.

“Just because you’re together doesn’t mean you’re a family,” the counselor said.

Recovery isn’t just eliminating drugs from one’s life. It’s creating a new life without them.

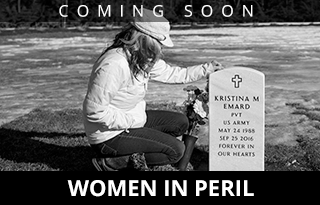

VITAL SIGNS: Deaths from prescription painkiller overdoses among women increased more than 400 percent between 1999 and 2013, compared to 265 percent among men, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

A couple of weeks later, Shannon stood before a group of about 400 students packed inside the cafeteria at Spruce Mountain High School in Jay. Matt Baker, a sergeant with the Oxford County Sheriff’s Office who had gotten to know Shannon, asked her if she’d come with him to speak to some high school students.

She was nervous, but she told her story. As she tried to put into words the grip that heroin had on her life, Shannon shared this, about an almost benign trip to pick up her daughter from child care.

She and her boyfriend were already high when they picked Hope up, but they stopped to do more heroin before driving back home.

Behind the wheel, Shannon nodded off and the car went over a snowbank, landing on its roof and sliding along. Her daughter was in the back seat.

“And the sickest thing is: While we’re upside-down in this vehicle, we crawl out,” Shannon said. “Our daughter is hanging upside-down, not a peep. I pull her out of the car and the very next words out of my mouth were, ‘Where’s the dope?’ I was more concerned about where our drugs were than anything. And it didn’t stop us. I almost killed our daughter and that wasn’t even enough to stop me, because that’s what it does, that’s what it does to you.”

After the assembly ended, most students left quickly.

Some stuck around, though, to introduce themselves to her and the others who spoke. They shook hands and said thank you.

A girl approached Shannon and asked if she could have a hug.

Shannon smiled and leaned in.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story