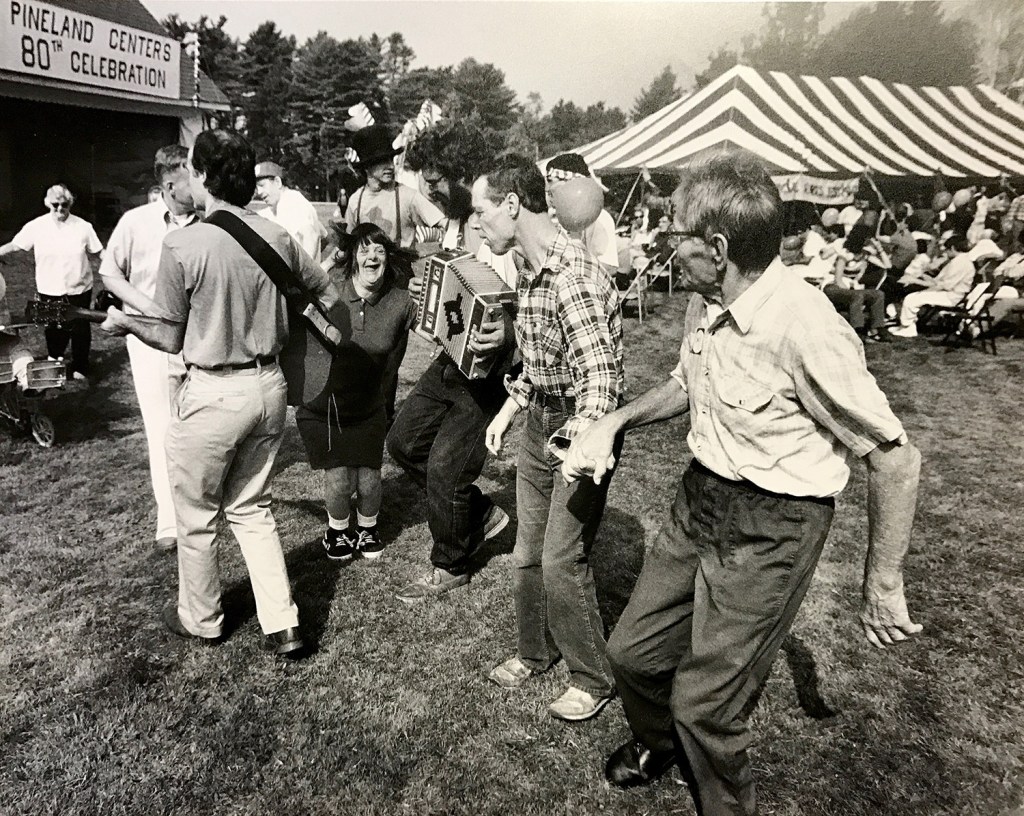

When Pineland Center closed in April 1996, advocates and state officials considered it a major victory for adults with intellectual disabilities. Maine emerged as a national leader in how to provide quality care for this population in community group homes, rather than large institutions.

On closing day, pigeons were released to symbolize freedom, and everyone who had ever lived at the New Gloucester center was invited back for a barbecue to celebrate its permanent shutdown.

But in the past several years, Maine has been turning the clock back on these adult services, advocates say, leaving thousands of adults with autism, brain damage, Down syndrome, and other intellectual developmental disorders vulnerable. Leaders of nonprofits say the system of community-based services is on the verge of collapse.

But a Maine Department of Health and Human Services spokeswoman disputed the characterization of a failing system, saying Maine is one of the best states in the country for these services.

However, waiting lists for services have swelled over the past eight years, while MaineCare reimbursements have been repeatedly scaled back, drastically reducing payments to the nonprofit organizations that run group homes. The trends are related, advocates say, with the cuts making it increasingly difficult for families to obtain services under Section 21, the portion of the MaineCare code that governs services for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Currently, about 1,200 developmentally challenged adults are on a waiting list – or about one of every four to five people who qualify for the service, according to state statistics. That’s a tenfold increase since 2008, when the waiting list stood at 111. The population of adults who qualify for the services has slowly increased, and there are now about 10 percent more adults who qualify for Section 21 than 10 years ago, advocates say.

