Mental health and juvenile justice experts say the state of Maine had an obligation to continue a regimen of mental health treatment for a transgender teenager after he arrived at Long Creek Youth Development Center.

Charles Maisie Knowles, 16, was incarcerated at the South Portland facility in August on a charge of arson and later hanged himself with a bedsheet after going on and off suicide watch multiple times. His mother, Michelle Knowles, said Long Creek doctors were focusing on her son’s “day to day” issues and denied him more regular, in-depth mental health treatment for weeks following his incarceration until she and an outside doctor intervened.

Officials who oversee the state-run Long Creek have refused to answer any questions since Knowles’ death Nov. 1. But juvenile justice policy experts and a clinician interviewed by the Maine Sunday Telegram say that if the mother’s contentions are accurate, then the practices at the state’s premier juvenile correctional facility fly in the face of national standards and professional best practices accepted around the country.

“Every red flag should have gone up for them when this kid entered their facility,” said Dr. Andrea Weisman, who oversaw all health services for detained youth in Washington, D.C., for five years until 2011. “The care that he received was woefully inadequate. He came in with an alarming charge. He had a known psychiatric history. He was likely on psychotropic medication. He had a known history of suicide attempts. And he was a known transgender. That should have set off an immediate red flag. They did not protect him. They did not provide him adequate services.”

But precisely what types of mental health care were administered, and how frequently, and whether care began promptly after Knowles was locked up are questions the state Department of Corrections has so far refused to answer.

Facing dual investigations by both the office of Attorney General Janet Mills and his own department, Corrections Commissioner Joseph Fitzpatrick has remained silent following multiple requests for interviews and the repeated submission of more than two dozen detailed questions by the Sunday Telegram about Knowles’ care and how Long Creek staff responded to pleas by Michelle Knowles for help. Corrections officials have refused to answer even basic questions about Long Creek or disclose how many juveniles are detained there.

Sen. Stan Gerzofsky, D-Brunswick, a member of the Legislature’s Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee, said that although the full committee has not been briefed on the matter, he has been in touch with people intimately familiar with the situation. Gerzofsky said he is not surprised by the lack of public statements by officials.

He expects the initial Department of Corrections investigation to take several weeks, but the attorney general’s investigation could take longer.

“It’s not just the liability issue,” Gerzofsky said. “People are in our custody, and we’re responsible for their care. Did we drop the ball or not? I’m not seeing any signs that we dropped the ball, but I don’t have all of the facts in front of me.”

‘NOT A MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT FACILITY’

But in interviews last week, national-level policymakers and clinicians have said that no matter what, the state has an obligation to identify and treat mental health needs as soon as someone is taken into state custody.

Those standards and how Long Creek administrators applied them in this case are expected to be scrutinized for months. Michelle Knowles, who lives in North Vassalboro, has retained Augusta attorney Walter McKee, who said that while he cannot discuss the facts of the case until the various investigations are complete, the state’s care of Knowles appears deficient.

“Let’s be real here. This is a suicidal detainee in a juvenile facility. There’s no way somebody like that should ever be in a position to have the means to kill themselves,” McKee said. “On its face, it looks like there was a severe deficiency. Exactly what that deficiency was, how severe it was, remains to be seen.”

Knowles said that because her son – who was biologically female but identified as male from age 3 – was being detained pretrial and had not been committed to Long Creek by a judge, he was unable to access a level of care that more permanent residents may receive.

“Long Creek is a correctional facility,” said Christopher Northrop, a clinical professor at the University of Maine School of Law and director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic. “It is not a mental health treatment facility. It is not a substance-abuse treatment facility. Although there (are) more services and better education available on the committed side, it is still a correctional facility.”

There are no classifications of high-risk, medium-risk or low-risk detainees, he said. Staff members try to ensure that medications that were administered before detention continue, but in practice the transitions are not always smooth. And anyone who was receiving regular counseling or psychiatric care is typically cut off from that treatment, along with contact with family, friends and the community.

“You certainly become disconnected from your primary care physician, your counselors, and they do not have staff on site to provide those services,” said Northrop, who was describing the practices at the facility and offered no opinion on Knowles’ care. “And it is reasonably difficult to find someone in the community who is willing to come in and, if they are willing to come in, to facilitate that. Long Creek was not built for the health and safety and therapeutic needs of kids. It was built for public safety needs. It was built for kids who are a danger.”

That means that much of the mental health care within the facility is provided on an acute basis. When someone makes an attempt on his own life, psychiatric professionals are immediately dispatched. But addressing issues deeper than those presented in the present day are difficult, Northrop said.

