Opponents of new national monuments in Maine’s North Woods and off coastal New England are asking whether Donald Trump could reverse those decisions as part of his campaign pledge to overturn President Obama’s executive orders.

Although preliminary, the discussions illustrate how Trump’s election is already affecting debate on conservation and environmental issues.

President-elect Trump vowed repeatedly during his campaign to repeal the Obama policies he viewed as executive overreach. Trump often made those comments in relation to issues such as immigration, foreign policy or environmental regulation.

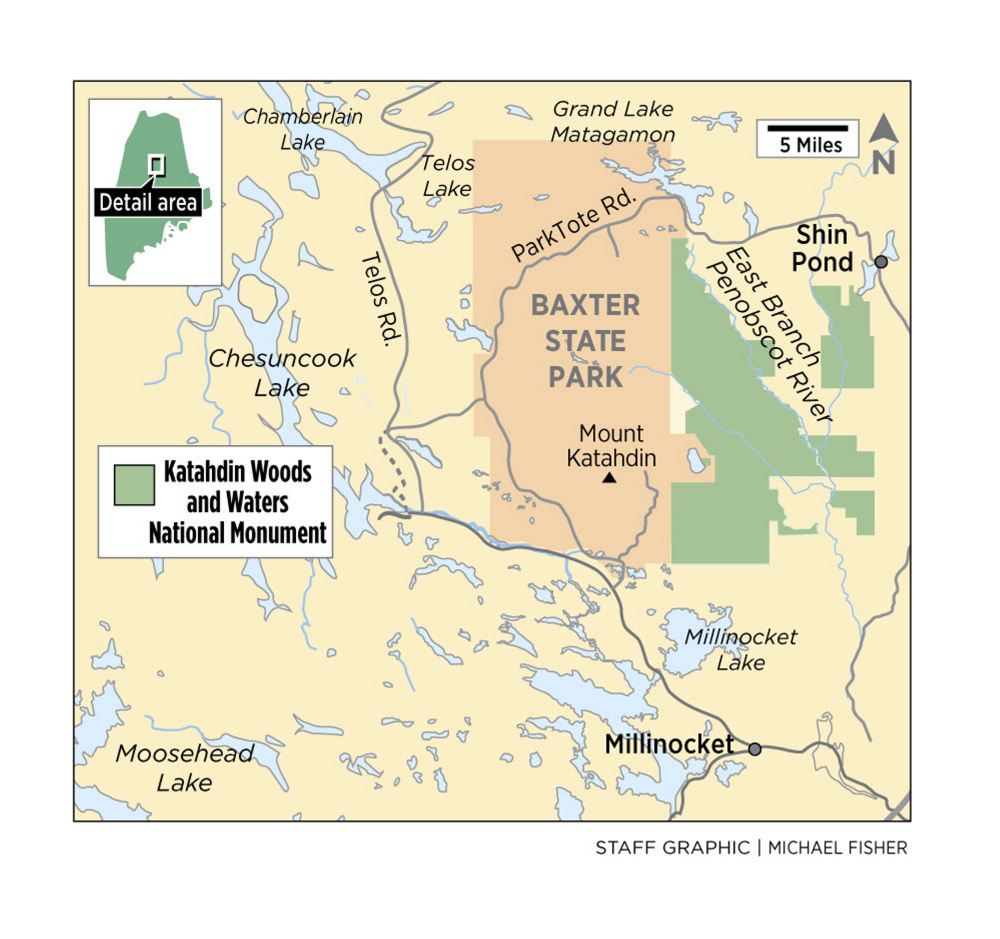

But several opponents of the 2-month-old Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument say they hope Trump could take steps to reverse an 87,500-acre designation they argue will hurt local communities or industries.

“I think it has crossed a lot of people’s minds,” said Anne Mitchell, president and chairwoman of the Maine Woods Coalition, an organization that fought the Katahdin-area monument designation. “The fact that Trump mentioned it when he was up here (campaigning) tells me somebody told him about it. … It’s certainly an interesting idea and one we would like to take a look at.”

However, no president has ever reversed a predecessor’s executive proclamation establishing a national monument. And some parks advocates question whether the law would allow it, even if a president tried.

“There are no examples of a president ever reversing a national monument designation since the law was passed over 100 years ago,” said Kristen Brengel, vice president of government affairs at the National Parks Conservation Association, a nonpartisan organization that advocates on behalf of national parks and public lands. “It has never happened before.”

Meanwhile, supporters of the new Katahdin-area national monument are concerned about the mere discussion. They hope Trump will leave alone Maine’s latest addition to the National Park Service and allow local communities to continue the work of incorporating the monument into the local economy.

“Even though winter is coming and there are no leaves on the trees, there are still people going in there to enjoy it,” said Marsha Donahue, owner of North Light Gallery in Millinocket and a vocal supporter of the monument.