Now the LePage administration is proposing changes in the formula for calculating reimbursement rates that would reduce payments to service organizations even further – by as much as 7.5 percent. Group home operators say that will jeopardize their financial solvency, and many are likely to close. As financial pressures mount, the ones that are left would be a shell of their former operations, and the state would be in danger of warehousing clients in group homes, they say.

“We are at the point where we are going to be creating mini-institutions, mini-Pinelands, all over the state,” said Ray Nagel, executive director of the Independence Association, a Brunswick nonprofit that operates group homes.

But DHHS spokeswoman Samantha Edwards disputes the idea that rate cuts contribute to increased waiting lists.

“To our knowledge, no one has gone without services due to an unwillingness on the part of providers to provide the care at the current rates,” Edwards said.

But nonprofit leaders say the system doesn’t have enough capacity to serve its clients.

Ryan Dufour, 18, who has high-functioning autism, lived in transitional housing for several weeks this summer after he graduated from high school – without any structure or programs – and he said it was terrible and stressful.

“We are not a thing that can be put into a box,” Dufour said in an interview at his grandmother’s mobile home in Freeport.

Ryan Dufour, 18, who is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, was cut off from services as soon as he graduated from high school in June. Now living with family members in Durham and Freeport, he is on a long waiting list for community-based services, while trends in Maine make those services tougher to find. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Dufour’s situation is typical of the challenges adults with intellectual disabilities face in trying to navigate the system, experts say. He lives now with his great-grandfather in Durham, and has been on the waiting list for Section 21 group home services since June – a wait that could extend for a year or longer.

The state and federal governments have devised more generous benefits for children – including extensive programs in schools and group homes with activities, therapy and community-inclusion programs.

“On June 16, he graduated from high school and was enjoying full 24-hour services,” said his grandmother, Leslie Sullivan, who raised Dufour. “By June 18, it was all gone. He was left with nothing. His world changed immediately.”

CUTS HAVE BEEN BIPARTISAN

The reimbursement rate cuts for community services have been bipartisan – occurring under the Democratic administration of Gov. John Baldacci, and under current Republican Gov. Paul LePage.

As the cuts have taken effect, the wait list has expanded from about 110 in 2008 to 1,200 currently, according to state statistics.

Advocates say the state could end up backsliding to a time when adults with intellectual disabilities received little or no services and were vulnerable to abuse.