“They Band-Aid it the best they can, but it is very temporary and often incomplete,” he said. “And again, I don’t think it’s because they’re not doing their job. It is because it is not a treatment facility. It is meant for something different.”

Yet Northrop estimated that about two-thirds of kids who managed to get to Long Creek have significant mental health needs.

Maisie began to show signs of mental health problems when he was 9, when Michelle noticed that he had begun to incessantly pick at the skin on his thumbs, a habit that increased whenever Michelle had to leave the house. Soon, Maisie was stealing safety pins and using them to hurt himself.

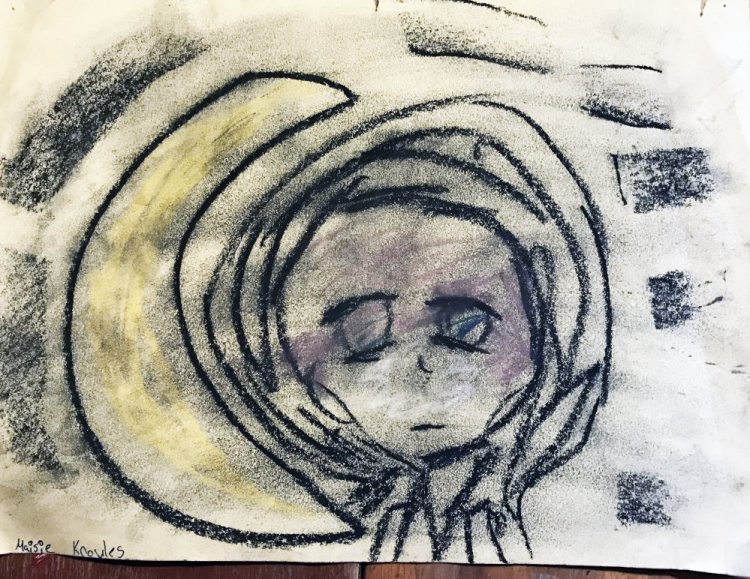

Even Maisie’s drawing habits changed, from bright, colorful pictures to depictions filled with black. A self-portrait from around that time shows a worried, morose face obscured by streaks of charcoal, ringed in layers of black.

EARLY SIGNS OF TROUBLE, RUN-INS WITH THE LAW

The first time Michelle had to seek mental health care for her son came one day when he was 9 or 10, after he went out to play in the woods. While alone among the trees behind their house, Maisie thought three men were chasing him through the brush. So terrified of being caught, he leapt from a precipice in a nearby gravel pit, spraining both ankles. When firefighters found him, he was buried up to his thighs and was struggling to break free.

But when police looked for evidence of the men, they found only one set of footprints.

The problems persisted, and diagnoses ranged from the more common depression and anxiety to the more serious borderline personality disorder, which made Maisie volatile and unpredictable around friends and doctors who were trying to help him. He at times reported hearing voices and was on medication to control his symptoms from an early age.

Through it all, Michelle Knowles always had a team of doctors and therapists around her son.

Maisie came into contact with the criminal justice system as a teenager. After experiencing a romantic rejection, he delivered a written bomb threat in September 2015 to Cony High School, triggering probation conditions and new scrutiny from the courts.

Then this past August, Michelle Knowles said her son set a small fire in his bedroom shortly before both of them left for a probation meeting. When they returned, smoke was pouring out of their modest mobile home. Michelle rushed in to try to put out the flames and was overcome by smoke. Miraculously, damage was contained and the house was largely unscathed.

Maisie was charged with felony arson, and a judge ordered him held at Long Creek.

Michelle said her son felt intense guilt about nearly killing her and that Long Creek staff never probed that issue.

In the midst of his incarceration, the teenager was also experiencing an imagined pregnancy and believed he had lost the baby.

“No one (at Long Creek) wanted to talk about it,” Knowles said. “What I got when I brought it up is: ‘We already know about that. We’re working on Long Creek forward, not Long Creek behind.'”

This apparent temporary approach to mental health care also raised serious concerns for Jason Szanyi, the deputy director of the Children’s Law and Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

“To say that we’re just going to focus on the day to day, if that means we’re not going to look at this young person’s history until they’re adjudicated, at which point we’ll take that stuff seriously, that’s absurd and irresponsible,” Szanyi said. “You have to be realistic about what you can accomplish in the way of longer-term therapy … and other forms of treatment, and to be sure, some of those take a long time and it takes a long time to establish a rapport with young people. But that does not mean that there’s no role for mental health professionals to ensure the safety of a young person with a history of trauma or self-harm.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story