NEW YORK — Got a live carp in your bathtub? Planning on losing a day to food prep for the October Jewish holidays?

We don’t think so, and neither do Jeffrey Yoskowitz and Liz Alpern.

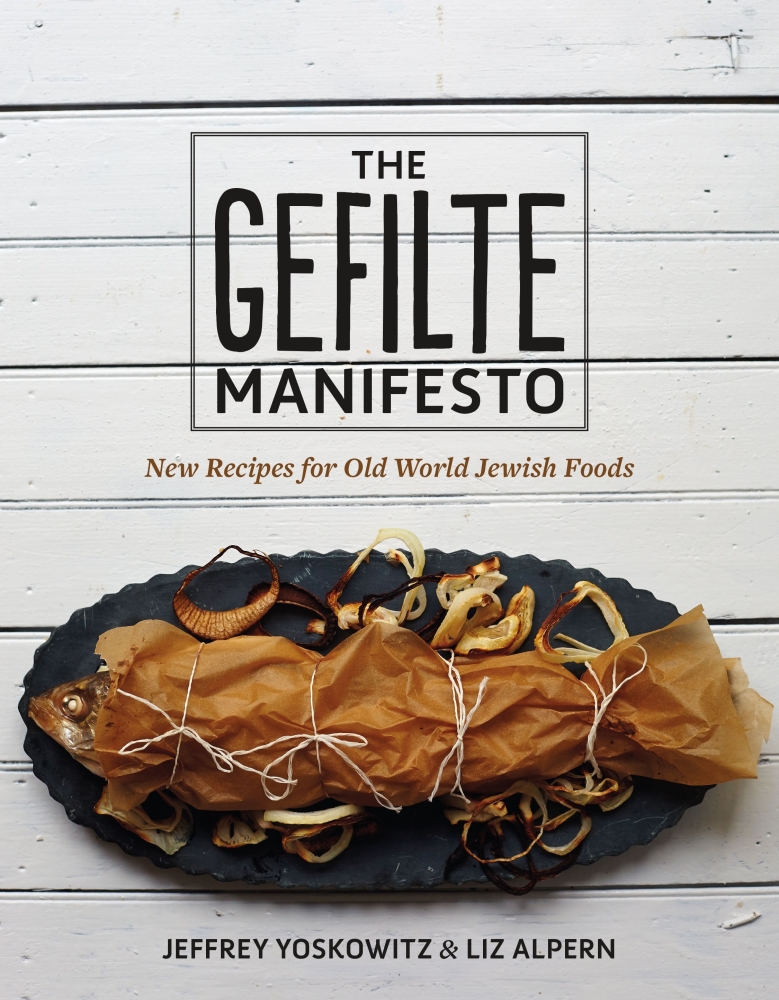

They’re the authors of a new cookbook, “The Gefilte Manifesto,” a lively collection of Ashkenazi standards – some with a twist and others left to wander back to the old country.

Out in September from Flatiron Books, the collection of history and recipes by the two young Brooklynites celebrates Jewish soul food from soup to nuts, kicking off with a bagel butter flecked with not one but two kinds of sesame seeds, black and white, and winding down with beverages, from beet and ginger kvass to a seeded rye cocktail.

As for the catchy title, there are three takes on gefilte fish, the fish food some people love to hate. That once included Alpern, who as part of her family’s Passover seders, declined the dish “every year of my life” growing up. It was the gelatinous jarred version, “and I hated it,” she said in a recent interview with Yoskowitz.

“Until I started making my own, I associated it with something I would never eat,” Alpern said of her upbringing in Long Beach, New York, just outside New York City.

Yoskowitz, from Basking Ridge, New Jersey, grew up with lots more love for gefilte fish. It was made by his grandmother, then she stopped and his family relied on a local shop, he said.

“But I didn’t like the horseradish. It was usually the beet horseradish,” Yoskowitz recalled. “But later, the moment I put horseradish on, I felt like an adult.”

In 2011, the two friends started making gefilte fish together, experimenting as they embraced its place in Ashkenazi lore, in both Europe and North America.