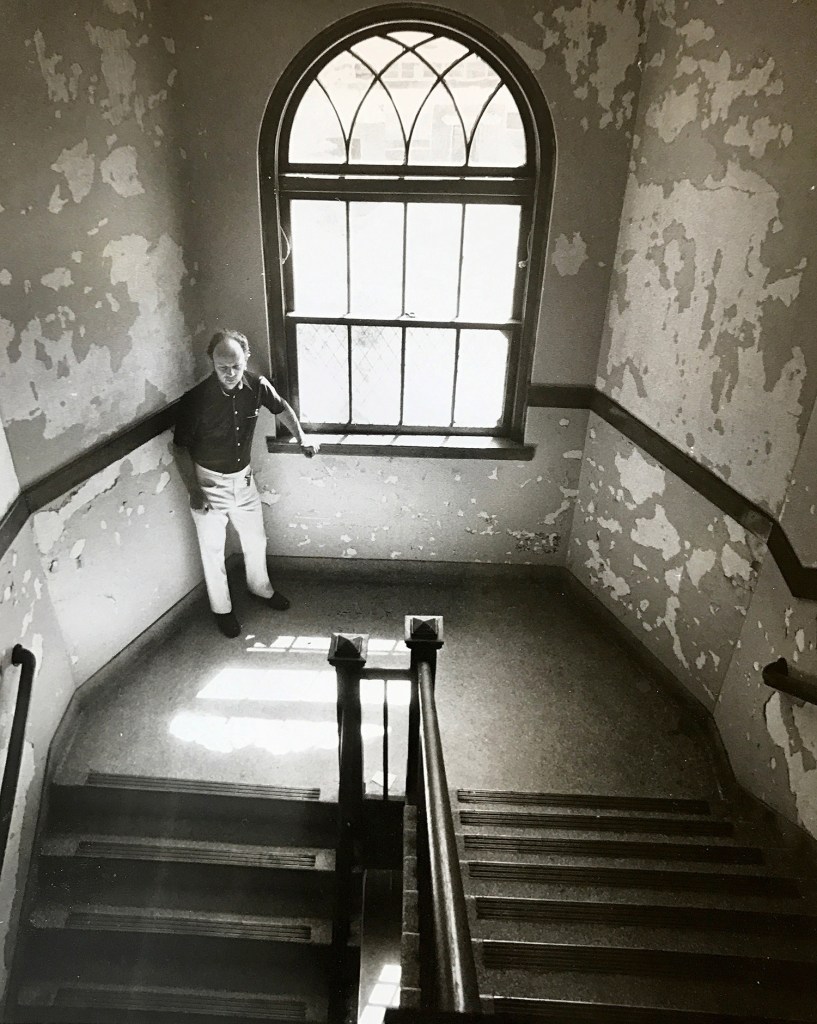

Pineland had been notorious for abuse, especially through the 1970s – including forced sterilizations, removing healthy teeth from young people to prevent biting, unnecessary drugging of patients, unsanitary conditions and frequent use of straitjackets and chair restraints.

“For showers, people were lined up and sprayed with a garden hose,” said Roger Deshaies, a former Pineland employee and Maine Department of Health and Human Services executive who lobbied for decades for Pineland to close. Deshaies said it was common for people to just stand around naked, and the staff was indifferent or overwhelmed to the conditions of the people in their care.

“There was no attempt to improve their lives or functioning,” Deshaies said. “It became a passion of mine to try to change things. Rather than running away from it, we wanted to try to do something about it.”

Deshaies said the system improved and the worst abuses were alleviated by the 1990s, but it became impossible to justify keeping Pineland open when many clients were receiving much better care in the community. By the early 1990s, the state decided to close Pineland, and it took two years to transfer the remaining 300 or so clients to community care. At its peak in the 1950s, Pineland had about 1,500 clients.

From the 1980s and through the 2000s, the state’s system for adults with intellectual disabilities was also being monitored by a court-ordered consent decree after families filed a lawsuit against the state. Under the consent decree, a court-appointed official supervised the system to make sure patients were being cared for, an important check on the system to prevent backsliding. The consent decree expired in 2010, after the state agreed to pass a law that said adults with intellectual disabilities were entitled to substantive services.

Those laws are now largely being ignored, advocates say.

REIMBURSEMENT RATES DECLINE

Nonprofit agencies said the system for the most part worked well from the late 1990s through the late 2000s, with group home providers reimbursed at a fair rate that allowed them to offer substantive services to adults with intellectual disabilities, or ID.

“Maine was a state to look up to,” said David Braddock, a professor at the University of Colorado who researches state-by-state trends for state services for adults with disabilities.

Deshaies said for the first several years the state negotiated separate contracts with each group home provider, and then he was contracted to create a standard rate for DHHS in the mid-2000s that he said was considered “fair and equitable.” Deshaies said he had already moved to Arizona by then but helped the state come up with a formula that worked for the nonprofits, wasn’t overly generous with taxpayer money and provided good services for clients.

But within a year after the formula was implemented in 2007 the reimbursement rates were already under attack by the state.

During the past eight years – spanning the Baldacci and LePage administrations – reimbursement rates for the nonprofits that provide the services for adults with ID have been cut substantially, a systemic whittling away of what once was a proud component of Maine’s social services safety net. Cutbacks in real dollars have slashed the reimbursement rate by 12 percent since 2008. When factoring in inflation, the cuts represent a 31 percent reduction, the nonprofits say.

