John Craighead, a lifelong outdoorsman who along with his twin brother subdued, tagged and tracked the grizzly bears of Yellowstone National Park in a landmark study during the 1960s, revealing as never before the lives of those mighty, mysterious animals, died Sept. 18 at his home in Missoula, Montana. He was 100.

A son, Derek Craighead, confirmed the death and said he did not know the cause.

From the earliest days of their boyhood, Craighead and his twin, Frank Jr., felt a pull toward nature that would tug at them all their lives. It took them from Washington, D.C., where they explored the banks of the Potomac River with their entomologist father, to rugged regions of Wyoming and Montana, where they established themselves as preeminent conservationists.

The brothers were credited with helping write the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, legislation that protects 208 rivers in 40 states. They were regular contributors to National Geographic magazine, once chronicling their sojourn in India as guests of the brother of a maharaja, who shared their enthusiasm for falconry.

But they were best known for their study of grizzlies begun in 1959 – an initiative that sparked an angry confrontation with Yellowstone officials but that yielded a wealth of information about the park’s grizzlies at a time when they came perilously close to extinction.

When the brothers embarked on their project, “the usual ‘communication’ between man and grizzly,” they observed, was “through a rifle bullet.” They sought what they described as a “rendezvous with grizzlies in their most intimate moments.”

The nature writer Thomas McNamee, an authority on grizzlies, has credited the Craigheads with making “possible the first penetration of human light through the ancient opacity of bearhood.” In an interview, he said that “John and Frank Craighead were the greatest pioneers of modern wildlife study by far.”

The brothers perfected techniques of tranquilizing grizzlies so that they could be outfitted with radio collars, an innovation at the time. They then followed the bears in their wanderings – even into their dens – and discovered that grizzlies were far more social than previously thought.

“Within a few years on all kinds of animals all over the world, scientists were placing radios,” Craighead once told a publication of the University of Montana, where he taught for years.

The brothers discovered that they could determine a bear’s age by analyzing its teeth. They learned that bears mated for the first time between the ages of 4 and 7, not earlier in life, as scientists previously believed. Only 60 percent of grizzlies live longer than 18 months, they found, and the average life span was five or six years. One observation was particularly poignant: Female grizzlies adopted orphan cubs.

The brothers followed bears for up to 40 hours at a time, even wading through frigid streams to avoid losing their trail.

Despite the dangers they presented, grizzlies had long been a chief draw for visitors to Yellowstone. For years, the bears were permitted to feed on the food waste of the park’s lodges. Tourists observed the spectacle from stands erected around the dumps, according to an account in National Geographic by science writer David Quammen.

In 1968, Yellowstone officials abruptly closed the dumps in an effort to force the bears into a more natural diet and lifestyle. The decision sparked a “war between the Craigheads and the Park Service,” McNamee said, with the Craigheads arguing that the bears – by then accustomed to human food – would starve if the park did not artificially feed them while phasing in the new plan.

The Craigheads’ fears proved prescient. After the dumps closed, hungry grizzlies began seeking food in campgrounds and other inhabited areas, forcing officials to kill or remove them. The grizzly population declined so dramatically that, by 1971, the Craigheads publicly warned that the Yellowstone population might be eliminated.

In time, McNamee said, the remaining bears relearned how to forage and hunt in their natural habitat. The population of grizzlies in the area known as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem rebounded from 136 in 1975, when the grizzlies were designated a threatened species, to roughly 700 today, according to park estimates.

In 2007, The Washington Post described the grizzlies’ resurgence as a “direct ripple effect” of the Craigheads’ research. The Audubon Society recognized the brothers as among the 100 most significant figures in 20th-century conservation.

John Johnson Craighead, along with his brother, Frank, was born in Washington on Aug. 14, 1916. Their sister was Jean Craighead George, the noted author of young-adult books including “My Side of the Mountain” and “Julie of the Wolves.”

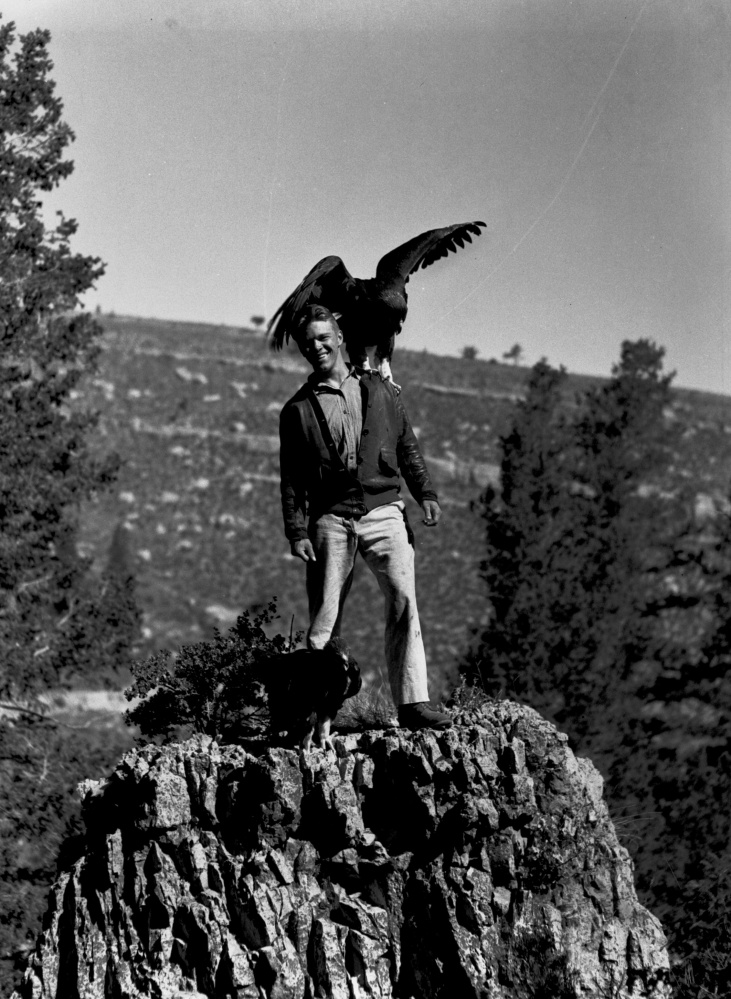

After graduating in 1935 from Western High School, the twins took a trip west, photographing hawks and falcons. “The day our ’28 Chevy topped this hill in Wyoming and we spotted the Tetons, it was like our souls got sucked right into the Rocky Mountains,” John Craighead once told an interviewer. “We knew right then and there that our calling was out West.”

The brothers later co-authored the volume “Hawks in the Hand: Adventures in Photography and Falconry” (1939).

They received science degrees in 1939 from what was then Pennsylvania State College. The following year, they received master’s degrees in ecology and wildlife management from the University of Michigan.

During World War II, the Craigheads created a survival course for naval aviators and wrote the guide “How to Survive on Land and Sea.” They returned to the University of Michigan, where both received PhDs in 1950. Soon after, John Craighead joined the University of Montana, where he led the Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit.

Survivors include his wife of 70 years, the former Margaret “Cony” Smith of Missoula; three children, Karen Haynam of Moose, Wyoming, Derek Craighead of Kelly, Wyoming, and John Craighead of Missoula; and five grandchildren. Frank Craighead Jr. died in 2001.

Craighead once explained his fascination with the grizzly, an animal loved and feared, threatening and majestic.

“If we can’t get along with the grizzly,” Craighead once said, “it makes me less hopeful we’ll be able to get along with each other.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story