They wondered why nobody was making gefilte fish relevant again, putting the soul back in.

At its most basic, gefilte is made by mixing pulverized freshwater fish with eggs, onions and spices. Bread crumbs are often used today. It stood, especially on the Passover seder table, as a symbol of Ashkenazi resourcefulness, the two said. Exactly how far can a single fish be stretched to feed an entire family?

Usually served cold or at room temperature, there were practical aspects to gefilte fish. It’s often poached or baked, when it doesn’t come from a jar.

Lake fish is commonly used, including carp and pike. The two don’t use carp because, Yoskowitz said, it’s a bottom-feeding fish that tends to be high in heavy metals, especially when it comes from the Great Lakes.

“Most people commonly think of gefilte fish as a bunch of fish balls in a jar. That’s where the misconception is, that gefilte fish is gross and unappetizing,” he said.

Their recipes look anything but, often coming in terrine form, sliced and served with their colorful, grated horseradish relishes: A sweet beet version and a carrot-citrus version.

“What we realized right away was we need to make all of this look like something you’d want to eat,” Alpern said. “The first thing I would say to someone who is unfamiliar and maybe unwilling is you’ll see that this is a fish pate.”

Prep time for their gefilte dishes? Usually under an hour and a half, including baking, Yoskowitz said. No live carp in the tub needed. Just use fillets.

“We like to say that our gefilte fish tastes like gefilte fish,” Alpern said. “We’re not trying to add, you know, hot sauce or cumin to our gefilte fish.”

But there are twists, such as fresh herbs to add color and freshness.

In researching gefilte fish, which in Yiddish translates to “stuffed fish” (there’s a recipe for that, too) the two delved into what they describe as “the gefilte line.”

The line: Do you make your gefilte fish sweet or peppery?

In Galicia, or modern-day southern Poland, sugar beet factories were common and Polish Jews added sugar to everything, including gefilte, they said. North of Galicia, Lithuanians, Latvians and some Russians spiced gefilte fish with pepper.

And there was a third group: People who lived farther south of Galicia, in places that included Hungary, preferred not to spice their gefilte with anything at all.

The two compromised in the book with a couple of recipes that include both sweet and peppery flavors, but not much of either.

They also discovered that Lithuanian Jews, Hungarians and Galicians all agreed that horseradish relish, or chrain in Yiddish, is the only acceptable condiment to grace the top of gefilte.

Why? This Yiddish proverb speaks volumes: “Gefilte fish without chrain is punishment enough.”

SWEET LOKSHEN KUGEL WITH PLUMS

Here’s an update on another holiday tradition from “The Gefilte Manifesto” by Jeffrey Yoskowitz and Liz Alpern.

Serves 12

8 ounces egg noodles

1/2 cup (1 stick) unsalted butter, at room temperature, plus more for greasing the pan

8 cups small-curd cottage cheese

8 ounces cream cheese, cut into pieces, at room temperature

2 cups whole milk

1/4 cup sour cream

3 large eggs

1/2 cup pure maple syrup or granulated sugar

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

6 teaspoons ground cinnamon

6 tablespoons light brown sugar

About 11/2 pounds plums, pitted and sliced

Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil. Cook the noodles just until tender, about 5 minutes. Drain and transfer to a bowl. Add the butter and stir gently to coat the noodles. Set aside.

In a large bowl with high sides, whisk together the cottage cheese and cream cheese until fluffy. (Alternatively, use a hand mixer.) One at a time, add the milk, sour cream, eggs, maple syrup or sugar, and vanilla, whisking to incorporate after adding each ingredient.

Add the cottage cheese mixture to the bowl with the egg noodles and gently combine. Pour the mixture into a greased 9 x 13 inch baking pan. Cover the pan and refrigerate for at least 1 hour and up to overnight.

Preheat the oven to 350 F. Bake the kugel, uncovered, for 45 minutes, then top decoratively with the plums and sprinkle with the cinnamon and brown sugar. Bake for 30 minutes more, until the fruit has softened and released its juices. Remove from the oven and let sit for at least 30 minutes before slicing and serving. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story