A pending change in the funding formula equivalent to an additional 5 percent to 7.5 percent cut will be another major blow to the system – causing closures and a reduction in services at the group homes, advocates say.

On top of that, the state has cut room and board reimbursements for group homes by 60 percent, from $6 million in 2006 to $2.1 million currently, said Todd Goodwin, CEO of Community Partners, a Biddeford nonprofit. Also over the past 10 years, the state has imposed a number of unfunded mandates and requirements on the group homes, increasing operating costs while at the same time cutting rates, advocates say. MaineCare – the state name for Medicaid, which is funded by a blend of federal and state dollars – spends between $275 million and $350 million per year on Home & Community Based Services – which includes group homes, in-home services and programs in the community – for adults with intellectual disabilities.

“It’s a big crisis,” said Peter Kowalski, president of John F. Murphy Homes in Auburn. “If these cuts happen, we will be reimbursed less than what it costs to operate a home.”

GROUP HOMES AS MINI-INSTITUTIONS

One in four to five adults with ID who qualify are now on a waiting list, and some clients are told to expect to wait years.

Meanwhile, the group homes that remain would be in danger of not providing adequate services, leaders of nonprofits say.

The group homes that don’t close would more resemble a “warehouse” for patients, rather than comprehensive services to help them improve – such as therapy, day programs and staff to help them integrate into the community, hygiene and social programs.

The institutions that some state officials and advocates tried so hard to move away from would in essence be coming back with group homes that offer few services, mini-institutions spread out all over the state, Nagel said.

Maine is bucking a national trend by defunding its group homes, according to a statistical analysis by the University of Colorado. States are now more likely to invest in community services like group homes when compared to three years ago.

“These are very negative steps that Maine is taking,” Braddock said. “All of Maine’s trends are going in the wrong direction.”

Maine was one of the first states to completely eliminate institutions for adults with intellectual disabilities, and there are still only 13 states that have done so.

But Edwards said reimbursements for services under both Section 21 and Section 29 have increased from $278 million in 2011 to $350 million in 2016. The number of adults served has increased from 4,128 in 4,882 in that time frame.

The analysis by the University of Colorado shows the opposite, that Medicaid spending on these services declined 20 percent from 2009 to 2015.

Section 29 is a related but separate Medicaid program that provides in-home or day program services for adults with intellectual disabilities, but those services are far less comprehensive than the 24-hour, seven-day services available under Section 21. The Section 29 services are typically about 10-20 hours per week, according to the nonprofit agencies.

Edwards also pointed out that LePage attempted to budget $46 million to reduce the waiting lists for adults with intellectual disabilities, but was rebuffed by the Legislature.

But Goodwin said that point is a “giant smokescreen” because without adequate reimbursement rates, the system cannot absorb additional clients. If the reimbursement cutbacks go through, he said, it would instead further reduce the system’s capacity to serve developmentally challenged adults.

“We’re having a really hard time serving the clients that we have now,” Goodwin said.

The reimbursement cuts and unfunded mandates have also compounded hiring and turnover problems at the nonprofits, they say.

Pete Plummer, chief operations officer at Woodfords Family Services in Portland, said it’s a coin flip when they hire an employee whether that person stays even a year on the job. The program can only afford to pay $9 to $10 an hour as a starting wage, or it will start losing money on its group homes. The jobs combine demanding work with low pay, which leads to high turnover.

“People can make more money working at McDonald’s than they can working for us in the group homes,” Plummer said.

Plummer said the constant staff turnover is a strain on clients, who are often just starting to get comfortable with the employee who’s caring for them when the worker changes jobs, and they have to adapt to someone new. The clients have disabilities that make structure important and change more difficult.

“It’s really terrible care for these clients,” Plummer said.

Goodwin, at Community Partners in Biddeford and also president of the Maine Association for Community Service Providers, said his agency and all of the others he’s talked to have similar employee retention problems.

Nagel said it’s getting to the point where they have to consider staffing at low levels to keep places operating. But then the clients aren’t being cared for.

“We could end up with just a complete bare-bones service, but it’s not really helping them very much,” Nagel said.