The discussion isn’t limited to the North Woods national monument.

Fishermen opposed to Obama’s designation of nearly 5,000 square miles of underwater ecosystem off the coast of southern New England – known as the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument – also are exploring their options, whether through Trump or the Republican-controlled Congress.

“In the immediate aftermath of Donald Trump’s election, I would say there is a lot of talk about what can be done,” said Robert Vanasse, executive director of the National Coalition for Fishing Communities, which represents fishing organizations and businesses. Vanasse classified the discussions as “informal conversations,” but added: “Clearly the companies and fishermen that have been economically damaged by the actions of the Obama administration are thinking about what in this new (political) environment – president, House and Senate – might be possible.”

Obama designated Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument on Sept. 15, protecting an underwater mountain range that is home to many rare and endangered species.

“There is no authority for the revocation of a proclamation designating a national monument, no president has ever even attempted to do so, and the U.S. Attorney General issued a formal opinion that a president could not eliminate or terminate a monument established by previous presidential action,” said Sean Mahoney, director of the Conservation Law Foundation’s Maine advocacy center.

Obama created the 87,500-acre Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument on Aug. 24 after a years-long, often contentious debate over land conservation and economic development in the Katahdin region. A foundation created by conservationist and entrepreneur Roxanne Quimby donated the land just east of Baxter State Park to the National Park Service just days earlier.

Gov. Paul LePage and U.S. Rep. Bruce Poliquin – both Republicans – had strongly opposed the Katahdin region monument, and the issue had deeply divided the local community.

Trump railed against Obama’s creation of the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument during a campaign stop in Bangor on Oct. 15. Speaking to a fired-up crowd of more than 3,500, Trump accused Obama of making the designation with “no consideration” for local concerns, impacts on the forestry industry or opposition from lawmakers. Trump pledged that, under his administration “we’re going to protect the right of people and the people of Maine to use their own land.”

“Obama and (Hillary) Clinton don’t care that this area badly needs jobs and growth, and that this decision, done at the stroke of a pen without the support of the local community, undermines the people that live and work right here in Maine,” he said. “That’s a bad, bad bill. But we’re going to turn it all around. Believe me. America’s comeback begins on November 8th.”

Trump’s statement that he would “turn it all around” appeared aimed at reversing the overall direction of the country under Obama rather than the Katahdin-area national monument designation in particular. But conservation and environmental organizations already are bracing for potential attempts by a Trump administration to reverse course on some of the environmental initiatives pursued by Obama, to loosen regulations on businesses and to pull back U.S. involvement in international global warming pacts.

But it’s not clear whether a President Trump – or any other occupant of the Oval Office – could undo a predecessor’s actions creating a national monument. Although his action was denounced by critics, Obama was using powers granted to the president by Congress more than a century ago.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 allows presidents to designate national monuments through executive proclamations in order to quickly protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest” on federally owned land. National parks, by comparison, can only be created by Congress.

Presidents can – and have – modified national monuments created by their predecessors, often by elevating them to full national parks. Congress has the power to abolish national monuments and there have been several pushes in recent congressional sessions to roll back presidents’ sweeping authority under the Antiquities Act.

A 1938 U.S. Attorney General’s opinion suggests that presidents do not have the power to abolish established monuments, yet the issue has apparently never been litigated in a court.

“The Antiquities Act does not expressly authorize a president to abolish a national monument established by an earlier presidential proclamation, and no president has done so,” reads a September 2016 analysis of national monuments and the law conducted by the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan agency that provides policy and legal analysis to Congress. “There have been no court cases deciding the issue of the authority of the president to abolish a national monument.”

Mark Marston, an East Millinocket selectman who was a vocal opponent of the monument, has said he wants to work with the land’s new federal managers to ensure his community benefits from the monument. But Marston still regards the monument’s creation as an example of “backdoor politics,” given the local opposition and the lack of congressional involvement. And Marston said he is looking into the law.

“If a stroke of the pen can do this and (Trump) could undo it, I hope he would consider that,” Marston said.

Brengel, with the National Parks Conservation Association, said opponents need to think carefully about the ramifications of taking such a “destructive step” toward a monument that is already drawing interest.

“And in this case, you have deeded land from a private landowner, so you have some complexities with Katahdin Woods and Waters,” Brengel said. “But this would be unprecedented.”

As for Trump, Brengel said her organization is eager to talk to the president-elect about dedicating some of the $1 trillion he has proposed for infrastructure improvements toward the National Park System, which currently has a $12 billion maintenance backlog.

Donahue, the Millinocket art gallery owner, hopes the conversation about rescinding the Katahdin Woods and Waters’ national monument status will fade away.

“It’s very dear to me, so I don’t want to see it reversed,” Donahue said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story