Kelsey Dunn, left, a residential services manager for a group home in Topsham, helps Kate Riordan communicate with an iPad. Riordan, 42, has cerebral palsy. She is a 15-year resident of the home. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Goodwin said it bothers him to see so many people suffering and the state doesn’t seem to have any empathy for clients on a long waiting list. Instead, it wants to cut more.

“There is zero recognition of the cost of doing business for a very needy population,” Goodwin said. “The capacity in the system is dwindling. If these cuts go through, this will very likely be the proverbial straw.”

Edwards said the proposed rate change is not a cutback, but a “realignment of policy to articulate that each provider must provide 100 percent of the services they are reimbursed for. This seems like a no-brainer, but an antiquated Medicaid policy allows providers to bill for 100 percent of a service, but only provide 92.5 percent of that service.”

Goodwin said while it’s true nonprofits can bill for 100 percent while providing 92.5 percent of services, the formula was designed to allow for flexibility, for times when clients need extra help and a home is being staffed at above 100 percent. The state does not reimburse group homes for staffing that goes beyond 100 percent.

He said the nonprofits don’t mind a simpler system, but rates must be increased to adjust for the losses they would be taking if the formula is changed without a hike in rates.

Goodwin said part of the reason they’ve been cut so many times is the meager clout that they have in Augusta.

“We’re easy targets representing a group of people who are easily marginalized,” Goodwin said.

At a group home in Topsham, Kelsey Dunn works long hours for low pay while managing two group homes. She said it’s always a struggle finding employees who will stay. She is committed to the job partly because she has a 21-year-old brother, Silas, who is autistic and just recently transitioned into a group home, although not the one she works at.

“I could make more money at other jobs,” Dunn said.

She said if people like her didn’t work in the system, it would be even more difficult to find employees.

‘HE NEEDS HIS OWN LIFE’

Sullivan, the grandmother of Dufour, who is on the waiting list for Section 21 services, said the family tried to secure adult services a few months before he graduated from high school, but instead he was put on a waiting list. He lived in transitional housing before moving in with his great-grandfather.

Dufour was attending a high school in Ellsworth located on the KidsPeace campus, where he also lived in a supported group home. Sullivan, who raised Dufour, said he thrived in that structured setting. He was on the honor roll and he took advanced science and math classes – coursework with the same rigor as non-developmentally challenged students – and with the right direction could have a great career, she said.

Ryan Dufour, who has autism spectrum disorder, holds one of many records in his collection while his grandmother Leslie Sullivan – who raised him – looks on. Dufour was cut off of services as soon as he graduated from high school in June and is now on a lengthy waiting list. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

“Ryan is extremely smart. He could be a rocket scientist,” Sullivan said, beaming. But Dufour “needs help regulating his emotions,” Sullivan said, and he requires a structured day to succeed. Sullivan said Dufour has not lived with her since he graduated because she’s worried about him becoming violent when he gets frustrated, especially considering she is also raising Dufour’s 8-year-old sister.

Dufour is currently living with a 72-year-old great-grandfather but spends a lot of time at Sullivan’s mobile home in Freeport.

“He shouldn’t be hanging out with us all the time. He needs his own life,” Sullivan said.

Dufour said he realizes he needs to live in a group home setting to help him reach his goals – which include going to college and having a family.

“About this Section 21 business. I have been waiting since June for permanent housing for myself,” Dufour said. “I think that’s too long to wait, to be honest. No one should have to wait that long. It would help straighten me out. It would help me find a place to start.”

Dufour said just because he needs help doesn’t mean he or others with intellectual disabilities should be marginalized.

“There is no reason at all to live in shame,” said Dufour, a fan of “The Lord of the Rings,” the explorer Leif Ericson, the Beatles, and singer Wayne Newton.

Sullivan said her grandson – “my hero, my heart and soul” – should be given a chance to thrive. And she said she worries what would happen to people with more severe disabilities than Dufour and with less family support.

“The state can expect more homeless people and the shelters filling up,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story